만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년의 학교 건강관리에 대한 인식: 통합적 문헌고찰

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this integrative review was to synthesize previous research on perceptions of school health care among school-aged children and adolescents with chronic diseases.

Methods

This study was performed in accordance with Whittemore and Knafl's stages of an integrative review (problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation of the results). Four databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and Web of Science) were used to retrieve relevant articles.

Results

Eighteen articles were included in this review. We identified five thematic categories: peer-related issues, a safe school environment, self-perception of an existing disease, self-management, and a supportive school environment.

Conclusion

It is necessary to establish a school health care system with a supportive environment for children and adolescents with chronic diseases.

Key words: 아동; 청소년; 자기관리; 만성질환; 학교

Key words: Child; Adolescent; Self-management; Chronic disease; Schools

서 론

1. 연구의 필요성

의학기술의 발달로 인해 조기발견이 가능해지고, 환경과 생활 양식의 변화가 진행되면서 당뇨병, 천식, 아토피 피부염, 소아암 등 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 및 청소년의 수가 증가하고 있다. 국내 아동의 당뇨병 유병률은 2015년 5,338명으로 매년 5.6%의 증가를 보이고 있으며[ 1], 10만 명당 3.19명의 아동이 당뇨병에 이환되는 것으로 알려져 있다[ 2]. 2016년 국민보험공단 통계에 따르면, 천식과 아토피 피부염으로 진료 받은 12세 아동은 각각 528천명, 474천명으로 천식 진단 대상자의 35%, 아토피 피부염 진단 대상자의 48.6%가 12세 이하 아동이다[ 3]. 소아암 역시 국내 연간 1,000명 이상의 아동이 새롭게 암으로 진단받고 있으며, 이는 10만 명당 매년 약 14.3명에 해당한다[ 4]. 이러한 만성질환을 가진 아동의 성인까지의 생존율은 90% 이상이지만, 만성질환으로 인한 증상 이외에 투약과 치료과정과 관련하여 성장과 발달 지연, 사회적 고립 및 정신심리문제 발현의 위험이 있다[ 5]. 만성질환을 가진 아동은 학교 생활을 하는 데에 질병이 없는 아동과 비교해 자존감과 행복지수가 낮으며[ 6, 7], 우울, 불안, 위험 행동, 사회적 고립 등 심리적 문제[ 8] 및 자살 충동[ 9]을 일으키기도 쉽다. 또한 만성질환 청소년은 만성질환이 없는 청소년보다 학교에서의 따돌림 경험이 빈번한 것으로 보고되고 있다[ 10]. 이러한 심리적 고충은 학교에서 대부분의 시간을 보내는 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 및 청소년의 자기조절 능력 및 건강관리 행위와 직결되는 부분이다[ 11]. 이러한 만성질환 아동 및 청소년의 안녕을 위해 자율감, 자신감, 타인과의 관계성[ 12] 외에 학교에서의 지지를 포함한 사회적 지지가 중요한 것으로 나타났다[ 13]. 무엇보다 학령기 아동 및 청소년이 낮 동안의 대부분의 시간을 학교에서 보내기 때문에 학교에서의 경험은 만성질환 아동의 질병관리에 중요하다고 할 수 있다[ 14]. 그러나 학교가 만성질환 아동에게는 하나의 큰 스트레스원이 되기도 하며[ 15], 학교기능과 관련하여 낮은 삶의 질을 보고하는 연구도 있다[ 16]. 만성질환 아동의 증가 추세와 만성질환 아동 부모의 요구와 보건교사의 인슐린 주사법안, 응급상황에서 보건교사의 글루카곤 및 에피펜 주사 법안이 제안되는 등 만성질환에 대한 학교건강관리에 대한 사회적 요구가 증가하고 있다[ 17]. 이와 같이 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 및 청소년에 대해 증가하는 건강요구에 따라 아동 및 청소년 중심의 학교건강관리가 필요하지만, 아동과 청소년이 인식하는 학교 건강관리에 대한 고찰 및 중재 프로그램에 대한 연구는 제한적이다. 따라서 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 및 청소년의 인식이 반영된 효과적인 중재 프로그램 개발이 절실하다. 이에 본 연구는 만성질환을 가진 아동 및 청소년의 요구 및 인식을 반영하는 학교 건강관리 프로그램 개발을 위한 기초자료로써 만성 질환을 가진 아동과 청소년의 학교 건강관리에 대한 인식을 통합적으로 고찰하고자 한다.

2. 연구 목적

본 연구의 목적은 학교 건강관리에 대한 만성질환 아동 ․ 청소년의 인식을 선행 연구의 통합적 고찰을 통해 분석함으로써, 만성질환을 가진 아동 및 청소년을 위한 학교 프로그램 개발의 기초자료를 제공하고자 함이다.

목적은 학교 건강관리에 대한 만성질환 아동 ․ 청소년의 인식을 선행 연구의 통합적 고찰을 통해 분석함으로써, 만성질환을 가진 아동 및 청소년을 위한 학교 프로그램 개발의 기초자료를 제공하고자 함이다.

연구 방법

1. 연구 절차

본 연구는 Whittemore와 Knafl [ 18]이 제시한 통합적 문헌고찰의 5단계인 문제인식, 문헌검색, 자료평가, 자료 분석, 자료제시의 5단계로 수행하였다. 첫 번째 단계는 문제인식을 통하여 연구자가 고찰하고자 하는 현상과 연구의 목적을 분명하게 나타나도록 하는것이다. 두 번째 단계는 선정한 주제에 적합한 모든 자료를 단계적으로 찾아내는 문헌검색 단계이다. 세 번째 단계는 자료 평가 단계로 연구의 질 평가 도구를 사용하여 선정한 논문에 대한 질 평가를 수행하였다. 네 번째 단계는 자료 분석 단계로 본 연구에서 도출된 질문에 따라 기존의 원 자료를 편견없이 분석하고, 의미를 종합하는 과정을 거쳤다. 다섯 번째 단계는 자료 제시 단계로 분석한 자료를 표로 제시하였다.

1) 1단계: 문제 인식

첫 번째 단계는 연구자가 고찰하고자 하는 현상과 연구의 목적을 분명하게 나타내기 위한 문제인식 단계로, 연구 문제는 ‘만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년이 인식하는 학교 건강관리의 속성은 무엇 인가?’이다. 선행문헌에 만성질환은 “chronic disease”, “chronic condition”, “chronic illness”로 사용되며, 1년에 1회 이상 병원방문을 포함하여 예방접종이나 투약으로 완치되거나 사라지지 않는 건강문제를 의미한다[ 19]. 교사와 보조교사에 의한 케어를 받고 있는 도움반 학생은 제외하고 보건교사에 의해 요양호 아동(만성질환을 가지고 있거나 신체가 허약해 학교교육 활동 중 건강상 문제가 발생할 가능성이 있어 특별한 주의가 필요한 아동[ 20]으로 관리 되고 있는 아동)을 포함하고자 하였다. 본 연구에서 만성질환 학령기 아동 및 청소년이란 천식, 당뇨 및 선천성 심질환, 혈액성 질환 등으로 진단받고 정기적 병원진료, 투약(기관지 확장제, 인슐린, 이뇨제 등) 및 자가조절을 필요로 하며, 초, 중, 고교의 일반 학급에 재학 중인 아동으로 만 6세 이상 18세 이하의 연령 범위로 정의하였다.

2) 2단계: 문헌검색

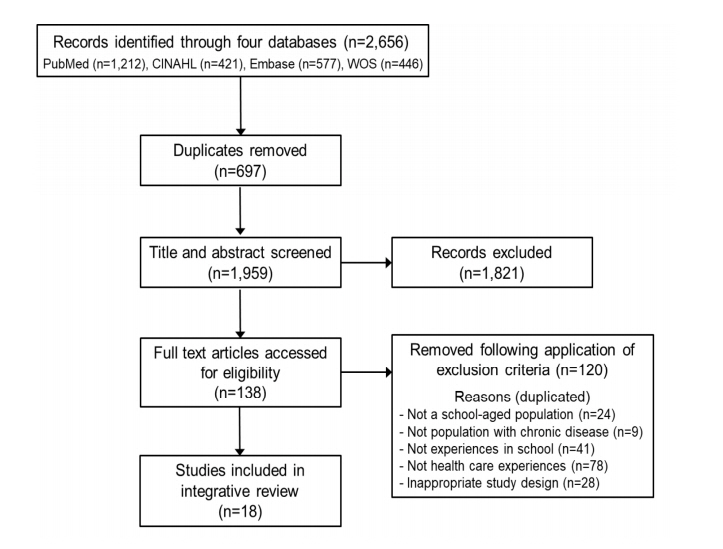

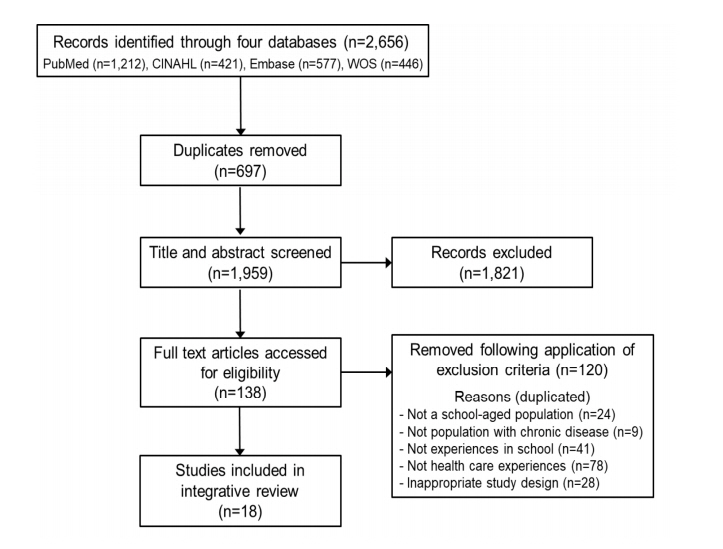

연구 목적에 맞는 문헌고찰을 위해 만성질환(chronic disease), 아동과 청소년(child and adolescent), 인식(perception), 학교(school)에 대한 4개의 핵심용어와 유사어를 이용하였으며( Table 1), 검색하는 논문의 출판연도는 지난 10년간의 인식을 알기 위해 2008년부터 2018년 11월까지 발표된 논문을 대상으로 하였다. 검색 당시 국내 데이터베이스 RISS, KISS, NDSL에서 검색된 연구는 0건 이었으며, 국외 데이터베이스는 PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, Web of Science (WOS)를 이용하여 고찰하였다. 문헌의 선정기준과 제외기준은 다음과 같다. 선정기준은 1) 영어로 작성된 논문, 2) 동료심사를 거친 학술지 논문, 3) 만성질환을 가진 아동 및 청소년을 대상으로 학교 건강관리에 대한 인식이나 경험을 조사한 논문, 4) 출판 중 논문이다. 제외기준은 1) 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년 이외의 연령을 대상으로 한 연구, 2) 만성 질환을 가진 아동 대상자가 아닌 논문, 3) 학교 건강관리 경험이 아닌 연구, 4) 입원한 아동, 의료기기 의존이 필요하거나 신체적 장애를 가진 아동을 대상으로 한 논문, 5) 석 ․ 박사 학위논문, 편집자 편지, 학술대회 발표논문, 6) 서술적 연구, 고찰연구, 중재 연구로 하였다. 검색된 문헌은 선정 및 제외기준에 따라 선택하였고, PRISMA flow diagram [ 21]을 작성하였으며, 서지 프로그램인 EndNote를 활용하였다. 두명의 연구자가 총 2,656개의 문헌을 검색하였고, 중복된 문헌 697개를 제외하고 1,959개 논문의 제목과 초록을 고찰하였다. 기준에 부합하는 138개 논문의 본문을 확인하였고, 학령기가 아닌 경우(n=24), 만성질환이 아닌 경우(n=9), 학교에서의 인식이 아닌 경우(n=41), 건강관리에 대한 인식이 아닌 경우(n=78), 연구 설계가 조사나 탐색연구가 아닌 경우(n=28)를 제외하고 주제와 적합한 18개 논문이 최종 선택되었다( Figure 1).

3) 3단계: 자료 평가

선행된 질적연구와 양적연구의 타당도를 결정하기 위해 비평적 평가를 시행하였다. 질적연구는 Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI)의 질적연구에 대한 비평적 평가 점검표를, 양적연구는 횡단적 단면 연구를 위한 양적연구에 대한 비평적 평가 점검표를 각각 적용하여 평가하였다[ 22]. 연구자 2명이 독립적으로 질 평가 체크리스트(질적연구 평가 10개 항목, 양적연구 평가 8개 항목, 혼합연구는 질적연구 평가와 양적연구 평가의 모든 항목인 18개 항목)를 작성하였다. 질 평가를 실시한 결과, 108항목 중 6항목이 일치하지 않아(연구자 간 질 평가 일치율 94.4%), 불일치가 되는 항목(양적연구 3편에서 연구자의 문화적 또는 이론적 진술, 연구자에 대한 연구의 영향 등)에 대해서는 서로 충분한 논의를 거친 후 합의를 하였다. 선정한 18편의 논문 모두 질 평가 기준을 충족하였다.

4) 4단계: 자료 분석

선정한 논문으로부터 자료를 추출하고 합성하기 위해 구조화된 자료 추출 형식을 엑셀 파일의 시트를 이용하여 연구자, 연구 설계, 대상자의 질환, 연구 목적, 사용한 측정도구, 국가, 대상자 수, 대상자 연령, 주요결과 등을 연대기적으로 기술하였다. 연구자 간 코딩한 자료에 대해 주제와 하위주제를 도출하기 위해 메모를 활용하였으며, 정기적인 전자메일 교신과 연구 모임을 통한 수시 회의를 통해 논문의 핵심결과, 주제 및 하위주제 합성에 대한 비교와 대조를 반복하여 합의를 도출하였다.

5) 5단계: 자료 제시

두 연구자가 연구결과를 반복적으로 읽으며 변수와 주제 간 관계성을 확인하고 표와 차트를 이용하여 자료를 제시하여 주제의 패턴을 확인하였다. 패턴 확인을 위해 집락화, 대조와 비교, 부분과 전체, 공통성·특이성을 분석하였다. 저자 간 패턴에 대한 합의를 이룬 후 주제와 하위주제를 도출하였다. 주제와 하위주제 관계에 대한 적절성과 주제의 하위주제에 대한 포괄성을 확인하였다. 통찰력을 통해 주제와 하위주제가 원 자료를 타당하게 제시하였는지 재검토하고 결론을 도출하였다.

연구 결과

1. 연구 대상 논문의 특성

만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년이 인식하는 학교 건강 관리 연구 총 18편의 특성을 분석한 결과는 Table 2와 같다. 연구가 진행된 국가는 미국이 9편(50.0%)으로 가장 많았고, 그 외 대만, 스웨덴, 브라질, 스페인, 영국에서 발표되었다. 연구 설계를 살펴보면, 양적연구가 9편(50.0%), 질적연구가 8편(44.4%), 혼합연구가 1편(5.6%)이었다. 대상 아동 및 청소년의 만성질환의 종류로는 1형 당뇨병 아동의 인식에 대한 연구가 11편(61.1%)으로 가장 많았으며, 천식 4편(22.2%), 다양한 질환을 포함한 경우가 2편(11.1%), 혈액성 질환(sickle cell disease)이 1편(5.6%)이었다.

2. 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년이 인식하는 학교 건강관리의 속성

만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년이 인식하는 학교 건강관리의 속성은 교우와의 관계(peer-related issues), 안전한 학교환경(safe school environment), 질병 인식(self-perception of an existing disease), 자가간호(self-management), 지지적 학교환경(supportive school environment) 다섯가지 주제로 도출되었다( Table 3).

1) 교우와의 관계

만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년의 학교 건강관리에 대한 인식으로는 교우와의 관계가 속성으로 확인되었다. 교우의 긍정적 역할은 5편( Appendix 1. 1-3,13,18)에서 확인되었고, 교우의 부정적인 역할은 7편( Appendix 1. 1-4,14,15,18)에서 확인되었다. 교우관계에 대한 대처는 1편( Appendix 1. 9)의 연구에서 확인되었다. 교우가 아동 및 청소년이 앓는 만성질환에 대해 관심을 가져 주고 공감하는 것이 학교생활 경험을 긍정적으로 인식하는 데에 촉진요인이 되기도 하였다. 그러나 교우가 자신의 만성질환에 대한 호기심을 갖는 것에 두려움을 지니고, 교우와의 의사소통에 어려움을 인식하기도 하였다. 교우와 더 편안한 관계를 지속하기 위한 방법을 스스로 모색하기도 하였다.

2) 안전한 학교환경

만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년의 학교 건강관리에 대한 인식의 속성으로는 안전한 학교환경이 확인되었다. 안전한 학교환경은 물리적 보호를 위한 구조적 환경조성을 의미한다[ 14]. 안전하고 편리한 투약과 검사를 위한 환경이 마련되어야 한다는 연구 2편( Appendix 1. 5,6)과 응급상황에 대처할 수 있어야 한다는 연구 1편( Appendix 1. 15)이 있었다. 만성질환 관리를 위한 약물 투여는 학교의 사무실이나 구내식당에서 수행되었다. 투약을 위한 접근성이 제한되어 있음을 인식하였고, 투약하기가 불편함을 토로하기도 하였다. 학교에서 보건교사의 역할을 인식한 연구는 6편( Appendix 1. 2,9,11,12,16,17)이었으며, 보건교사의 역할에 대해 긍정적으로 또는 부정적으로 인식하기도 하였다. 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년은 교사의 질환에 대한 지식부족으로 인해 자신이 비효과적 자가관리를 할 수도 있으므로, 교사의 교육과 훈련의 중요성에 대해 보고하였다. 교사 교육 및 훈련에 대한 연구는 4편( Appendix 1. 4,5,15,18)이 확인되었다. 또한, 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년은 학교직원 간 정보공유와 역할분담이 불충분하기 때문에 학교 기반 건강관리가 효율적으로 이루어지기 어렵다고 여겼다. 학교직원 간 정보공유와 역할분담에 대한 연구는 3편( Appendix 1. 4,7,18)이었다. 더불어, 질병에 대한 행정적 지원에 대해서는 2편( Appendix 1. 3,15)의 연구에서 확인되었다. 즉, 교사가 건강문제를 발견하고 보건교사에게 인계하고, 부모에게 연락하는 절차에 대해 명확히 하는 것이 요구되며, 문서화된 정보 제공이 유용하다고 하였다.

3) 질병 인식

만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년은 자신의 질환에 대해 스스로 인식하고 있었다. 질병으로 인한 증상과 합병증을 경험한다는 연구는 5편( Appendix 1. 5-7,15,18)이었으며, 그로 인한 두려움과 같은 부정적 감정을 경험한다는 연구는 1편( Appendix 1. 16)있었다. 질병으로 인한 고충에 대한 연구는 6편( Appendix 1. 2,3,6,9,13,15)이었다. 질병으로 인한 고충으로 학교생활에 어려움을 느끼거나 자가관리를 어떻게 할지 걱정하였다. 또한, 질병과 약물 투여에 대한 타인의 부정적인 느낌과 교우들과 자신이 다름을 인식하였다. 질병관리를 촉진하는 요인은 자신이 정상이라는 인식이며, 반대로 자신이 정상이 아니라는 인식은 질병관리의 장애물이 된다고 하였다. 그렇기 때문에 교우들과 다르지 않기 위해 스스로 노력하였다.

4) 자가간호

만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년의 학교 건강관리에 대한 인식의 다음 속성으로는 자가간호가 확인되었다. 자가간호의 수행의 중요성을 인식한 연구는 3편( Appendix 1. 8,9,18)이었으며, 특히 약물 투여의 중요성을 인식하였다. 그러나 기억하지 못하는 것과 사회적 우선순위는 투약이행을 방해하였고, 투약이행을 촉진하였으며, 고칼로리 음식에 대한 유혹이 자가간호에 영향을 미치는 등 자가간호에 미치는 요인을 인식하였다( Appendix 1. 8,9,14). 학교에 식사를 준비해 가야 하는 경우도 발생하였다. 자가관리 수행에 대한 연구는 4편( Appendix 1. 2,3,6,13)이었다. 실제 자가관리를 수행하기 위해 질환에 대한 관리방법을 배우고, 질병조절과 증상 발생을 예방하기 위한 방법을 강구하였다.

5) 지지적 학교환경

만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년의 학교 건강관리에 대한 인식의 마지막 속성은 지지적 학교환경이었다. 지지적 학교환경은 학교의 구성원, 즉 교사나 학우의 인식개선을 통해 차별하지 않고, 옹호하는 사회적 지지를 의미한다[ 14]. 학교로부터의 지지는 아동의 자가간호 행동과 삶의 만족도에 긍정적으로 영향을 미쳤다. 교사, 학우로부터의 지지에 대한 연구는 10편( Appendix 1. 2-5,10,12,14-16,18)이었다. 교사 및 학우로부터의 지지는 천식 관리를 촉진하며, 반대의 경우는 천식관리의 장애가 되었다. 질병으로 인한 차별을 경험하는 연구는 1편( Appendix 1. 14)이었으며, 프라이버시와 관련한 연구도 1편( Appendix 1. 18) 있었다. 투약과정에서 프라이버시를 유지하는 것이 중요하다고 인식하였다. 충분한 학습 기회에 대한 연구는 2편( Appendix 1. 3,16)이 있었다. 충분한 학습 기회란 결석으로 인한 학습 결손에 대해 동일한 학습 기회 즉 학습 보충과 방과 후 활동 중 지지에 대한 요구를 포함하였다.

논 의

본 연구는 통합적 문헌고찰을 사용하여 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년이 인식하는 학교 건강관리의 필수적 속성을 파악하기 위해 시행되었으며, 이후 수행되는 학교보건 프로그램 개발에 대한 요구도 조사의 근거자료로 유용성이 있다. 본 연구에서는 최종 선정된 18개의 국외 연구를 통합적으로 고찰하여 논문의 특성을 분석하고, 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년이 인식하는 학교 건강관리의 속성을 도출하였다.

만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년이 인식하는 학교 건강 관리 연구의 특성을 살펴보면, 본 연구에서 선정한 18편의 연구 중 50.0%가 미국, 22.2%가 대만에서 이루어져 관심 주제에 대해 일부 및 소수의 국가에서 연구를 진행해 왔음을 확인할 수 있었다. 대상아동이 가진 만성질환의 종류로는 1형 당뇨병 11편, 천식 4편이었다. 이는 학교 건강관리가 유병률이 높은 아동의 주요 만성질환에 초점을 두고 있음을 알 수 있다. 좀 더 다양한 국가에서 다양한 만성 질환을 가진 학령기 아동 및 청소년의 학교 건강관리 인식에 대한 연구가 이루어질 필요가 있다. 향후 국내에서도 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년의 학교 건강관리 인식 및 요구에 대한 연구와 프로그램 개발 연구 수행이 요구된다. 본 연구에 포함된 논문의 학령기 아동과 청소년의 연령 범위는 6편의 경우 학령기, 학령기 일부 및 고등학생에 국한하여 이루어졌으며, 12편의 연구는 다양한 발달단계(학령기부터 중학생 또는 고등학생까지)를 포함하였다. 연령 범위가 넓은 반면, 다양한 발달단계에 있는 학령기 아동 및 청소년의 인식을 알 수 있었다.

연구 결과 밝혀진 각각의 속성을 중심으로 논의하면서 추후 학교보건 프로그램 개발 방향을 모색하고자 한다. 국내 만성질환 아동 및 청소년을 위한 학교건강관리에 대한 실태는 제한적이지만, 국내 보건교사는 요양호자 관리를 수행하고 있으며, 응급처치, 보건생활지도 등의 업무를 수행하고 있다[ 20]. 본 연구에서 만성질환 아동의 학교건강관리에서의 첫 번째 인식은 교우와의 관계였다. 만성질환 아동의 교우관계 및 교우관계 개선을 위한 학교에서의 노력에 대한 연구가 국내에서는 없는 실정이다. 안전사고, 금연교실, 약물 오남용 예방, 성희롱 ․ 성폭력 예방 이외 만성질환 아동에 대한 교우관계 개선을 위한 프로그램 운영이 필요하다. 가령, 질병이 없는 학생이 당뇨나 천식에 대해 올바르게 인식할 수 있는 교육자료 개발과 이러한 자료를 이용한 교사 및 보건교사의 학생지도가 필요하다. 또한, 이 속성은 특히 만성질환을 가진 아동이 실제 학교에서 생활하면서 경험하게 되는 측면과 관련되므로 부모 또는 보건교사의 인식과는 차별점이 될 수 있다. 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 및 청소년은 교우와의 관계에서 긍정적인 측면과 부정적인 측면에 대한 인식이 질환을 가지지 않은 일반 학령기 아동 및 청소년에 비교해 더 구체적임을 알 수 있었다. 교우와의 관계는 교우들이 만성질환 관리에 대해 관심을 가지고 공감하는 긍정적 측면도 있었고, 만성질환 관리에 대해 부정적인 말을 하고, 따돌리거나 조롱하며, 고립시키고, 괴롭히는 부정적 측면도 있었다. 그러나 본 연구에서 교우와의 관계의 부정적인 측면뿐만 아니라 긍정적인 측면이 도출된 것이 괄목할 만하다. 일반 아동 및 청소년은 만성질환에 대한 인식이 부족할 수 있으므로, 이들을 대상으로 한 만성질환 교육은 질병에 대한 전반적 지식과 태도를 변화시킬 수 있다[ 23]. 교우는 만성질환 아동에게 특별한 존재이다. 교우는 1형 당뇨병 아동의 상태를 관찰하고 당뇨관리를 촉진시키거나 조력하며, 운동이나 식사 시간 동안 당뇨병 아동의 관리를 기다리며 일상생활을 함께 한다[ 24]. 교우와의 상호작용과 사회적 지지를 돕는 훈련은 청소년의 당화혈색소를 감소시키고, 자존감과 사회적 지지에 대한 지각 수준 및 질병에 대한 지식 향상에 도움이 되기도 한다[ 25]. 이와 같이 교우들이 질병관리를 돕는 측면을 강화하는 것은 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년을 위한 학교보건 프로그램 개발에 포함되어야 할 중요한 요소가 될 것이다. 두 번째로 밝혀진 속성은 ‘안전한 학교환경’이다. 아동의 성공적인 만성질환 관리를 위해 학교 직원을 대상으로 교육 중재를 제공하는 것이 도움이 될 수 있는데, 예로 직원의 건강관리 준비도가 높거나 훈련을 많이 받은 경우 그렇지 않은 학교에 비해 천식 관리 규정에 대한 이행도가 높고, 문서화된 천식 규정을 적용하여 보다 적극적으로 중재를 수행하여 그 결과 자가관리를 효율적으로 할 수 있었다[ 26]. 그러나 이러한 국외의 학교직원을 위한 교육 중재 프로그램의 운영을 포함하는 학교 건강관리 체계는 다양한 법적 기반을 갖추고 있지만, 국내의 경우는 만성질환 아동 관리에 대한 요구가 증가하고 있으나, 만성질환 아동의 학교 건강관리에 대한 업무는 보건교사에게 그 역할이 전적으로 치중되어 있으며 적절한 지원이 부재한 실정이다[ 17]. 특히, 국내 보건교사의 역할은 다른 나라의 보건교사의 역할 권한과 다르고[ 27], 만성질환 아동의 인슐린이나 천식약물과 같은 투약은 현재 보건교사의 도움을 받을 수 없으며, 이러한 문제는 국내 학교보건법에 명시된 보건교사의 역할범위가 제한적인 것과 관련된다[ 28]. 만성질환을 가진 아동이 보다 더 편리하고 안전한 돌봄을 받을 수 있는 시설과 행정적 체계, 학교직원과 교사의 만성질환 아동 관리 훈련, 응급상황 관리체계, 학교직원의 업무분담과 원활한 의사소통을 위한 법적 ․ 제도적 장치 등의 정책적 지원이 필수적이다. 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년이 인식하는 학교 건강 관리의 세 번째 속성은 ‘질병 인식’이다. 대상 학령기 아동 및 청소년은 만성질환으로 인한 증상과 합병증을 겪고, 질병과 증상으로 인한 걱정, 두려움, 슬픔 등 부정적인 감정을 갖고 있었다. 1형 당뇨병 아동의 우울과 같은 심리적 문제에 대해 지속적인 관심과 지지가 필요하다[ 27]. 증상과 합병증 관리를 위한 효과적인 학교보건프로그램 강화가 요구되고, 만성질환을 가진 아동 및 청소년이 부정적인 감정에 대처할 수 있도록 주기적인 상담이 필요하다. 네 번째 속성은 ‘자가간호’이다. 아동은 자가간호 수행에 대해 인식하고 있었으며, 특히 약물투여의 중요성을 인식하고 있었다. 학령기 아동 및 청소년은 스스로 만성질환에 대한 자기관리를 잘 수행할 수 있다는 자신감과 행동을 포함한 자기효능감을 지니게 되면서 스스로 만성질환 관리를 잘 할 수 있다고 여겼으며, 이러한 긍정적인 부분은 교사 및 교우에게도 영향을 미쳐 이들의 만성질환 아동에 대한 긍정적인 인식을 높였다. 이를 통해 교사 및 교우가 만성질환 아동에게 사회적 지지를 제공하게 되며, 이것은 만성질환 아동의 학업적 흥미를 촉진시키고, 학교에서의 경험을 긍정적으로 하게 하였다[ 29]. 따라서 질병에 대한 다른 사람의 부정적인 시선으로부터 만성질환 아동이 다르지 않다는 인식을 강화할 지지적 프로그램 요소가 필요하다. 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 및 청소년의 자가관리 능력 향상을 위해 자기효능감 증진 중재가 도움이 된다[ 29]. 만성질환 아동 및 청소년이 스스로 자신의 질환에 대한 자가관리의 중요성을 인식하고, 자신감을 향상시키며, 자기효능감을 증진시킬 수 있는 프로그램 개발이 필요하다. 마지막으로 다섯 번째 속성은 ‘지지적 학교환경’이다. 국내의 경우 당뇨병을 가진 아동의 약 1/3이 보건교사 도움 없이 혼자 혈당을 검사하고, 30% 이상이 보건실이 아닌 화장실에서 인슐린을 투여한다는 보고와 같이[ 28] 만성질환 학령기 아동 및 청소년의 학교 보건 관리의 문제가 제기되고 있다. 2011년에 수행된 국내 일 조사 연구에서 보건교사의 42.6%가 건강장애 아동에 대해 ‘학생파악은 하지만 직접 관리하지 않는다’라고 응답하였고, 정기적으로 관리 하는 경우는 37.6%에 불과하였으며, 43.9%가 ‘보건교사가 재량에 따라 관리한다’, 17.4%가 ‘특별한 건강관리체계가 없다’라고 응답하였다[ 30]. 그러나 이러한 취약성에도 불구하고 보건교사는 자신의 역할을 교육제공자 및 간호제공자로 인식하고 있었으며, 만성질환 학령기 아동 및 청소년의 건강관리 교육 및 중재에 대한 요구를 충족시켜야 한다고 생각하고 있었으므로 정책적으로 보건교사의 역할을 정립하고 실무지침을 제공하는 것이 필요하다[ 28]. 따라서 지지적 환경 조성을 위한 보건교사의 노력이 필요하다. 이를 위해서는 만성질환 아동을 돌볼 수 있는 제도적 장치 하에 충분한 보건교사 배치와 보건교사의 행정적 업무 부담을 줄여주는 노력이 필요할 것이다. 본 연구 결과를 토대로 다음과 같이 제언하고자 한다. 첫째, 다양한 학교상황에서 아동의 질병양상과 발달연령을 고려하여 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년을 위한 학교 건강관리 프로그램 개발이 필요하다. 둘째, 개발된 학교 건강관리 프로그램의 효과를 입증하는 연구가 필요하다.

결 론

만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년 중심의 학교 건강관리의 중요성을 인식하고 있음에도 불구하고, 이에 대한 명확한 속성이 밝혀지지 않은 상태였다. 이에 본 연구는 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년을 대상으로 한 학교 건강관리 프로그램 개발의 근거 자료를 제시하기 위해 통합적 고찰 방법을 이용하여 관련 국외 연구 18편을 체계적으로 고찰하였다. 그 결과, 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년의 학교 건강관리 인식과 관련된 속성을 도출하였고, 도출된 속성은 교우와의 관계, 안전한 학교환경, 질병 인식, 자가간호, 지지적 학교환경이었다. 본 연구의 결과를 토대로 추후 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동과 청소년을 대상으로 한 학교 건강관리 프로그램 개발이 이루어지기를 기대한다. 또한 만성질환 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년의 안전하고 지지적인 학교 환경 조성을 위한 더 많은 법적, 체계적 지원이 필요하고, 이들의 자가간호 관리 역량을 향상시킬 수 있는 중재 개발이 필요하다. 보건교사를 포함한 교사는 전체 학생을 대상으로 만성질환에 대한 이해를 돕고, 만성질환을 가진 학령기 아동 ․ 청소년과의 교우관계 개선을 위한 전략을 개발해야 할 것이다.

REFERENCES

2. Kim JH, Lee CG, Lee YA, Yang SW, Shin CH. Increasing incidence of type 1 diabetes among Korean children and adolescents: Analysis of data from a nationwide registry in Korea. Pediatric Diabetes. 2016;17(7):519-524. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12324

4. National Cancer Center. Annual report of cancer statistics in republic of Korea in 2015 [Internet]. Goyang: National Cancer Center; 2015 [cited 2020 February 15]. Available from: https://www.ncc.re.kr/cancerStatsList.ncc

7. Kim SH. A study on psychological characteristics shown in paintings by diabetic children-adolescents. Journal of The Korean Academy of Clinical Art Therapy. 2014;9(1):5-13.

9. Matlock KA, Yayah Jones NH, Corathers SD, Kichler JC. Clinical and psychosocial factors associated with suicidal ideation in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;61(4):471-477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.004

10. Gibson-Young L, Martinasek MP, Clutter M, Forrest J. Are students with asthma at increased risk for being a victim of bullying in school or cyberspace? Findings from the 2011 Florida youth risk behavior survey. The Journal of school health. 2014;84(7):429-434. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12167

13. Sohn M, Kim E, Lee JE, Kim K. Exploring positive psychology of children with type 1 diabetes focusing on subjective happiness and satisfaction with life. Child Health Nursing Research. 2015;21(2):83-90. https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2015.21.2.83

14. Lum A, Wakefield CE, Donnan B, Burns MA, Fardell JE, Marshall GM. Understanding the school experiences of children and adolescents with serious chronic illness: A systematic meta-review. Child:Care, Health and Development. 2017;43(5):645-662. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12475

15. Chao AM, Minges KE, Park C, Dumser S, Murphy KM, Grey M, et al. General life and diabetes-related stressors in early adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2016;30(2):133-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.06.005

16. Drakouli M, Petsios K, Giannakopoulou M, Patiraki E, Voutoufianaki I, Matziou V. Determinants of quality of life in children and adolescents with CHD: A systematic review. Cardiology in the Young. 2015;25(6):1027-1036. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1047951115000086

17. Woo OY Expansion of social needs and new paradigm of health education, leadership demands of school nurse teachers: From amendment of the school health law, 10 years. 2017 Korean Journal of Health Education annual autumn conference; 2017 November 18; Seoul Youth Hostel. Seoul: Korean Journal of Health Education;2017. p. 3-22.

21. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery. 2010;8(5):336-341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

23. Blaakman SW, Cohen A, Fagnano M, Halterman JS. Asthma medication adherence among urban teens: A qualitative analysis of barriers, facilitators and experiences with school-based care. The Journal of Asthma. 2014;51(5):522-529. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014.885041

24. Schwartz FL, Denham S, Heh V, Wapner A, Shubrook J. Experiences of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes in school: Survey of children, parents, and schools. Diabetes Spectrum. 2010;23(1):47-55. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.23.1.47

26. Hamilton H, Knudsen G, Vaina CL, Smith M, Paul SP. Children and young people with diabetes: Recognition and management. British Journal of Nursing. 2017;26(6):340-347. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.6.340

27. Alvar CM, Coddington JA, Foli KJ, Ahmed AH. Depression in the school-aged child with type 1 diabetes: Implications for pediatric primary care providers. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2018;32(1):43-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.07.002

29. Mickley KL, Burkhart PV, Sigler AN. Promoting normal development and self-efficacy in school-age children managing chronic conditions. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2013;48(2):319-328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2013.01.009

30. Oh J. Perception of health impairment and hospital school and status of management to children with health impairment on elementary school health teachers. InJe Journal. 2011;26(1):369-383.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the search process.

Table 1.

|

Key word |

Subject

|

Context

|

|

Child* |

Experience* |

School |

Chronic disease |

|

Synonyms |

|

child* or young person* or teen* or adolescent* or pediatric* or paediatric* or pupil* or kid* or student* |

experience* or perspective* or perception* or attitude* or feeling* or belief* or reality or phenom* or view* or understand* or barrier* or facilitate* or challenge* or determine* or considerate* or need* |

school* or school-based or school nurse* or nurse teacher* or school health nursing* or peer* |

chronic condition* or chronic disease* or chronic ill* or long-term condition* or asthma* or diabetes or diabetic or epilepsy* or seizure or cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis or congenital heart or congenital cardiac or inflammatory bowel or Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis or chronic kidney disease or muscular dystrophy or spina bifida or chronic pain or cancer or malignant or leukemia or allergy or allergies or allergic or atopic dermatitis or atopy or arthritis or eczema or haematology* or hematology* or hemophilia* or haemophilia* or celiac or sickle |

|

Inclusion criteria |

• |

Articles written and published in English |

|

• |

Peer-reviewed published articles |

|

• |

Articles analyzing the school health care experiences of school-aged children and adolescents with chronic disease |

|

• |

In-press articles |

|

Exclusion criteria |

• |

Articles that did not include children/school-aged participants |

|

• |

Articles that did not analyze participants with chronic disease |

|

• |

Articles that did not deal with health care experiences at school |

|

• |

Articles involving hospitalized children, technically dependent children, or children with physical disabilities |

|

• |

Master's theses and doctoral dissertations, letters to the editor, conference presentation papers |

|

• |

Descriptive research, review research, and intervention research |

Table 2.

Key Findings of Selected Articles (N=18)

|

Author |

Research design |

Disease |

Goal |

Instruments |

Country |

Sample |

Age (year) |

Key findings |

Themes and subthemes |

|

Yang et al., (2018) [1] |

Qualitative: thematic analysis |

Type I DM |

To describe perceptions of adolescents with T1DM regarding the responses of their peers to their diabetes self-management in school settings |

NA |

Taiwan |

10 |

12~17 |

Peers sought knowledge about diabetes in school |

1. Peer-related issues |

|

Peers had curiosity, enthusiasm, and fearfulness regarding diabetes management in school |

|

1.1. Positive perception |

|

Peers isolated adolescents with diabetes and bullied them in school |

|

1.2. Negative perception |

|

Naman et al., (2018) [2] |

Mixed-methods: grounded theory and survey |

Asthma |

To explore students' experiences with asthma care and perceptions of facilitators and barriers to care at school |

Self-made: an informal questionnaire about asthma care practices, perceptions toward school asthma management |

USA |

15 |

8~11 |

Concerns about asthma management (37.5%) |

1. Peer-related issues |

|

Negative impact of chronic disease on peer relationships (50%) |

|

1.1. Positive perception |

|

Unhelpful school nurses |

|

1.2. Negative perception |

|

Support of school staff and peers, self-confidence, and self-efficacy, perception for normal as facilitators in asthma management |

2. Safe school environment |

|

Unsupportive school staff and peers and ineffective use of inhalers as barriers for asthma management |

|

2.3. Roles of the school nurse |

|

3. Self-perception of existing disease |

|

3.3. Challenges of an existing disease |

|

4. Self-management |

|

4.3. Conducting self-management |

|

5. Supportive school environment |

|

5.1. Support by teachers, peers, and health care providers |

|

Haridasa et al., (2018) [3] |

Qualitative: grounded theory |

Sickle cell disease |

To identify the perceptions of children with sickle cell disease in the school environment |

NA |

USA |

14 |

Mean 8.18 |

Difficulties in communication with peers and teachers |

1. Peer-related issues |

|

Limited school activities due to their physical condition |

|

1.1. Positive perception |

|

Administrative support for existing disease management |

|

1.2. Negative perception |

|

Making up missed learning opportunities |

2. Safe school environment |

|

Conducting self-management |

|

2.6. Administrative support |

|

Need to improve peers' awareness of the disease |

3. Self-perception of existing disease |

|

3.3. Challenges of an existing disease |

|

4. Self-management |

|

4.3. Conducting self-management |

|

5. Supportive school environment |

|

5.4. Learning opportunities |

|

Sparapani et al., (2017) [4] |

Qualitative: content analysis |

Type I DM |

To analyze the experiences of children with T1DM in self-managing the disease at school |

NA |

Brazil |

19 |

7~12 |

Ineffective information-sharing for children's health among school teachers |

1. Peer related issues |

|

Lack of knowledge of diabetes among teachers and peers |

|

1.2. Negative perception |

|

Feeling support from school staff, peers, and medical staff |

2. Safe school environment |

|

2.4. Training for school teachers |

|

2.5. Sharing of information and role delineation among school staff |

|

5. Supportive school environment |

|

5.1. Support by teachers, peers, and health care providers |

|

Ottosson et al., (2017) [5] |

Quantitative: survey |

Type I DM |

To investigate whether children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes would report a higher quality of support in diabetes self-care |

Self-made: an informal questionnaire about attitudes to diabetes care in school |

Sweden |

n=317 (2008), n=570 (2015) |

6~12 |

Lack of confidence in managing |

2. Safe school environment |

|

hypoglycemia among school staff (41%) |

|

2.1. Safe and convenient environment for medication and testing |

|

Discomfort in taking medication (12%) |

|

2.4. Training for school teachers |

|

Discrimination on the basis of a medical condition (14%) |

3. Self-perception of existing disease |

|

Experiences of hypoglycemia at least once a week (84%) |

|

3.1. Experiences of symptoms and complications |

|

5. Supportive school environment |

|

5.1. Discrimination on the basis of a medical condition |

|

Walker & Reznik, (2014) [6] |

Qualitative |

Asthma |

To explore children's perceptions of the impact of in-school asthma management on physical activity |

NA |

USA |

23 |

8~10 |

Experiences of asthma symptoms |

2. Safe school environment |

|

Methods to control asthma and to prevent asthma during in-school physical activity |

|

2.1. Safe and convenient environment for medication and testing |

|

Limited accessibility to asthma medication |

3. Self-perception of existing disease |

|

Others' negative attitudes about use of the medication |

|

3.1. Experiences of symptoms and complications |

|

3.3. Challenges of an existing disease |

|

4. Self-management |

|

4.3. Conducting self-management |

|

Sarnblad et al., (2014) [7] |

Quantitative: survey |

Type I DM |

To investigate attitudes to diabetes care in school reported by children with type I diabetes, their parents, and their diabetes teams |

Self-made: an informal questionnaire about attitudes to diabetes care in school |

Sweden |

317 |

7~15 |

Fear of hypoglycemia during class (18%) |

2. Safe school environment |

|

Association between experiences of hypoglycemia and glycosylated hemoglobin |

|

2.5. Sharing of information and role delineation among school staff |

|

Unsatisfactory multidisciplinary management in school (18%) |

3. Self-perception of existing disease |

|

3.1. Experiences of symptoms and complications |

|

Blaakman et al., (2014) [8] |

Qualitative: content analysis |

Asthma |

To understand urban teens' experiences with asthma management, preventive medication adherence, and participation in a school-based intervention |

NA |

USA |

28 |

12~15 |

Awareness of the importance of medication adherence |

4. Self-management |

|

Having trouble remembering to take medications |

|

4.1. Perceived significance of self-management |

|

Barriers to medication adherence: other priorities such as social issues than taking medication |

|

4.2. Challenges and facilitators for self-management |

|

Facilitators of medication adherence: good relationships with school nurses |

|

Existing facilitators and barriers to medication adherence in school |

|

Wang, Brown, & Honer, (2013) [9] |

Qualitative: hermeneutical phenomenological approach |

Type I DM |

To investigate school-based lived experiences |

NA |

Taiwan |

14 |

12~17 |

The point of distinction from peers |

1. Peer-related issues |

|

Disguising their disease due to misunderstanding of the disease and immature response of peers |

|

1.3. Coping with peer-related issues |

|

Temptation of high-calorie foods |

2. Safe school environment |

|

Ineffective school health nursing care |

|

2.3. Roles of the school nurse |

|

Awareness of the importance of self-management |

3. Self-perception of existing disease |

|

3.3. Challenges of an existing disease |

|

4. Self-management |

|

4.1. Perceived significance of self-management |

|

4.2. Challenges and facilitators for self-management |

|

Tang, Chen, & Wang, (2013) [10] |

Quantitative: survey |

Type I DM |

To investigate whether school support influences self-care behaviors and life satisfaction |

Diabetes self-care behavior scale |

Taiwan |

139 |

10~18 |

School support for effective self-management and life satisfaction |

5. Supportive school environment |

|

Perceived school support scale |

|

5.1. Support by teachers, peers, and health care providers |

|

Life satisfaction scale |

|

Engelke et al., (2011) [11] |

Quantitative: survey |

Type I DM |

To describe the impact of school nurse interventions on quality of life |

PedsQL 3.0 Type I diabetes module |

USA |

25 |

5~17 |

Positive impact of care coordination by school nurses on increased quality of life of students (13〜 17 years old) |

2. Safe school environment |

|

2.3. Roles of the school nurse |

|

Krenitsky-Korn, (2011) [12] |

Quantitative: survey |

Asthma |

To investigate the correlation between the attitudes of high school students with and without asthma toward school health services |

Self-made: an informal questionnaire about attitudes to and comfort with school nurse service、 school health services |

USA |

28 |

High school students |

Higher satisfaction with support of school health care in adolescents with chronic diseases |

2. Safe school environment |

|

Well-being through communication with school nurses and well-supported care by school nurses (56%) |

|

2.3. Roles of the school nurse |

|

5. Supportive school environment |

|

5.1. Support by teachers, peers, and health care providers |

|

Wang, Brown, & Honer, (2010) [13] |

Qualitative: hermeneutical phenomen- ological approach |

Type I DM |

To explore children's perceptions to manage their diabetes while at school |

NA |

Taiwan |

2 |

12,16 |

Adolescents with diabetes learn diabetes management skills |

1. Peer-related issues |

|

Seeking ways to feel comfortable in relationships with peers in school |

|

1.1. Positive perception |

|

Trying to learn to not be different from peers |

3. Self-perception of existing disease |

|

3.3. Challenges of an existing disease |

|

4. Self-management |

|

4.3. Conducting self-management |

|

Schwartz et al., (2010) [14] |

Quantitative: survey |

Type I DM |

To identify the diabetes-related experiences of the children and adolescents, their parents, and their school personnel |

Self-made: an informal questionnaire about diabetes-related experiences in school |

USA |

80 |

Kindergarten to 12th grade |

Treated differently from other students (45%) |

1. Peer related issues |

|

Unsupportive school environment (blame 37.5%, prevented from managing diabetes 29.1%) |

|

1.2. Negative perception |

|

Embarrassed in front of other students (11.4%) |

4. Self-management |

|

Challenges in managing self-management (23~28%) |

|

4.2. Challenges and facilitators for self-management |

|

5. Supportive school environment |

|

5.1. Support by teachers, peers, and health care providers |

|

5.2. Discrimination on the basis of a medical condition |

|

Amillategui et al., (2009) [15] |

Quantitative: survey |

Type I DM |

To identify the special needs of children with type 1 diabetes at primary school |

Self-made: an informal questionnaire about general situation in management, worries about type 1 diabetes, possible actions to improve integration |

Spain |

152 |

6~13 |

Unassisted blood testing (53%) |

1. Peer related issues |

|

Worries about not being able to administer insulin by oneself (60%) |

|

1.2. Negative perception |

|

Insufficient preparation of glucagon in an emergency situation |

2. Safe school environment |

|

Worries about not being able to recognize hypoglycemia (75%) |

|

2.2. Emergency response procedure |

|

Recognition of physical education teacher a hypoglycemic episode (42%) |

|

2.4. Training for school teachers |

|

Immature response among peers (18%) |

|

2.6. Administrative support |

|

Usefulness of written information (88%) |

3. Self-perception of existing disease |

|

Perception of difference with peers (38%) |

|

3.1. Experiences of symptoms and complications |

|

3.3. Challenges of an existing disease |

|

5. Supportive school environment |

|

5.1. Support by teachers, peers, and health care providers |

|

Lehmkuhl & Nabors, (2008) [16] |

Quantitative: survey |

Type I DM |

To assess children's perceptions of their satisfaction with support from school nurses, teachers, and friends. |

Children's satisfaction with support from nurses, teachers, and classroom friends (revised How is School Scale) |

USA |

23 |

8~14 |

Higher satisfaction regarding care by school nurses compared with those of teachers and peers |

2. Safe school environment |

|

Need for participation in after school activities |

|

2.3. Roles of school nurse |

|

Negative impact of sadness and perception that it was less fair to have diabetes on glycosylated hemoglobin levels |

3. Self-perception of existing disease |

|

Positive impact of a supportive school environment on glycosylated hemoglobin levels |

|

3.2. Negative emotion |

|

5. Supportive school environment |

|

5.1. Support by teachers, peers, and health care providers |

|

5.4. Learning opportunities |

|

Engelke et al., (2008) [17] |

Quantitative: survey |

Asthma, diabetes, severe allergies, seizures, or sickle-cell anemia |

To track the academic, health, and quality of life outcomes following the case management, by school nurses |

PedsQL3.0SF22 asthma module |

USA |

114 |

5~19 |

Improvements in quality of life and gained skills and knowledge to manage their illness more effectively through case management by school nurses |

2. Safe school environment |

|

2.3. Roles of the school nurse |

|

Smith et al., (2008) [18] |

Qualitative: an iterative approach |

Endocrine, rheumatology respimtory, and gastro-enterology |

To examine the experiences and concerns of young people with chronic conditions in managing medication at school |

NA |

UK |

27 |

6~19 |

Carrying their medication, keeping their medication at school |

1. Peer related issues |

|

Privacy in administering medication |

|

1.1. Positive perception |

|

Experiences of the side effects of medication |

|

1.2. Negative perception |

|

Peers' understanding and help about taking medication, peers noticing hypoglycemia |

2. Safe school environment |

|

Discomfort with recognition of their disease by other persons, skipping taking medication |

|

2.4. Training for school teachers |

|

Medication training for school staffs |

|

2.5. Sharing of information and role delineation among school staffs |

|

Understanding of taking medication for students with chronic disease among school staff |

3. Self-perception of existing disease |

|

Sensitive responses to the needs of the children |

|

3.1. Experiences of symptoms and complications |

|

4. Self-management |

|

4.1. Perceived significance of self-management |

|

5. Supportive school environment |

|

5.1. Supportive school environment |

|

5.3. Privacy |

Table 3.

The Themes of Perceptions Regarding School Health Care among Students with Chronic Disease

|

Themes |

Subthemes |

|

1. Peer-related issues |

1.1. Positive perception |

|

1.2. Negative perception |

|

1.3. Coping with peer-related issues |

|

2. Safe school environment |

2.1. Safe and convenient environment for medication and testing |

|

2.2. Emergency response procedure |

|

2.3. Roles of the school nurse |

|

2.4. Training for school professionals |

|

2.5. Sharing of information and role delineation among school staff |

|

2.6. Administrative support |

|

3. Self-perception of an existing disease |

3.1. Experiences of symptoms and complications |

|

3.2. Negative emotion |

|

3.3. Challenges of an existing disease |

|

4. Self-management |

4.1. Perceived significance of self-management |

|

4.2. Challenges and facilitators for self-management |

|

4.3. Conducting self-management |

|

5. Supportive school environment |

5.1. Support by teachers, peers, and health care providers |

|

5.2. Discrimination on the basis of a medical condition |

|

5.3. Privacy |

|

5.4. Learning opportunities |

|

|