Lee: Structural Equation Model for Psychosocial Adjustment in North Korean Adolescent Refugees

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to identify variables influencing the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees in order to establish a structural equation model and design an intervention strategy to improve psychosocial adjustment.

Methods

The subjects included 290 North Korean adolescent refugees aged 16~24 years who were enrolled in alternative schools or regional adaptation centers. They were surveyed using a structured questionnaire.

Results

The goodness of fit measures of the model were as follows: x2=131.20 (p<.001), GFI=.93, CFI=.91, TLI=.86, RMSEA=.08, and SRMR=.07. The results estimated from the structural equation model indicated a good fit of data to the hypothesized model, which proposed that stress and emotional intelligence are associated with psychosocial adjustment. The major variables influencing psychosocial adjustment were stress, emotional intelligence, which was a significant direct effect, whereas attitude of parenting showed an indirect effect on psychosocial adjustment through emotional intelligence. These variables account for 50.0% of psychosocial adjustment.

Conclusion

It is necessary to develop a program and intervention plan that can enhance emotional intelligence and thereby relieve the stress of North Korean adolescent refugees. The program should also include parenting education so that parents have positive attitude of parenting.

Key words: North Korea; Refugees; Adolescent; Adjustment

INTRODUCTION

The total number of North Korean refugees who enter South Korea is steadily increasing, which means the proportion of North Korean adolescent refugees is also increasing. The number of North Korean adolescent refugees was 2,538 in April 2017 [ 1]. Adolescence is the time when children develop their self-identity and prepare for adulthood, while experiencing significant physical and mental changes [ 2]. North Korean adolescent refugees are expected to have difficulties in normal growth and development as they settle into South Korean society due to various traumatic experiences they have gone through in the process of entering South Korea since escaping from North Korea. These experiences include threats to their personal safety, separation from family members, and the fear of repatriation to North Korea. Due to trauma in the process of defecting from North Korea, longing and guilt for their family, fear of South Korean life, and adjustment problems, North Korean adolescent refugees experience varying degrees of physical abnormal symptoms or serious psychological pains such as depression or a sense of inferiority [ 3]. According to a study by Sam et al. [ 4] psychological adjustment is the concept of stress coping and is affected by personal characteristics, changes in life, coping strategies, and social support. In contrast, socio-cultural adjustment is described as a paradigm of social skills and cultural learning. For this reason, both psychological and socioenvironmental factors should be considered in order to help North Korean adolescent refugees grow into productive members of South Korean society. However, despite experiencing similar types of stress under a similar environment, the amount of stress individuals perceive can vary because stress may incur from the interplay between individuals and their internal, external, and environmental systems. North Korean adolescent refugees may face different problems according to their personal background, motive for defecting from North Korea, length and experience of stay in a third country, and the presence or absence of family. Their emotional anxiety and stress caused by rapid psychological changes are expected to be added due to differences in educational system between North Korea and South Korea and unstable family structures. As such, there is a desperate need for intervention strategies that promote psychological adjustment-strategies that help them relieve and overcome the stress they experienced through countless risks in the process of defecting from North Korea and the stress caused by settling into a new cultural environment in South Korea. Adolescents’ social maladjustment, including social deviance, has mostly been caused by parents’ wrong guidance or improper relationship with parents, such as child abuse, indifference, or verbal violence [ 5]. The negative attitude that parents show when they raise their children has a negative effect on adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment, which is highly likely to lead to various juvenile problems: running away from home, dropping out of school, or school violence [ 5]. When parents use corporal punishment, reject or show an indifferent attitude, are not satisfied with their children, or display authoritarian or an inconsistent attitude of parenting, children were found to show problematic attitudes such as expressions of anger, not being obedient, or having a low ability to control emotion [ 6]. The attitudes of parenting of North Korean parent refugees that was formed due to various social and cultural experiences during their stay in China or a third country is also likely to be transferred to children, or at least shared with them. As the socioeconomic stress they have experienced is also expected to negatively affect the attitude of parenting [ 7], there is a need to identify the association between the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees and their parents’ attitude of parenting. Adolescence is commonly characterized by mental and physical instability due to developmental characteristics and emotionally maladaptive behavior in school and social life, as it is a period when stress is maximized due to rapid changes in their surrounding environment and internal changes [ 2]. Emotional intelligence is the ability to motivate oneself, control impulses, adjust mood, and show empathy towards others experiencing frustrating situations [ 8]. One can be well adapted to social life if they perceive the emotions of themselves and other people, and then control their emotions well. The ability to perceive emotions is the ability to exactly infer others’ emotions and feelings. Children who lack this ability often suffer from difficulties in situation of special requests or intentions [ 9]. Children having a high empathic ability have good personal relationships, and the higher their ability to understand others’ emotions, the more positive and optimistic perspective they have toward a given environment [ 10]. In other words, children having high emotional intelligence may be well adapted in their surrounding environment and can adjust their emotional state to be positive and pleasant. If they cannot adjust theirs and others’ emotions effectively, they may show selfish, aggressive, and anti-social behaviors [ 2]. Furthermore, in the context of their home environment, emotional intelligence is influenced by the attitude of their parents. Therefore, the lack of a positive attitude in parenting from mothers can negatively affect the ability of elementary school students and adolescents to recognize, understand, and adjust their own emotions and others [ 11]. Hence, there is a need to investigate the effect of attitude of parenting on emotional intelligence and what relationship the attitude of parents has on adolescents’ their psychosocial adjustment since personal factors and family factors surrounding North Korean adolescent refugees are not one single thing but combine to influence to each other. In previous studies, research that analyzes a structural equation model for factors that influence psychosocial adjustment remains insufficient, aside from research into the post-traumatic stress of North Korean adolescent refugees [ 3, 12], stress and social support [ 13], cultural adaptation [ 14], policy support [ 15, 16], and psychosocial adjustment through regression analyses [ 17, 18]. It is important to understand the family break-up and conflicts with family that North Korean adolescent refugees experience in the process of entering South Korea, in addition to the academic burden and difficulties in social and cultural adjustment they experience after entering South Korea in order to find ways to help them adapt to South Korean society. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the structural relationship between post-traumatic stress, cultural adaptation stress, attitude of parenting, emotional intelligence, and the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees based on the theory of stress and coping by Lazarus and Folkman [ 19], and through these findings provide a baseline for preparing an intervention strategy to assist in their psychosocial adjustment.

1. Objectives

The purpose of this study is to construct a hypothesis model based on previous studies to explain and predict the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees to ultimately find a cause and effect path among the diverse variables. Grasping a cause-and-effect relationship among factors that influences the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees, and to them rank these factors in priority order is expected to enable the development of an integrated approach to nursing to hasten the adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees by developing psychosocial adjustment protocols.

2. Research Hypothesis

• Stress incurred by North Korean adolescent refugees will affect their emotional intelligence. • Attitude of parenting perceived by North Korean adolescent refugees will affect their emotional intelligence. • Stress of North Korean adolescent refugees will affect their psychosocial adjustment. • Attitude of parenting perceived by North Korean adolescent refugees will affect their psychosocial adjustment. • Emotional intelligence of North Korean adolescent refugees will affect their psychosocial adjustment.

METHODS

1. Research Design

This study was designed to construct and verify a structural model that explains the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees and determine a cause- and-effect relationship between variables that influence their psychosocial adjustment, using the concept of emotional intelligence from Salovey and Mayer [ 11] as mediating variable based on the theory of stress and coping from Lazarus and Folkman [ 19].

2. Subjects

The subjects in this study are North Korean adolescent refugees aged between 16 and 24, who registered in alternative schools in the Seoul and Gyeonggi metropolitan areas, Daejeon and Chungcheong area, Yeomyung School, Hangyeore High School, or a regional adjustment center, who voluntarily consented to participate in this research, under the concurrent agreement of their parents or legal agent. In general, in structural equation model, measuring variables 5~10 times is the minimum recommended level and an ideal sample size is 200 people; 200~400 samples are desired for structural model analyses [ 20]. In structural model analyses, the most common estimation method is the Maximum Likelihood Estimate (MLE), in which 10~400 samples are considered appropriate [ 20]. This study selected 324 samples, of which 34 samples were dropped, with 290 samples finally used for analysis. Therefore, the sample size in this study meets the minimum recommendation that 200 samples are needed to verify the model as single standard value to satisfy the threshold.

3. Research Instrument

1) Attitude of parenting

In terms of attitude of parenting, negative attitudes such as neglect, abuse, and inconsistency were used based on the parenting test developed by Kim [ 21]. Measurement tools were used after its use was approved by the developer prior to data collection. Responses for each item were developed to obtain scores ranging from 1 point for “strongly disagree” to 5 points for “strongly agree” based on five-point Likert scale, with higher points indicating a higher level of the corresponding behavior. Cronbach’s ⍺ at the time of development was .84, .86 for neglect, .87, .89 for abuse, and .75, .80 for inconsistency [ 21], for parents. Cronbach’s ⍺ in this study was .86 for neglect, .90 for abuse, and .81 for inconsistency.

2) Stress

Stress in this study was divided into post-traumatic stress, characterizing the special characteristics of escaping North Korea, and cultural adaptation stress, which North Korean adolescent refugees experience while settling into South Korean society. Measurement tools were used after their use was approved by the developer, prior to data collection.

(1) Post-traumatic stress

For post-traumatic stress, the scale validated for North Korean adolescent refugees in a study of Kim et al. [ 22] was used. This scale is composed of 17 items, measuring primary symptoms of post-traumatic stress such as re-experience, avoidance or emotional numbness, and hyperarousal of traumatic events, and 6 items measuring complex-Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (complex-PTSD). Each item obtains scores ranging from 0 points for “never” to 3 points for “almost every day”, with higher points indicating a higher post-traumatic stress level. Cronbach’s ⍺ was .94 in the study by Kim et al. [ 22], and was .92 in this study.

(2) Cultural adaptation stress

For cultural adaptation stress, the scale validated for North Korean adolescent refugees in a study by Kim et al. [ 22] was used. This scale is composed of 16 items regarding 5 subfactors: sense of difference, culture shock, discrimination, marginalization, and homesickness. Based on a five-point scale, each item obtains scores ranging from 0 points for “strongly disagree” to 4 points for “strongly agree”, with higher points indicating a higher cultural adaptation stress level. Cronbach’s ⍺ was .85 in the study by Kim et al. [ 22], and was .95 in this study.

3) Emotional intelligence

As a scale for emotional intelligence for adolescents developed by Moon [ 23], a total of 40 items regarding five subfactors were measured: emotional awareness and expression, empathy, emotional facilitation of thinking, using emotional knowledge, and emotional adjustment. Based on five-point Likert scale each item obtains scores ranging from 1 point for “strongly disagree” to 5 points for “strongly agree”, with higher points indicating a higher emotional intelligence. Cronbach’s ⍺ was .65 at the time of development and .79 in this study.

4) Psychosocial adjustment

To measure the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees, withdrawal, depression/anxiety, delinquency, and aggression from the Korean version of the Korean Youth Self Report (K-YSR) [ 24] were used. Psychological adjustment is composed of 7 items regarding withdrawal and 16 items regarding depression/anxiety. Each item obtains scores ranging from 1 point for “strongly disagree” to 3 points for “strongly agree”, with higher points indicating higher withdrawal and depression/anxiety. Social adjustment is composed of 11 items evaluating delinquency and 19 items evaluating aggression. Each item obtains scores ranging from 1 point for “strongly disagree” to 3 points for “strongly agree”, with higher points indicating higher delinquency and aggression. Cronbach’s ⍺ was .63~.85 in K-YSR [ 24], with Cronbach’s ⍺ subfactors in this study being .76 for withdrawal, .86 for depression/anxiety, .71 for delinquency, and .87 for aggression.

4. Data Collection Process and Ethical Consideration

This study was conducted after being approved by an Institutional Review Board (Approval No.: 16-05-02-1221). The purpose of the study and data collection method were explained to the related department and director of the institution before data collection and subject recruiting was allowed. The subjects of this study were North Korean adolescent refugees who voluntarily consented to participate in this research, upon approval of their parents or legal agent. Data was collected from January 5, 2017 to January 4, 2018. The survey was conducted during breaks and activity times outside of regular class hours, with the help of school teachers or regional working-level staff, after a trained researcher explained the purpose and aim of research. For the areas that were difficult to be understood during explanations, a North Korean refugee volunteer provided extra explanations. The subjects were informed that they could withdraw from the survey anytime if they did not want to reply, that there would be no subsequent disadvantage or discrimination, and that all data provided would be anonymous. The time required to reply to the questionnaire was about 15~20 minutes, and all questionnaires were collected immediately after response were provided and stored in a designated place that was managed by researchers in order to prevent the leakage of personal information and survey contents. To maintain the security of the computer that stored the collected data, a password was used and only researchers were permitted to access the device. A small gift (stationery products) was offered to all subjects who completed the survey.

5. Data Analysis

The collected data was analyzed using the SPSS 21.0 statistics program and AMOS Ver. 22.0 software. General characteristics and descriptive statistics of major variables were presented based on frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. The correlation between all variables was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients.

The normality of each sample in the structural model analysis was confirmed based on its mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis using SPSS 21.0. The measurement model was verified via a confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 22.0, and a structural equation model analysis was performed to explore structural relationships. The estimation of parameters for the structural equation model was performed using MLE, and the goodness-of-fit of the model was analyzed using x2, in addition to the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), the Comparative Normed of Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). The significance of the estimation coefficient based on the path of the hypothetical model was analyzed based on the Critical Ratio (CR) and p-value (p<.050). A bootstrap method was used to verify if the mediation effect, an indirect effect, was significant.

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics of Subjects

The subjects of this study consisted of 24.8% male students and 75.2% female students. The mean age was 20.03±3.05 years, with 20 years old or younger being 52.8% and 21 years old and older being 47.2%. Regarding school status, the largest portion were alternative school students at 39.9% of the subjects; elementary school students, middle school students, high school students, university students, and people who are preparing for qualification examinations or job applicants were 5.2%, 6.9%, 11.5%, 7.7%, and 28.8%, respectively. Meanwhile, subjects who replied that they lived alone, that they live with one parent or both parents, that they live with siblings or relatives, and who replied that they live with friends or guardians were 41.7%, 39.0%, 11.4%, and 7.9%, respectively. The satisfaction level of subjects’ relationships with friends was 3.16±2.14 points out of 10, and academic stress and anxiety toward the future of subjects were 6.25±2.88 points and 6.18±2.87 points out of 10, respectively.

2. Descriptive Statistics of Research Variables

Descriptive statistics of the research variables used in the measurement model of this study are as follows ( Table 1). Neglect, a subfactor of negative attitude of parenting perceived by subjects, was 2.14±0.89 out of 5 points, with inconsistency and abuse being 2.46±0.79 and 2.16±0.94, respectively. Post-traumatic stress or stress perceived by subjects was 1.84±0.59 out of 4 points, whereas cultural adaptation stress was 2.38±0.72 out of 5 points. Empathy, facilitation thinking, and using emotional knowledge, subfactors of emotional intelligence, were 3.44±0.50, 3.57±0.47, and 3.64±0.54 out of 5 points, respectively. Shrinking, delinquency, and aggression, subfactors of psychosocial adjustment, were 1.17±0.42, 1.35±0.28, and 1.44±0.30 out of 3 points, respectively. As the absolute value of skewness and kurtosis of variables used in this study is distributed in the range of ±3, the data was found not to deviate from the hypothesis of normal distribution.

3. Correlation of Major Research Variables

In the analysis of correlation among the variables used in this study, shrinking, a subfactor of the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees, showed a significant positive correlation with neglect of parent (r=.28, p<.001), inconsistent attitude of parenting (r=.26, p<.001), abuse (r=.21, p<.001), post-traumatic stress (r=.50, p<.001), and cultural adaptation stress (r=.46, p<.001).

The delinquency of North Korean adolescent refugees displayed a significant positive correlation with neglect of parents (r=.36, p<.001), inconsistent attitude of parenting (r=.25, p<.001), abuse (r=.39, p<.001), post-traumatic stress (r=.40, p<.001), and cultural adaptation stress (r=.39, p<.001), while there was a significant negative correlation with empathy (r=-.12, p=.036) and facilitation thinking (r=-.16, p=.005), subfactors of emotional intelligence. Aggression of North Korean adolescent refugees had a significant positive correlation with neglect of parents (r=.32, p<.001), inconsistent attitude of parenting (r=.22, p<.001), abuse (r=.40, p<.001), post-traumatic stress (r=.45, p<.001), and cultural adaptation stress (r=.36, p<.001), while there was a negative correlation with facilitation thinking (r=-.24, p<.001), a subfactor of emotional intelligence ( Table 2).

4. Testing of Psychosocial Adjustment Structural Model of North Korean Adolescent Refugees

This study tested a hypothetical model that set stress, negative attitude of parenting, and emotional intelligence as observed variables using a structured tool in order to investigate factors that influence the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees. A confirmatory factor analysis for the measurement model was conducted first to verify model estimation possibility and fitness and the research model was then tested.

1) Confirmatory factor analysis

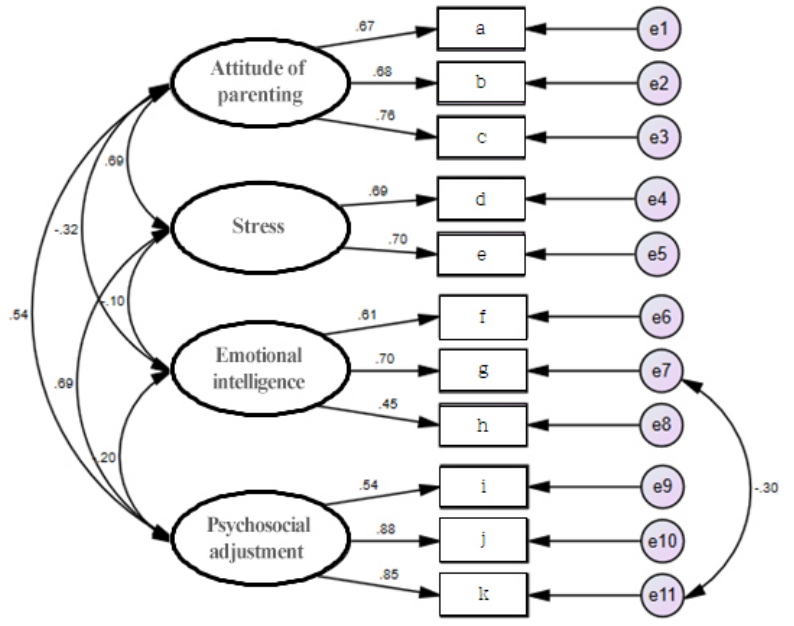

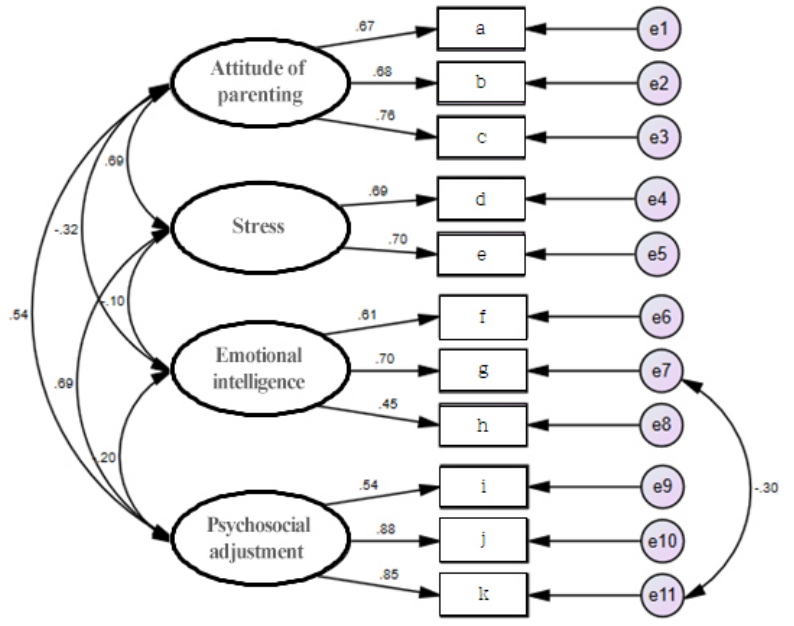

In the confirmatory factor analysis, stress, negative attitude of parenting, and emotional intelligence were confirmed to be a relatively good measurement model for explaining the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees. At this time, factors having a low loading were eliminated from the emotional intelligence and psychosocial adjustment. It is possible that the link between the error terms is an interrelated variable of endogenous latent variables ( Figure 1).

(1) Convergent validity

The validity was evaluated through Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Construct Reliability (CR) which present the coincidence between latent variables and measurement variables, in which the CR values of each construct concept were all 0.70 or more, which was significant. The AVE value of each construct concept value was .50 or more, confirming that this model has convergent validity ( Table 1).

(2) Discriminant validity

The discriminant validity expresses the difference between different latent variables and the correlation coefficient between latent variables of the measurement model. For this study, the validity was in the range of -.01~.76. Since the absolute values of correlation coefficients were all less than .85, it was confirmed that this model has discriminant validity.

2) Goodness-of-fit test of measurement model

The goodness-of-fit of measurement model tested in this study is as follows. The goodness-of-fit index of this study was found to be x2=131.20 ( p<.001), GFI=.93, CFI=.91, TLI=.86, RMSEA=.08, and SRMR=.07. Although the hypothetical model was found not to be fit with x2=131.20 ( p<.001), as x2 was sensitive to the number of samples, the value of N x2 [ 18], which was less sensitive to the number of samples, was calculated to be 3.43, which confirmed appropriate fitness (value between 2 and 5). Next, the TLI value did not meet the standard value. However, since GFI, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR values showed good results, the measurement model for hypothetical model of psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees set in this study was deemed to be valid.

3) Analysis of final model

The goodness-of-fit of the final model suggested in this study is as follows. The goodness-of-fit index of the research model in this study was found to be x2=131.20 ( p<.001), GFI=.93, CFI=.91, TLI=.88, RMSEA=.08, and SRMR=.07. Though an incremental fit index TLI showed slightly low figures, as CFI, GFI, RMSEA, and SRMR were found to fit, the overall model was deemed to have no problem in performing the analysis. Three paths out of the five suggested in the hypothetical model of this study were found to be significant; the three supported paths and final model are shown in Figure 2. Direct effect, indirect effect, and total effect of the factors related to North Korean adolescent refugees are shown in Table 3. “Stress of North Korean adolescent refugees will have effect emotional intelligence.”, Hypothesis 1, was rejected because the direct effect was not statistically significant (β=.24, CR=1.48, p=.253). The direct effect of “Negative attitude of parenting perceived by North Korean adolescent refugees will effect emotional intelligence.”, Hypothesis 2, was statistically significant (β=-.48, CR=-2.85, p=.009). The direct effect of “Stress of North Korean adolescent refugees will effect psychosocial adjustment.”, Hypothesis 3, was statistically significant (β=.64, CR=4.10, p=.009). “Negative attitude of parenting perceived by North Korean adolescent refugees will effect psychosocial adjustment.”, Hypothesis 4, was rejected because the direct effect was not statistically significant (β=.06, CR=0.44, p=.681). The direct effect of “Emotional intelligence of North Korean adolescent refugees will effect psychosocial adjustment.”, Hypothesis 5, was statistically significant (β=-.12, CR=-1.41, p=.033). The psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees was explained by 50.0% in total as being based on stress, negative attitude of parenting, and emotional intelligence. In other words, when the stress was high and emotional intelligence was low, the negative parenting attitudes are mediated by relying on the emotional intelligence of the adolescent, a technique that resulted in increased shrinking, delinquency, and aggression, which are all subfactors of psychosocial adjustment.

DISCUSSION

To have a good quality life in South Korea, it is important to adapt to new changes in various areas. This study was conducted in order to construct and verify a structural model based on the theory of stress and coping by Lazarus and Folkman [ 19] using the concept of emotional intelligence from Salovey and Mayer [ 11] as a mediating variable that explains the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees, to subsequently establish nursing intervention strategies to increase psychosocial adjustments. In the results of this study, the primary variables that affected the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees were stress, negative attitude of parenting, and emotional intelligence, and in case of negative attitude of parenting, only indirect effects were significant. From these results, discussions based on the major results are as follows.

The variables that affected the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees through direct paths were stress consisting of post-traumatic stress and cultural adaptation stress. Adolescents experience various physical, psychological, and social traumas in the process of escaping North Korea and entering South Korea. Not only that, they experience various mental traumas such as fear of detection or arrest, physical injuries, and being split from or losing family. Such traumatic experiences of North Korean adolescent refugees have been reported to have similar rates as that of adults [ 12]. Such traumatic experiences affect their adaptation into South Korean society. In fact, North Korean adolescent refugees experience many psychological symptoms, including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or depression, and commonly express psychological pain through delinquency, deviant behavior, aggressive, and hostile behaviors [ 25]. As such, there is a need for a comprehensive support system that considers environmental factors for North Korean adolescent refugees, such as trauma experienced in North Korean life and in the process of escaping North Korea, in addition to the various culture shocks experienced after entering South Korea. Not only stress relating to trauma and cultural differences they experience when they encounter South Korean culture, the stress they experience when they have to overcome prejudice and discrimination of South Korean society are also factors that hamper the normal development of North Korean adolescent refugees by threatening their physical and mental health [ 25]. According to a previous study, cultural adaptation stress, such as culture shock, discrimination, or sense of alienation, has a positive correlation with the aggression of North Korean adolescent refugees [ 14]. Therefore, North Korean adolescent refugees must have clear life goals in order to prevent cultural adaptation stress from leading to the externalization of aggression [ 14]. Moreover, as South Korea prefers the characteristics of a monoculture and lacks friendly feelings for North Korea as it is a divided nation, North Korean refugees are highly likely to experience prejudice and discrimination in South Korean society [ 26]. Therefore, there is a need to help them develop a coping strategy to efficiently cope with various conflicts caused from culture differences between South Korea and North Korea. In addition, there should be educational efforts to minimize cultural conflicts that occur at the school and community levels, creating opportunities for North Korean adolescent refugees and South Korean adolescents to participate together in event such as North Korean defecting adolescents’ competency enhancement program (HOPE) [ 1]. Programs in which North Korean adolescent refugees and South Korean adolescents can meet together will become a place of experience through which South Korean adolescents can learn a balanced view toward North Korea. This increase of mutual understanding can be promoted by encouraging North Korean adolescent refugees to actively participate. Second, emotional intelligence was found to have a significant direct effect on the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees. According to a study by Jeong [ 27], children having a higher emotional intelligence express and adjust their emotion appropriately according to the situation, and children having the ability to understand and consider others can adapt to people around them or different environments, which prevents behavioral problems. In a study by Lipnevich et al. [ 28], emotional intelligence improvement programs reduce aggressive behaviors of adolescents by improving their emotional awareness and management and empathizing ability, and help them to acquire socioemotional skills and improve their mental health. North Korean adolescent refugees are susceptible to various stresses and anxieties about the society they now live in and their future because they are embarrassed, depressed, and intimidated by the different situations they are now experiencing in South Korean society [ 3]. Indeed, there is a desperate need for programs to cultivate emotional intelligence to help them resolve stresses, various conflicts, and other emotional problems that they face. Because the ways to resolve problems in a healthy way are different depending on how they perceive, understand, and deal with those problems emotionally [ 29], such programs will help North Korean adolescent refugees control their emotions and sentiment appropriately, and allow them to maintain a stable and positive psychological state, enabling them to function socially and live a happy life. Lastly, although the direct effect of negative attitudes of parenting on the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees was not deemed to be significant, the negative attitude of parenting was found to affect emotional intelligence as a medium. This finding is in line with a study by Kim and Kang [ 30], which states that mothers’ attitude of parenting has an indirect effect on children’s adaptation in school life through emotional adjustment, and can be interpreted such that negative parenting attitudes negatively affect the emotional intelligence of North Korean adolescent refugees, which in turn negatively effects their psychosocial adjustment. Family is an important support resource for North Korean adolescent refugees. However, single-parent family and family disorganization, the family characteristics of North Korean adolescent refugees, usually lead to the abandonment of education, child abuse, or family neglect. The psychological confusion North Korean adolescent refugees experience when they decide to enter welfare facilities, reenter alternative schools, or choose other careers after failing to adapt in regular schools are examples showing that stable settlement at home is needed [ 16]. It also shows that the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees is fundamentally derived from a stable family and home life. Thus, there is a need for a democratic, warm, peaceful and positive attitude-not neglect, inconsistency, or abuse, as supported by the results research that confirms that attitude of parenting has a critical effect on the psychosocial development of children. In a study by Lee and Jeon [ 7], many fathers among North Korean refugees displayed a positive attitude of parenting, such as affection and encouragement, though over 30% of subjects needed clinical help due to high parenting stress. Since the attitude of parenting perceived by children can be different from the actual attitude of parenting, it is important how children perceive different experiences [ 6]. Hence, parents need to receive education along with their children to ensure their children’s positive growth and development and their family’s successful settlement in South Korean society. Again, although the negative attitude of parenting was not deemed to be a variable that directly affects psychosocial adjustment in this study, parents’ compassionate and democratic attitude of parenting is expected to have a positive effect on the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean refugees, by cultivating their emotional intelligence. This study has significance in that it constructed a model to explain the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees and suggested a direction for creating programs for psychosocial adjustment. However, these research results cannot be generalized because the subjects used in this study did not include all North Korean adolescent refugees and due to the fact that the attitude of parenting, as a research variable, was investigated only on adolescents. As such a follow-up study to investigate parents is also needed.

Also, although the model was constructed by selecting stresses and attitudes of parenting as variables that affect psychosocial adjustment, according to theoretical background and previous studies, there is a need for a follow-up study that verifies the variables that influence and effect adjustment, such as relationship with peers, school, and social support. In a study by Lee [ 18], the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees varied depending on gender, age, and presence of family; a follow-up study needs to compare the paths of the structural model of psychosocial adjustment according to general characteristics through an analysis of multiple groups. Furthermore, as research tools for adolescents are usually based adolescents aged to 18 or 19, for future research, the subject age of North Korean adolescent refugees should be divided to adolescents aged 19 or younger and early adults aged 20 or older. There is also a need to develop an instrument for North Korean adolescent refugees that secures validity and reliability of the results, which has been pointed out in various studies on North Korean adolescent refugees.

CONCLUSION

A stable settlement of North Korean adolescent refugees can be successfully made only when North Korean adolescent refugees overcome trauma they experience in North Korean life, in the process of escaping North Korea, and from culture shock they experience after entering South Korea based on sufficient support from family and society. This study tested the effects of stress and attitude of parenting on the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees based on the theory of stress and coping from Lazarus and Folkman [ 19]. As a result, the direct effect of stress and emotional intelligence on the psychosocial adjustment of North Korean adolescent refugees was deemed to be significant, with the negative attitude of parenting having an indirect effect on their emotional intelligence. Therefore, there is a need for active intervention to relieve post-traumatic and cultural adaptation stresses and to cultivate the emotional intelligence of North Korean adolescent refugees through education and the encouragement of positive attitudes of parenting. Through these results, communities and governmental agencies need to make efforts to help North Korean adolescent refugees grow as healthy members of our society by decreasing negative behaviors, such as shrinking, delinquency, and aggression, and to develop and apply various interventions to improve the psychosocial adjustments of North Korean adolescent refugees.

REFERENCES

1. Ministry of Education. 2017 Statistics of North Korean students. North Korean youth support center [Internet]. Seoul: Ministry of Education; 2018 [cited 2018 April 30]. Available from: https://www.hub4u.or.kr/hub/data/boardList.do

2. Kwak YJ. Effects of emotional intelligence program for adolescent. Korean Journal of Youth Studies. 2010;17(4):263-281.

3. Jeon JY. Mental health problems of children and adolescents from North Korea: Evaluation and treatment. 2011 April 29; Samsung Hospital. Seoul: Korean Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry; 2011. p. 137-139.

4. Sam D, Vedder P, Ward C, Horenczyk G. Psychological and sociocultural adaptation of immigrant youth In: Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P, editors. Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. 1st ed. Mahwah NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006. p. 117-141.

5. Kim JR. The effect of family violence exposure on school violence among adolescents: Mediating effects of life satisfaction, school life satisfaction, & internalizing. Korean Journal of Human Ecology. 2014;23(2):269-279. https://doi.org/10.5934/kjhe.2014.23.2.269

6. Kwon M. Comparison of child-rearing attitudes of parents and problem behavior of children as perceived by parents and children. Journal of Korean Academy of Child Health Nursing. 2009;15(2):164-170. https://doi.org/10.4094/jkachn.2009.15.2.164

8. Goleman D. Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ for character, health and lifelong achievement. 1st ed. New York: Bantam Books; 1995. p. 1-352.

9. Mikolajczak M, Menil C, Luminet O. Explaining the protective effect of trait emotional intelligence regarding occupational stress: Exploration of emotional labour processes. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(5):1107-1117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.01.003

10. Austin EJ, Saklofske DH, Egan V. Personality, well-being and health correlates of trait emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38(3):547-558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.009

12. Cho Y, Kim Y, Kim H. Influencing factors for problem behavior and PTSD of North Korean refugee youth. Korean Journal of Youth Studies. 2011;18(7):33-57.

13. Kim L, Park SH, Park KJ. Anxiety and depression of North Korean migrant youths: Effect of stress and social support. Korean Journal of Youth Studies. 2014;21(7):55-87.

14. Han N, Lee SY, Lee J. The differences of acculturation stress, everyday discrimination, social support from North/South Korean according to acculturation clusters of North Korean refugee youth in South Korea. Korean Journal of Social and Personality Psychology. 2017;31(2):77-100.

15. Kim YN. Youth support policy and service orientation for North Korean migrants in the civic-youth perspective. Korean Journal of Youth Studies. 2010;17(11):27-46.

16. Son GW, Choi SM, Kang DW, Oh JY. A survey on youth needs for North Korean degradation. Policy Research. Seoul: Ministry of Gender Equality and Family; 2016 March. Report No.: 160422.

17. Kim JH. A study on the factors affecting the psychosocial adaptation of North Korean youth refugees [master's thesis]. Seoul: Soongsil University; 2010. p. 1-70.

18. Lee IS Factors that influence juvenile North Korean defectors’ psychosocial adaptation to South Korea. 79th International conference on social science and humanities. 2017 October 6-7; Ours Inn Hankyu. Tokyo: ITAJ Publications. 2017. 32-35.

19. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. 1st ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. p. 22-52.

20. Woo JP. Concept and understanding of structural equation modeling. 1st. Seoul: Hannarae Publishing; 2012. p. 1-568.

21. Kim HC. Human relationships. 1st ed. Seoul: Education Science History; 2017. p. 1-332.

22. Kim YH, Kim HA, Cho YA, Kim YJ, Lee GR. A study on development of psychological and social adaptation evaluation tool for North Korean deviant youth. 1st ed. Seoul: Rainbow Youth Center; 2009. p. 1-73.

23. Moon Y. EQ is likely a higher success. 1st ed. Seoul: Gulirang; 1997. p. 1-196.

24. Oh K, Lee HR, Hong GE, Ha EH. Korean Youth Self Report (K-YSR). 1st ed. Seoul: Huno Consulting; 2007. p. 1-65.

25. Jung HJ. North Korean refugees’ emotionality and its social implications: A perspective from cultural psychology. Institute of Cultural Studies. 2005;11(1):81-111.

26. Lee IS. Factors affecting the attitudes of nursing college students toward North Korean refugees. Journal of Korean Academic Society of Home Care Nursing. 2017;24(1):44-51.

27. Jeong HH. Relationships between stress, emotional intelligence, and behavior problem by child's sex. The Korean Journal of Rehabilitation Psychology. 2009;16(2):53-73.

28. Lipnevich AA, MacCann C, Bertling JP, Naemi B, Roberts RD. Emotional reactions toward school situations: Relationships with academic outcomes. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2012;30(4):387-401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282912449445

29. Mikolajczak M, Menil C, Luminet O. Explaining the protective effect of trait emotional intelligence regarding occupational stress: Exploration of emotional labour processes. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(5):1107-1117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.01.003

30. Kim DG, Kang MS. The mediated effects on empathy in the relations between children's perception of maternal parenting and adaptation to school life of elementary school students. Journal of Educational Innovation Research. 2017;27(1):203-222. https://doi.org/10.21024/pnuedi.27.1.201703.203

Figure. 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

Figure. 2.

Effect analysis in the structural equation model.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables (N=290)

|

Variables |

Categories |

Minimum |

Maximum |

M±SD |

Range |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

CR |

AVE |

|

Attitude of parenting |

Neglect |

1.00 |

5.00 |

2.14±0.89 |

1~5 |

0.78 |

0.49 |

.79 |

.55 |

|

Inconsistency |

1.00 |

5.00 |

2.46±0.79 |

1~5 |

0.00 |

-0.20 |

|

|

|

Abuse |

1.00 |

5.00 |

2.16±0.94 |

1~5 |

0.90 |

0.70 |

|

|

|

Stress |

Post-traumatic stress |

1.00 |

3.74 |

1.84±0.59 |

1~4 |

0.64 |

0.02 |

.82 |

.69 |

|

Cultural adaptation |

1.00 |

4.06 |

2.38±0.72 |

1~5 |

-0.17 |

-0.33 |

|

|

|

Emotional intelligence |

Empathy |

2.00 |

5.00 |

3.44±0.50 |

1~5 |

0.13 |

0.42 |

.85 |

.66 |

|

Facilitation thinking |

2.29 |

4.86 |

3.57±0.47 |

1~5 |

-0.40 |

0.19 |

|

|

|

Using emotional knowledge |

2.00 |

5.00 |

3.64±0.54 |

1~5 |

-0.00 |

-0.06 |

|

|

|

Psychosocial adjustment |

Shrinking |

1.00 |

3.00 |

1.17±0.42 |

1~3 |

0.15 |

-0.60 |

.97 |

.91 |

|

Delinquency |

1.00 |

2.45 |

1.35±0.28 |

1~3 |

1.44 |

2.35 |

|

|

|

Aggression |

1.00 |

2.63 |

1.44±0.30 |

1~3 |

0.94 |

0.65 |

|

|

Table 2.

Correlation among the Major Variables (N=290)

|

Variables |

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

|

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

|

1. Neglect |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Inconsistency |

.50 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Abuse |

.49 (<.001) |

.52 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Post-traumatic stress symptom |

.30 (<.001) |

.32 (<.001) |

.38 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Cultural adaptation stress |

.28 (<.001) |

.34 (<.001) |

.39 (<.001) |

.48 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Empathy |

-.08 (.205) |

-.03 (.563) |

-.19 (.001) |

-.14 (.017) |

.07 (.263) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. Facilitation thinking |

-.25 (<.001) |

-.14 (.019) |

-.24 (<.001) |

-.21 (<.001) |

.05 (.394) |

.41 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

8. Using emotional knowledge |

-.05 (.392) |

-.02 (.789) |

.01 (.928) |

-.03 (.580) |

.13 (.022) |

.32 (<.001) |

.29 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

9. Shrinking |

.28 (<.001) |

.26 (<.001) |

.21 (<.001) |

.50 (<.001) |

.46 (<.001) |

-.03 (.601) |

-.02 (.732) |

-.06 (.281) |

1 |

|

|

|

10. Delinquency |

.36 (<.001) |

.25 (<.001) |

.39 (<.001) |

.40 (<.001) |

.39 (<.001) |

-.12 (.036) |

-.16 (.005) |

-.05 (.416) |

.46 (<.001) |

1 |

|

|

11. Aggression |

.32 (<.001) |

.22 (<.001) |

.40 (<.001) |

.45 (<.001) |

.36 (<.001) |

-.07 (.243) |

-.24 (<.001) |

-.02 (.779) |

.41 (<.001) |

.76 (<.001) |

1 |

Table 3.

Standardized Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects (N=290)

|

Endogenous variables |

Exogenous variables |

Standardized direct effect |

Standardized indirect effect |

Standardized total effect |

SMC |

|

Emotional intelligence |

Stress |

.24 (.253) |

- |

.24 (.253) |

.13 |

|

Attitude of parenting |

-.48 (.009) |

- |

-.48 (.009) |

|

|

Psychosocial adjustment |

Stress |

.64 (.009) |

-.03 (.136) |

.61 (.006) |

.50 |

|

Attitude of parenting |

.06 (.681) |

.06 (.028) |

.12 (.277) |

|

|

Emotional intelligence |

-.12 (.033) |

- |

-.12 (.033) |

|

|

|