The perceptions and performance of family-centered care among pediatric nurses at a children's hospital in South Korea: a descriptive study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to examine pediatric hospital nurses' perceptions and performance of family-centered care.

Methods

A descriptive study design was used. This study surveyed 162 nurses who worked at a single tertiary children's hospital in South Korea. The modified Family-Centered Care Scale was used to assess nurses' perceptions and performance of family-centered care. Barriers to the implementation of family-centered care were described in an open-ended format.

Results

Pediatric hospital nurses had a higher score for perceptions (mean score=4.07) than for performance (mean score=3.77). The collaboration subscale had the lowest scores for both perceptions and performance. The perceptions of family-centered care differed significantly according to the nurses’ clinical career in the pediatric unit and familiarity with family-centered care, while performance differed according to clinical career only. Perceptions and performance were positively correlated (r=.594, p<.001). Barriers to implementation included a shortage of nursing personnel, a lack of time, and the absence of a family-centered care system.

Conclusion

To improve the performance of family-centered care, nurses’ perceptions of family-centered care should be improved by offering education programs and active support, including sufficient staffing, and establishing systems within hospitals.

INTRODUCTION

Family is an important component of the environment for children's growth; a child's environment has a major influence on his or her development, and the unique experiences of children affect all family members. Therefore, planning for medical services or care for children should involve the entire family [1]. In recent years, interest in family-centered care has been increasing. Family-centered care refers to partnerships between healthcare professionals, patients, and families that are mutually beneficial and involve the planning, implementation, and evaluation of healthcare services. Family-centered care can provide optimal healthcare, improve nursing quality and safety, increase care satisfaction, and achieve better outcomes for patients and families [2].

Jung and Tak [3] defined family-centered care as recognizing families as experts on their children, acknowledging the values and diversity of families, respecting and supporting families, collaborating with families and healthcare professionals through partnership, and physically and emotionally supporting families to participate in care and share information between families and healthcare professionals. Therefore, family-centered care is a way to provide care and medical services to children and families in which care is planned with the entire family at the center and all family members are recognized as care recipients [4].

More specifically, the core concepts of family-centered care include participation, collaboration, information sharing, and dignity and respect. Participation refers to encouraging and supporting families to participate in treatment and decisionmaking [5]. Support is necessary for appropriate participation and includes supporting family decision-making and participation, responding to the needs of families for their children, and supporting children and families as they cope with anxiety and stress [6]. Collaboration refers, in addition to parents and nurses working together in the child's care process [7], to broader patterns of working together among families, healthcare providers, and healthcare leaders in policy development, program implementation, and evaluation [5]. Information sharing refers to delivering unbiased and adequate information to families that enables them to participate effectively in decision-making [5]. Dignity and respect involve listening to the opinions of family members, respecting the choices, knowledge, values, beliefs, and cultural backgrounds of patients and families, and including families in treatment plans [5,8]. Tools to measure family-centered care developed in Korea also include the areas of collaboration, family support, information sharing, and family respect [9].

Family-centered care is an important philosophy in pediatric nursing, and it plays a crucial role in the initial contact with the child and family during a child's hospitalization. The nurse who is the first point of contact with the family of the hospitalized child and closest to the child can quickly and accurately understand the needs and strengths of children and families as a healthcare professional and play a key role in the successful implementation of family-centered care [10,11].

In order for nurses to successfully apply family-centered care when caring for children and fulfill their role, it is first important to understand their existing perceptions of family-centered care and their performance of family-centered care.

Previous international studies have observed differences between the perceptions and performance of family-centered care among healthcare professionals. Studies have shown that scores for the performance of family-centered care tend to be lower than scores for perceptions [12-14]. Furthermore, differences in perceptions and performance have been observed across different sub-domains of family-centered care [12,13,15] as well as different demographic characteristics [16,17].

However, in Korea, family-centered care is still a relatively unfamiliar concept, and there is a lack of existing research on the topic. In South Korea, it is common for families to stay with their hospitalized children and actively participate in their care, leading to close interactions between pediatric nurses and families. However, the caregivers of hospitalized children tend to perceive nursing care to be inadequate in terms of meeting their stated needs [18].

To conduct further studies and devise interventions related to family-centered care, the perceptions and performance of family-centered care among nurses working in hospitals must be understood. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the perceptions and performance of family-centered care among nurses caring for children and to provide data that can be used as a basis for the further development of family-centered care.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the perceptions and performance of family-centered care among pediatric hospital nurses, with the following specific objectives: first, to assess the perceptions and performance of family-centered care among pediatric hospital nurses; second, to identify differences in the perceptions and performance of family-centered care according to the general characteristics of pediatric hospital nurses; third, to identify differences between the perceptions and performance of family-centered care among pediatric hospital nurses; and fourth, to identify barriers to the implementation of family-centered care among nurses at a children's hospital.

METHODS

Ethics statement: The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital (No. 2207-196-1345) reviewed this study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

1. Study Design

This descriptive study investigated the perceptions and performance of family-centered care among pediatric hospital nurses. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines [19].

2. Study Participants

The participants in this study were 162 nurses working at a single tertiary children's hospital located in Seoul, South Korea. The inclusion criteria for the study participants were nurses working in wards and intensive care units of the pediatric hospital who directly provided nursing care to patients. The exclusion criteria were nurses who worked in the emergency room, operating room, and outpatient departments; nurses who did not directly provide nursing care to patients; and head nurses, teaching nurses, and new nurses who had been hired within 8 weeks. The minimum sample size for the study was 159, calculated using G*Power 3.1.9based on an effect size of .25, power of .80, and significance level of .05 for the F-test in analysis of variance. The total number of participants in this study was 162, which satisfied the minimum sample size requirement.

3. Measurements

The perceptions and performance of family-centered care among pediatric hospital nurses were measured using a tool developed by Jung [9], which was modified to suit the purpose of this study. The family-centered care measurement tool developed by Jung [9] consists of a total of 29 items across four subscales: collaboration (12 items), family support (8 items), information sharing (3 items), and family respect (6 items). The original tool was developed to measure the perceptions of family-centered care among the family members of hospitalized children with "healthcare professionals" as the subject of the questionnaire items [9]. Permission was obtained from the tool's developer to modify the questionnaire items to use the first-person perspective, allowing the research participants, who were nurses, to be the subjects.

The modified Family-Centered Care measurement tool was used to measure both perceptions and performance of family-centered care. The tool used a 5-point Likert scale in this study to assess the importance of each item in terms of the nurses' perception, with responses ranging from 5 points (very important) to 1 point (not important). The performance score for each item was also measured on a 5-point scale with responses ranging from 5 points (always perform) to1 point (never perform). At the time of the original tool's development, the reliability indicated by Cronbach's alpha was .96. The reliability coefficients for each subscale were .94 for collaboration, .91 for family support, .87 for family respect, and .71 for information sharing. The questionnaire used in this study consisted of items on general characteristics, the perceptions of family-centered care, the performance of familycentered care, and open-ended questions. To identify barriers to the implementation of family-centered care, the following open-ended question was used: "In your opinion, what do you think are the barriers that impede the implementation of family-centered care?"

4. Data Collection

We received permission for data collection from the nursing department (data collection permit number: 2202_26). The researcher visited each ward and intensive care unit, explained the research purpose and data collection methods to the department managers, and distributed guidance about the research and the questionnaires. The questionnaire took approximately 10 to 15 minutes to complete, and the data collection period lasted from October 6, 2022, to November 4, 2022. Each nurse was informed about the study details and voluntarily agreed to participate. After consenting to participate in the study, the nurse completed the consent form and survey questionnaire, placed them in separate sealed envelopes to ensure data confidentiality, and submitted them to a randomly placed questionnaire collection box within the department. The submitted questionnaires were collected by the researcher in person during a departmental visit at the end of the data collection period. To provide a reward to the participants who completed the survey, their contact information was collected without their names to ensure anonymity and confidentiality, and each participant completed a consent form allowing the use of personal information as part of collecting contact information.

5.Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows (version 26.0; IBM Corp.).

· The participants' general characteristics and perceptions and performance of family-centered care were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations.

· The variables in this study were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Differences in perceptions and performance of family-centered care were analyzed based on the general characteristics of the study participants as follows. Differences in the perceptions of family-centered care, which did not satisfy the assumption of normality, were analyzed using non-parametric statistics, specifically the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test. Differences in the performance of family-centered care, which satisfied the assumption of normality, were analyzed using the t-test and one-way analysis of variance, followed by the Scheffé test for posthoc analysis if significant differences were found.

· The correlation between the perceptions and performance of family-centered care was analyzed using Pearson's correlation coefficient.

· The open-ended responses regarding on barriers to the implementation of family-centered care were categorized by opinions and measured for frequency.

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics of Participants

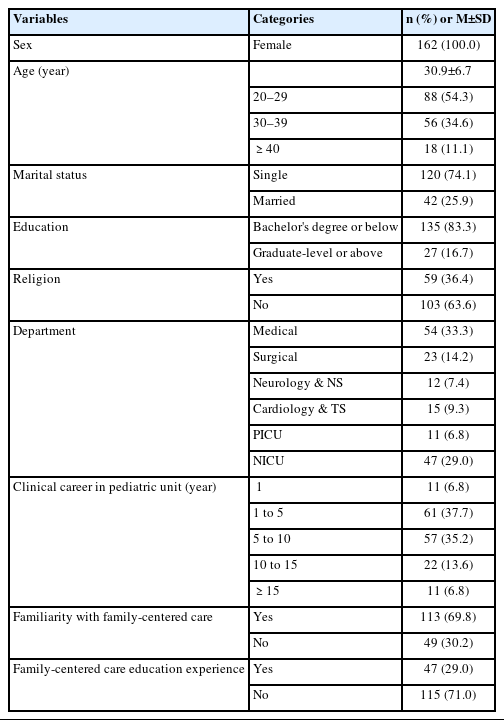

The study included a total of 162 participants. All were female, and the majority (88 participants, 54.3%) was aged 20 to 29 years, followed by those aged 30 to 39 years (56 participants, 34.6%). Most participants were unmarried (120 participants, 74.1%) and had a college or university degree (135 participants, 83.3%). There were more non-religious participants (103 participants, 63.6%) than religious participants (59 participants, 36.4%).

The current department of most of the participants was the internal medicine ward (54 participants, 33.3%), followed by the neonatal intensive care unit (47 participants, 29.0%). The most common length of clinical experience in the pediatric hospital was 1 to 5 years (61 participants, 37.7%).

A total of 113 participants (69.8%) responded that they had heard of family-centered care, and the majority (115 participants, 71.0%) reported that they had not received education on family-centered care (Table 1).

2. Scores for the Perceptions and Performance of Family-Centered Care

The perceptions and performance of family-centered care among pediatric hospital nurses were assessed in terms of overall average scores and the scores for four subscales: family respect, collaboration, information sharing, and family support.

The overall average score for the perceptions of family-centered care was 4.07±0.46 out of 5 points. Information sharing received the highest score among the subscales at 4.17±0.49 points, followed by family respect at 4.16±0.47 points, family support at 4.13±0.54 points, and collaboration at 3.97±0.48 points.

The results of the analysis of the performance of pediatric nurses in family-centered care are as follows. The average score for the performance of family-centered care was 3.77± 0.50 out of 5 points for all of the items. The performance scores for each of the subscales were 3.89±0.57 for family support, 3.88±0.54 for family respect, 3.83±0.58 for information sharing, and 3.61±0.56 for collaboration (Table 2).

3. Differences in the Perceptions and Performance of Family-Centered Care According to Participants' General Characteristics

The general characteristics that showed statistically significant differences according to perceptions of family-centered care were clinical career length in the pediatric unit (x2=13.67, p=.008) and familiarity with family-centered care (Z=-2.21, p=.027). The post-hoc test results for clinical career length in the pediatric unit showed that nurses with less than 1 year of experience had higher scores for their perceptions of family-centered care than those with 5 to 10 years of experience. Significant differences were found in the performance of family-centered care according to the clinical career length in the pediatric unit (F=2.56, p=.041) (Table 3).

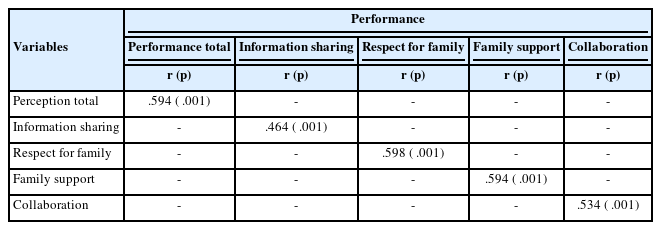

4. Correlations between the Perceptions and Performance of Family-Centered Care

A statistically significant positive correlation was noted between the total perception score and the total performance score (r=.594, p<.001) related to family-centered care. In addition, the information sharing (r=.464, p<.001), respect for family (r=.598, p<.001), family support (r=.594, p<.001), and collaboration (r=.534, p<.001) subscales showed statistically significant positive correlations between perceptions and performance (Table 4).

5. Opinions on Family-centered Care

1) The level of implementation of family-centered care

The level of implementation of family-centered care in the clinical setting was assessed among pediatric hospital nurses using a 5-point scale, and the mean score was 3.01±0.90 points. The most common score was 3 points for "sometimes implemented" (54 participants, 33.3%), followed by 4 points for "often implemented" (52 participants, 32.1%), 2 points for "sometimes implemented" (49 participants, 30.2%), 1 point for "almost never implemented" (4 participants, 2.5%), and 5 points for "always implemented" (3 participants, 1.9%).

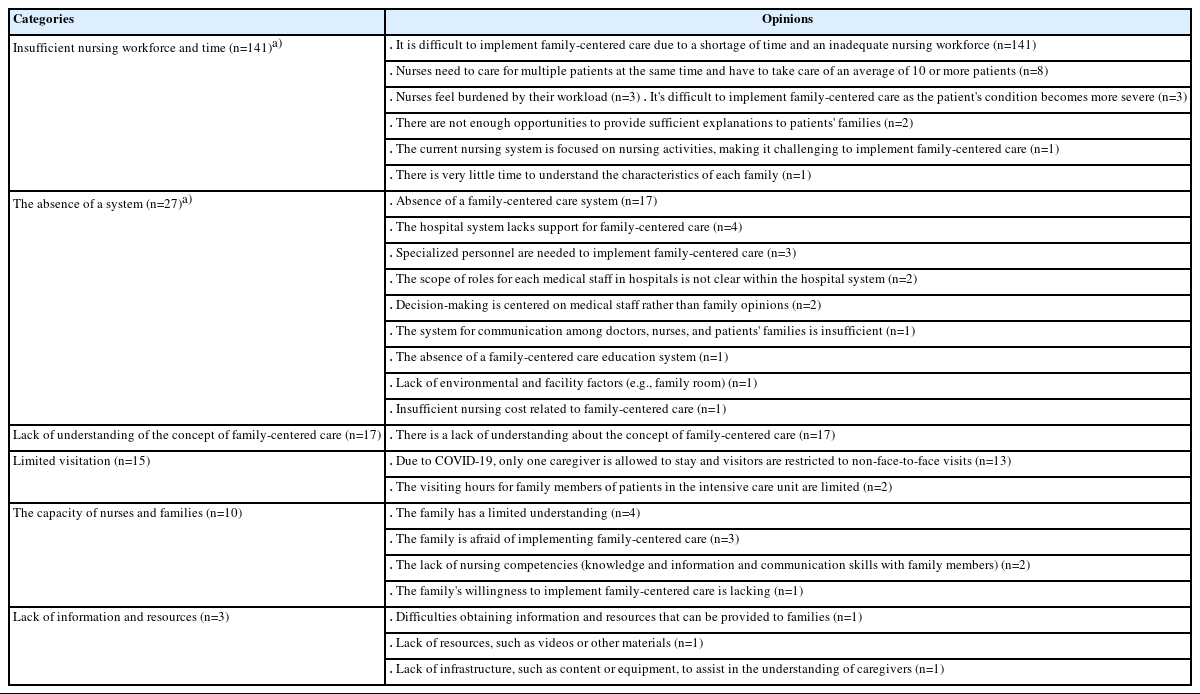

2) Barriers to family-centered care

The nurses were asked to freely describe which factors hindered the implementation of family-centered care, and the main factor was identified as an insufficient nursing workforce and time (n=141). The next most significant factors were the absence of a system (n=27), a lack of understanding of the concept of family-centered care (n=17), limited visitation (n=15), the capacity of nurses and families (n=10), and a lack of information and resources (n=3) (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to assess the perceptions and performance of family-centered care among pediatric hospital nurses. According to the study, the nurses' mean score for the perceptions of family-centered care was 4.07 out of 5 points, while their mean score for the performance of family-centered care was 3.77, indicating that nurses' perceptions of family-centered care were higher than their actual performance of it.

These findings are consistent with those of Bruce and Letourneau's study [12], which showed that healthcare professionals had higher perception scores related to family-centered care than performance scores. Although the measurement tools differed, other studies have also shown higher perception scores than performance scores [13]. In addition, a study that investigated the perceptions of family-centered care among nurses using the Family-Centered Care Questionnaire-Revised also found scores for the performance of family-centered care to be lower than the scores for the perceptions of family-centered care [14]. Although different measurement tools were used, both this study and previous studies have shown consistent results, indicating that nurses perceive family-centered care as important despite limitations in its actual implementation.

In this study, differences were found in the perceptions and performance of family-centered care across subscales. First, in terms of the perceptions of family-centered care, information sharing was perceived as the most important of the four subscales, while collaboration was perceived as less important.

In particular, the participants in this study recognized that providing information to families about the treatment, nursing, and disease of the patient is important in family-centered care. In a study by Prasopkittikun et al. [15], "providing emotional and financial support to the family" was also perceived as the most important domain in family-centered care. This includes providing information and support that helps families understand the disease process and the impact of a disease on the child and family.

In this study, collaboration was perceived as the least important of the four subscales. In particular, nurses had a low degree of awareness regarding discussing medical services or equipment with caregivers, talking about choices related to other medical services, and considering caregivers as equal partners instead of only parents of the patient. This is consistent with previous research results [13] that found the perception of collaboration to be the lowest. In another study, the scale that was perceived as the least important was collaboration between parents and professionals, and nurses believed that collaboration did not match current healthcare services. In other words, nurses consider themselves experts in care, and they are often unable to recognize family members as partners in the development, review, and implementation of treatment plans, the use of hospital facilities, and the application of policies [15]. It is important for nurses to recognize the need to collaborate with families when making treatment or healthcare-related decisions and to facilitate open communication even in the event of conflicting opinions with the family.

In this study, the performance of family-centered care was found to be the highest for family support and lowest for collaboration. Collaboration had the lowest scores for both perceptions and performance, indicating the lowest degree of recognition of its importance and the lowest degree of its performance. Bruce et al. [12] reported that healthcare providers showed the lowest degree of performance in terms of the design of healthcare delivery systems and parent/professional collaboration, which is consistent with the findings of this study. Other studies have also found collaboration [13] and the design of healthcare service delivery systems [15] to have the lowest family-centered care performance scores.

Within the area of collaboration, the performance of family-centered care was particularly low in terms of discussing and consulting with families about medical services, treatment, and care and informing them about other medical services. These behaviors require a partnership between nurses and families, the ability to see families as equal partners, knowledge, and a significant amount of time. In actual nursing practice, there is often a lack of time and resources to care for many patients while simultaneously engaging in discussions and consultations with their families.

Moreover, intensive care units where caregivers are not present continuously and visitation restrictions due to infectious diseases, such as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), make it even more challenging to engage in collaborative activity. The common perception that it is the role of physicians to determine the scope of treatment or care and to provide options for alternative medical services may be another reason for the lower rate of collaboration with patients' families.

A study [15] conducted in Thailand also showed the lowest degree of performance in the collaboration domain, suggesting that Thai patients and families have a respectful and passive attitude toward healthcare professionals, making it difficult for them to actively engage in collaboration. Furthermore, some nurses have stated that only parents with a higher education level can collaborate with healthcare professionals to make medical decisions, which may lead nurses to make decisions and provide care based on a care plan without collaborating with the patient's family [15].

In this study, both the perceptions and performance of family-centered care showed statistically significant differences according to the clinical career lengths of nurses in the pediatric unit. Subjects with less than 1 year of experience showed higher scores for the perceptions of family-centered care compared to those with 5 to 10 years of experience. Previous studies have shown that nurses with more experience working in pediatric departments have more positive perceptions of family-centered care [16,17]. While previous studies have shown a longer clinical career in pediatrics to be associated with higher scores for the perceptions of family-centered care, this study showed that subjects with under 1 year of experience had higher perception scores compared to those with 5 to 10 years of experience. This finding is not consistent with previous research. Further research is needed to investigate why nurses with under 1 year of experience perceived family-centered care to be more important than nurses with more experience.

The level of familiarity with family-centered care was found to be positively associated with perception scores. This suggests that education about family-centered care can enhance nurses' knowledge and perceptions of family-centered care, which can lead to better implementation in practice. Providing nurses with education on family-centered care can result in better outcomes when performing family-centered care as well as increase the degree of collaboration and support with families of hospitalized children.

In this study, insufficient nursing personnel and a lack of time were the largest barriers to implementing family-centered care. Nurses have to care for multiple patients simultaneously, which makes it difficult to implement family-centered care due to time restrictions. In previous studies, nursing workforce shortages led to overwhelming workloads for nurses, causing them to strictly prioritize resolving acute health issues related to patients' illnesses and health. As a result, the degree to which family-centered care was practiced, including meeting the other needs of patients' families, was inadequate [15]. In other studies, a high nurse-to-patient ratio was also recognized as a barrier to family-centered care [13], and healthcare personnel considered involving patients' parents in the treatment process to be difficult due to heavy workloads and a lack of time [20,21]. Therefore, in order to facilitate the implementation of family-centered care, the primary issue of nursing workforce shortages must be addressed.

This study revealed that the absence of a family-centered care system in hospitals was also a barrier to the implementation of family-centered care. A lack of systems, specialized personnel, and education for family-centered care were identified, and the roles of physicians and nurses are not always clear. Furthermore, physical and environmental factors related to family-centered care were also found to be inadequate, and pricing policies need to be established. To establish a system for the implementation of family-centered care, appropriate external resources must be provided, and education, payment, and compensation policies for family-centered care should be devised [22]. The physical environment, including spaces in which to practice family-centered care, must also be reimagined [23]. A lack of consideration from nurses toward family-centered care has been identified as a barrier [24]. Furthermore, to address these issues, it will be necessary to first establish a system and environment that is conducive to family-centered care, provide sufficient personnel and education to implement it effectively, and improve the perceptions and attitudes of nurses. In other words, it is necessary to establish a system that clarifies the roles of doctors and nurses, facilitates effective communication between healthcare providers and families, and provides infrastructure, facilities, and equipment, including spaces where family-centered care can be performed. In addition, the establishment of a supervisory system and appropriate remuneration could enhance nurses' competence and motivation related to family-centered care.

In this study, COVID-19 restrictions, including allowing only one caregiver to visit patients at a time, restrictions to visits, and the use of non-face-to-face communication methods, have made it difficult for nurses to communicate with families, hindering the implementation of family-centered care. In previous studies, COVID-19-related restrictions to family visits and gatherings, as well as the absence of family members, had an impact on family-centered care. These limitations have made it challenging to adequately understand the conditions of patients and meet the needs and requirements of both patients and their families [25,26].

A lack of competence regarding family-centered care among nurses and family members was also identified as a barrier to its implementation. Previous studies have reported difficulty implementing family-centered care due to the unfamiliarity of nurses with family-centered care and poor sophisticated communication skills [13,14]. The concerns of family members about their ability to participate in family-centered care, as well as their lack of understanding of medical terminology, treatments, and procedures, are also barriers [15]. Families may feel anxious about taking on roles traditionally performed by healthcare professionals in the hospital setting. Therefore, families must be provided with education and ongoing support related to family-centered care to alleviate their concerns. Healthcare professionals should not only assist families in understanding treatments and procedures but also provide support for families to develop their caregiving competencies. Furthermore, education and training programs should be developed and implemented to improve nurses' competencies.

The limitations of this study are as follows. The study used convenience sampling to recruit nursing personnel from a children's hospital at a single university as the study subjects, which limits the generalizability of the research results. Since the performance of family-centered care was assessed through a self-reported questionnaire, the results might differ from directly observed and measured data. In addition, this study was conducted at an unusual time during which only one caregiver was allowed to stay with each patient in the hospital due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the visitation policy was much more restrictive than usual. Despite these limitations, this study is noteworthy since it identified the perceptions and performance of family-centered care among pediatric nurses, analyzed the discrepancies between their perceptions and performance of family-centered care, and identified barriers to the implementation of family-centered care. This study provides foundational data for the development of interventions and educational programs aimed at improving the perceptions and performance of family-centered care among nurses.

CONCLUSION

This study examined the perceptions and performance of family-centered care of 162 nurses working at a tertiary children's hospital located in Seoul, South Korea.

The research findings revealed that the perceptions of family-centered care among nurses were higher than their actual performance of family-centered care in a children's hospital setting. The collaboration domain had the lowest scores for both perceptions and performance, indicating that nurses perceived collaboration to be relatively unimportant and were relatively unlikely to engage collaboratively in their performance of family-centered care.

Nurses with longer clinical careers in the pediatric unit showed higher scores for both the perceptions and performance of family-centered care, and those who were aware of family-centered care scored high for perceptions. Thus, there is a need for further education on family-centered care targeting nurses in Korea. In this study, the most significant barriers to the implementation of family-centered care were identified as a shortage of nursing personnel and limited time. Therefore, to encourage the performance of family-centered care, it will be crucial to establish systems and environments that support this approach and to provide adequate staffing and education to improve nurses' attitudes and perceptions. The findings of this study are expected to serve as foundational data for developing interventions and educational programs aimed at improving the perceptions and performance of family-centered care in the future.

Notes

Authors' contribution

Conceptualization: all authors; Data collection, Formal analysis: Suk-Jin Lim; Writing-original draft: all authors; Writingreview and editing: all authors; Final approval of published version: all authors.

Conflict of interest

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

Acknowledgements

None.