Nursing students' rights in clinical practice in South Korea: a hybrid concept-analysis study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to derive a conceptual definition and attributes for nursing students' rights in clinical practice in South Korea.

Methods

This concept-analysis study was conducted at a nursing school in South Korea. The participants were recruited using purposive sampling. The inclusion criteria were being a fourth-year nursing student and having two or more semesters of practical experience. The hybrid model used in this study had three stages. First, 12 studies were reviewed during the theoretical stage. Second, 10 in-depth interviews were conducted during the fieldwork stage. Third, in the analytical stage, the concept of nursing students' rights related to clinical practice was defined and the attributes were derived.

Results

The analysis established five attributes of nursing students' rights: the right to learn, the right to be protected from infections and accidents, the right to be cared for and supported, the right to be respected, and the right to be recognized as a member of a nursing team. A key theme that emerged from this study was having the right to learn in a safe and supportive environment.

Conclusion

It is necessary to develop a measurement tool based on the above five attributes and to verify its effectiveness.

INTRODUCTION

A nursing student's rights in clinical practice refer to his or her rights as a student participating in clinical training. The rights of nursing students include the rights to study, be protected, be supported, and handle grievances [1,2]. Therefore, it is necessary to provide clinical education in a way that respects the rights of nursing students [2]. Clinical education in nursing prepares students to become nurses by providing opportunities to apply theory to clinical situations and acquire knowledge and skills [3-5]. Nursing students in clinical practice are often exposed to situations in which their human rights are violated, such as cases of discrimination and bullying. They may also receive verbal or physical abuse from medical staff and patients, be exposed to infection, or experience safety accidents [6-10]. However, nursing students tend not to assert their rights to safety [11].

For nursing students to receive safe, effective clinical training, it is necessary for them to be aware of their rights [2,11]. To evaluate the degree to which nursing students' rights are respected, a scale that can measure the concept must first be developed [2]. A literature review shows that previous studies on the rights of nursing students have not adequately addressed this topic, offered a concept analysis, or developed a measurement tool. Among previous studies about the clinical experiences of nursing students [3,4,6,8-11], some studies focused only on the learning aspect [3,4,9], some investigated only the incivility experienced by nursing students [6,8,10], and one study addressed coping experiences [11]. These studies are insufficient for understanding and measuring the rights of nursing students in clinical practice.

A previous study on nursing students' awareness of their rights in clinical practice reported that they felt isolated during practicum and did not assert their rights. The nursing students felt that a support system was needed to protect and advocate for nursing students [2]. That study is meaningful in that it qualitatively examined nursing students' rights in clinical practice. However, its theoretical analysis and results do not support the development of a measurement tool [12]. Taken together, the studies conducted to date have had limi-tations in developing a tool to measure the rights of nursing students in clinical practice.

The current study is a preliminary study that conducted a concept analysis to support the development of an instrument in the future. Hybrid concept analysis is a useful model for understanding concepts that combines theoretical and fieldwork approaches [12,13]. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to use a hybrid model to derive conceptual definitions and attributes for nursing students' rights in clinical practice. For this purpose, a literature review-based theoretical analysis was performed, along with an analysis of empirical data collected from clinical settings. This study provides basic data for developing a scale to measure the rights of nursing students, thereby contributing to improving the awareness of those rights in clinical practice.

METHODS

Ethics statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kunsan National University (No. 1040117-202006-HR-009-02). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

1. Study Design

This concept-analysis study used a hybrid model to derive a definition and attributes for nursing students' rights in clinical practice. The paper was prepared according to the 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups in the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) [14].

2. Participants

For the fieldwork stage, purposive sampling was used to recruit participants for interviews. Purposive sampling is a method of selecting potential subjects who can provide rich and diverse experiences related to research questions [15]. In-depth interviews were conducted among participants who satisfied the inclusion criteria for the fieldwork stage. The inclusion criteria were 1) consenting voluntarily to participate in interviews, and 2) being a fourth-year undergraduate nursing student with at least two semesters of clinical practice experience [9,16]. A total of 10 individuals participated.

3. Data Collection and Setting

The theoretical, fieldwork, and final analytical stages were conducted following Schwartz-Barcott and Kim's three-stage hybrid model of concept analysis [12].

The participants were informed that all research data would be encrypted and stored on a private computer and would be deleted after the study was published. The interviewees were students at the researchers' universities, and some of them were also enrolled in the researchers' classes, so the recruitment for interview participation was conducted after all semester classes and clinical practice were completed and credits were awarded. Each participant received a gift after the interview.

1) Theoretical stage

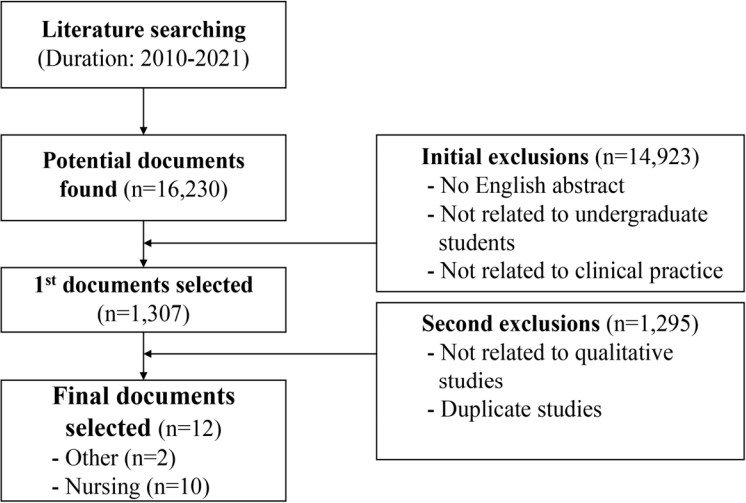

The keywords used for searching were "clinical practice," "rights," "experience," "nursing students," and "qualitative." During the initial screening, studies were excluded if there was no English abstract, if undergraduate students were not included, or if the study was not related to clinical practice. During the secondary screening, duplicate and non-qualitative studies were excluded. A total of 12 studies were finally selected (Figure 1).

2) Fieldwork stage

In this stage, a qualitative study was conducted using face-to-face in-depth interviews to explore participants' experiences. Data were collected from July 15 to August 30, 2021. Interviews were conducted in a comfortable and quiet place (e.g., cafe, seminar room) deemed suitable for speaking with the participants. The main questions were, "What do you think about the rights of nursing students during clinical practicum?" and "How was your experience of the rights of nursing students during your clinical practicum?" These semi-structured questions were asked to collect participants' experiences and thoughts. Since each interview was conducted freely at a time chosen by its participant, the duration varied to some extent; each interview lasted 60 to 80 minutes. After informed consent was obtained, the interviews were recorded with a tape recorder and field notes, then transcribed immediately afterwards to share the results among the researchers.

4. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using conventional content analysis [17]. First, the two researchers repeatedly reviewed the interview transcripts and extracted meaningful statements. Second, codes were produced by grouping interrelated statements. Third, the interrelated codes were grouped into subcategories, which were then grouped into final categories (attributes). Feedback on the research findings was requested from the participants.

5. Rigor

Research rigor was determined based on credibility, suitability, auditability, and verifiability [18]. For credibility, the researchers maintained neutral attitudes, avoided bracketing, and carefully listened to participants without interruption. To ensure suitability, the researchers extracted meaning from the participants' detailed descriptions of their experiences and collected data until it was saturated. To maintain auditability, the researchers and experts held feedback sessions to review whether the participants' statements were summarized in a way that retained their intentions. To maintain verifiability, the participants' statements were summarized, so that readers could verify the results.

RESULTS

1. Theoretical Stage

A total of 12 studies were selected, 10 from the field of nursing and two from other fields. A search of the available literature indicated that five key attributes of nursing students' rights included the right to learn, right to be protected from infections and accidents, right to receive care and support, right to be respected, and right to be recognized as a nursing team member. Each attribute had a set of subcategories (Table 1) [2-4,9,11,16,19-24], as follows. First, the right to learn refers to a right to the types of learning that nursing students can experience only in clinical practice [4]. Since nursing is a practice-based discipline, this means that nursing students must be able to learn clinical competence sufficiently [4,9,18]. Second, the right to be protected from infections and accidents means that nursing students must be protected from exposure to situations where safety or infection prevention measures cannot be maintained during the clinical practicum [2,25]. Third, the right to receive care and support indicates that nursing students should be supported and defended [2,18,19]. Fourth, the right to be respected means that nursing students should be respected while learning—not ignored, criticized, or discriminated against [2,6,19,25]. Fifth, the right to be recognized as a nursing team member refers to the right to be considered both a learner and a team member under the supervision of a clinical educator [9,16].

2. Fieldwork Stage

1) General characteristics of the participants

A total of 10 fourth-year nursing students from two universities in Jeonbuk and one university in Seoul participated in this study. Two students were male, and the rest were female. The participants' ages ranged from 21 to 27 years with a mean age of 23.40±1.84 years. They had three to four semesters of clinical experience (18-26 weeks) with a mean of 22.80 ±4.13 weeks.

2) Attributes of nursing students' rights in clinical practice identified at the fieldwork stage

A total of 41 meaningful codes were extracted from the in-depth interviews with the participants. Interrelated codes were grouped to produce 18 subcategories. Lastly, interrelated subcategories were grouped into five attributes, identical to those from the theoretical stage. Based on the interviews, the key attributes of nursing students' rights were the right to learn, right to be protected from infections and acci-dents, right to receive care and support, right to be respected, and right to be recognized as a nursing team member. Table 2 shows how the codes are grouped into subcategories and how the subcategories are grouped into attributes.

3. Final Analysis Stage

The five attributes identified in the theoretical stage were confirmed in the fieldwork stage, and the subcategories of each attribute were grouped identically. These attributes were identified by combining the results from the theoretical and fieldwork stages: the rights to learn, be protected from infections and accidents, receive care and support, be respected, and be recognized as a nursing team member (Table 3).

Based on the results of this analysis, the conceptual definition is as follows: nursing students' rights in clinical practice are the rights of students who practice nursing skills by applying theories they have learned to real tasks; these include the rights to manage tasks independently, assert their opinions, and make demands of others.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to analyze the concept and attributes of nursing students' rights in clinical education. The topic was selected because the important issue of the rights of nursing students during their clinical practicum has been overlooked. This study was structured according to a three-stage hybrid model. First, five attributes were identified through literature review during the theoretical stage, and then the same attributes were classified through in-depth interviews with nursing students. Because the attributes matched in these two stages, their labels were not changed during the final analytical stage.

In this study, the right to learn was confirmed as the first relevant aspect. It includes being encouraged and given opportunities to observe and engage in clinical practice, receiv-ing supervision and guidance on nursing skills, having the head nurse and other nurses participate in providing clinical education, and being provided with guidelines on systematic education. The National Student Nurses Association also grants the right to learn [1]. Students want a clinical education in which they can observe nursing procedures [2,5], are encouraged to engage actively in nursing procedures [3], and can practice necessary nursing skills under nurses' supervision [4,16]. Nursing students chose nurses as the most helpful people [20] and considered the supervision and education provided by nurses to be highly valuable [26].

Since nursing students view nurses as being able to provide them with clinical education and supervision, nurses must actively prepare for and participate in providing such clinical education. Students also reported that nursing managers should participate actively in clinical education [16] and provide students with guidelines [2], which is in line with the students' reports in the current study. Nursing students identified limited opportunities to learn or observe nursing procedures [2,9], a lack of clinical education guidelines [19], a lack of a systematic approach to clinical education, and inconsistent education between different clinical instructors [9] as the characteristics of poor education.

Students must be encouraged to observe nursing procedures, practice nursing skills, and be provided with a standardized education with systematic guidelines. Nurses and nurse managers must actively participate in providing clinical education, and nurse managers must try to provide students with systematic and standardized guidelines. Nurses must let students practice nursing skills themselves and give them as many opportunities to observe and engage in nursing procedures as possible. By engaging in this process, nurses can improve the learning rights of students in clinical practice.

The right to be protected from infections and accidents includes engaging in clinical practice in a safe environment, in which students are protected from infections and are provided with information about infected patients. Previous studies have also identified the right to engage in clinical practice in a safe environment, where students are protected from infections [2], and the right to learn in a safe environment [1], which are in line with the results of the current study.

However, students are rarely provided with information about infected patients [25] and are not protected from accidents [27], indicating a lack of information about infected patients and poor handling of accidents. Nursing students' right to health is violated when they are exposed to infections or accidents. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce a system that regularly checks hospital wards to focus on preventing infections and accidents. There must also be mandatory orientation sessions on the prevention and handling of infections and accidents before students start their clinical practicum.

The right to receive care and support includes being advocated for and encouraged, having one's grievances managed, working in a positive ward atmosphere, and being given care and support during clinical education. Previous studies have reported that nursing students need a clinical educational support system that protects and advocates for students [2], grievance-handling procedures [1], a positive atmosphere [3], support from clinical professors [7,27], and guidance and feedback from nurses who show interest in educating students [4,26], which are consistent with participants' reports in the current study. Meanwhile, nursing students also recog-nized nurses' negative attitudes and lack of support for students [9,19], an unsupportive ward atmosphere [19], lack of support and resources in hospitals [21], and lack of awareness of nursing students' rights [2,11] as poor clinical educational experiences. Therefore, efforts are needed to encourage students to receive clinical education in a positive and supportive environment. It is also necessary to explore a system to advocate for students when they receive unfair treatment.

The right to be respected includes not being discriminated against or bullied, not being ignored, and not being treated as someone who takes care of troublesome chores. Nursing students do not want to be ignored or discriminated against [2,19,22], or to be treated like a person who takes care of troublesome chores [9]. No one wants to work with someone who bullies or looks down on them. In the current study's in-depth interviews, students reported feeling respected when being addressed by respectful appellations instead of being spoken to disrespectfully. They also felt respected when they were asked to do a favor, instead of being commanded or ordered. The level of awareness of nursing students' rights should be assessed and continuously improved. A system should be in place to make nursing staff, patients, and caregivers aware of nursing students' rights, and to foster mutually respectful interactions.

The right to be recognized as a nursing team member includes being welcomed and introduced to the hospital staff, assisting with nursing tasks, having guaranteed meal and rest times, and being able to leave work on time. In previous studies, being officially introduced to the medical staff [3,16], be-ing appreciated for assisting nurses [4], having meals or rest time, and being allowed to leave work on time were reported as positive clinical experiences [2]. Recognizing nursing students as members of the nursing team is very unfamiliar in Korea. However, related studies have already been conducted abroad, and consistent results were obtained in this study as well. Nursing students have had the role of assisting nurses for a long time. Therefore, it will be necessary to have a system that delegates the duties of nurses to students so that students can engage in practice with a sense of belonging as members of the nursing team.

This study is meaningful in that, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first to conduct a concept analysis via a theoretical literature review and an analysis of empirical data from in-depth interviews, to gain an understanding of the concept of nursing students' rights in clinical practice. This study may contribute to improving the awareness of such rights and to the development of a measurement tool.

The educational implication of this study is that it provides empirical data on the rights of nursing students to practice safely. Based on the results of this study, it will be necessary to create a bill of rights for nursing students and guide them before their clinical training begins. The practical implication of this study is that it provides evidence regarding the need to improve the perception of nursing students' rights in hospitals. In addition, hospital officials should strive to ensure that nursing students' rights to learn are protected and an environment is guaranteed for safe practice.

One limitation of this study is that it was conducted among nursing students from specific regions. Therefore, the results might differ from the attributes of nursing students with different backgrounds. In addition, because the sample size of participants in the fieldwork stage was small, its representativeness cannot be guaranteed. Therefore, the results must be interpreted and generalized with caution. A third limitation is that at the theoretical stage, all included studies were limited to publications written in English or Korean.

Further research is needed to understand the application of the present attributes of nursing students' rights to nursing education and its direct impact on nursing students' outcomes. Furthermore, in clinical practicum contexts, there is a need to develop intervention programs that consider nursing students' rights and conduct research to prove their effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

Five attributes of nursing students' rights in clinical practice were derived: the rights to learn, be protected from infections and accidents, receive care and support, be respected, and be recognized as a nursing team member. The main theme derived from this study was the right to learn in a safe and supportive environment.

Nursing students want to be respected as students and to actively assist nurses with nursing tasks as members of a nursing team. They believe that hospitals and schools must devote more attention and support to providing them with systematic education, and that students' rights to engage in clinical practice in a safe environment must be protected. This study's clear division of nursing students' rights into five attributes will help to raise awareness of these rights in clinical education. Based on the results of this study, we suggest developing a scale that can measure how well nursing students' clinical practicum supports their rights.

Notes

Authors' contribution

Conceptualization: all authors; Data collection, Formal analysis: all authors; Writing-original draft: all authors; Writing-review and editing: all authors; Final approval of published version: all authors.

Conflict of interest

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Research Year of Chungbuk National University in 2021.

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

Acknowledgements

None.