Analysis of court rulings on involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence by pediatric nurses: a systematic content analysis study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study systematically analyzed cases in South Korea wherein nurses were prosecuted for involuntary manslaughter or injury due to professional negligence in pediatric care.

Methods

We analyzed the precedents using the methodology of Hall and Wright (2008) and Austin (2010). Of the 618 cases retrieved from the Supreme Court Decisions Retrieval System in South Korea, we selected the 12 cases in which children were the victims and nurses were the defendants, using a case screening methodology.

Results

The most frequent penalty was a fine, and newborns were the most frequent victims. The distribution of cases according to Austin's violation categories was: improper administration of medications (n=5), failure to monitor for and report deterioration (n=4), ineffective communication (n=4), failure to delegate responsibly (n=4), failure to know and follow facility policies and procedures (n=1), and improper use of equipment (n=1).

Conclusion

To ensure the safety of children, nurses are required to teach and practice a high standard of care. Nursing education programs must improve nurses’ awareness of their legal obligations. Nursing organizations and leaders should also work towards enacting effective nursing laws and ensuring that nurses are aware of their legal rights and responsibilities.

INTRODUCTION

The expanding trend of specialization in the healthcare environment is causing a process of segmentation, triggering shifts in nurses’ roles and making nursing complex more complex and diversified [1]. As professionals, nurses have a legal duty of care for people under their responsibility according to their specific nursing role and status [2].

Nurses are held legally liable in cases of nursing-related accidents that cause harm to a patient. This may be in the form of criminal liability (leading to criminal punishment), civil liability (leading to compensation for damages), and/or administrative liability (leading to suspension of a license or work suspension)[3]. Despite the opinion that the scope of nurses’ duties was specified in the 2015 amendment of the Medical Service Act [4], the scope of nurses’ duties remains unclear, and the legal liability in cases of medical accidents is ambiguous and confusing when appraising unlicensed medical practices [5]. In addition, there are still problems with the unspecified scope and responsibility of various specialty nurses (e.g., perfusionists) for tasks that require independent and high-level professionalism [6]. Medical lawsuits against nurses are increasing due to these unstable legal and institutional guidelines, as well as the growing awareness of patients’ rights among healthcare service consumers [7].

Nursing care is required by vulnerable groups such as the elderly and children. In Korea, the elderly population is increasing and the population share of children is decreasing, with the number of children under the age of 14 drastically decreasing from 9.9 million in 2000 to 6.3 million in 2020 [8]. In this time of radical demographic change, the medical and nursing care of children and adolescents is different from that of adults. Pediatric patients have difficulty accurately describing the symptoms of their physical conditions as compared to adults; therefore, medical practitioners treating children must be able to observe carefully [9]. In addition to children’s potential inability children to sufficiently express their opinions and make decisions, the caregivers of children are also involved in providing information and decision-making, often resulting in delayed diagnosis and untimely or suboptimal treatment [10]. An important criterion for judging nursing errors is whether or not the responsible nurses neglected their duty of care as professionals. This point requires particular attention from pediatric nurses. Due to their developmental characteristics, children and adolescents are susceptible to serious diseases or accidents with consequences for their future growth and development, which can then lead to social costs and problems as well as personal costs [11].

The most common illegal act in nursing practice is negligence. Nursing education must strengthen legal awareness and help to prevent legal negligence by developing programs that present legal cases and other relevant statistics of clinical practice [12,13]. We found no fact-finding surveys related to the occurrence or prevention of legal problems among pediatric nurses in Korea. Therefore this study aimed to systematically analyze the cases in which Korean nurses were prosecuted and sentenced for involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence in pediatric care. The findings can also serve as basic data for developing educational programs designed to strengthen professional nurses’ legal and ethical competencies.

In this study, we sought to analyze the case law of involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury by nurses caring for children, examine the court rulings, and review the context and types of nursing practice. The results of this study can be used as basic data for creating standards to prevent nursing errors in pediatric care.

METHODS

Ethics statement: This study was approved by the institutional review board of Gangneung-Wonju National University (No. GWNUIRB-2021-38).

1. Research Design

This systematic content analysis study was conducted with the objectives of 1) systematically collecting cases of involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence by nurses, in which children were the victims, to understand the related situation and characteristics, 2) identifying the circumstances of the violations of legal nursing duties, and 3) determining the characteristics of involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence by pediatric nurses.

2. Research Method

A literature review was performed to systematically analyze the contents of criminal cases of involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence in which children were the victims and nurses were the suspects. We used the inductive content analysis method proposed by Hall and Wright [14]. This method was proposed in 2008 when legal case analysis was emerging as a type of technical content analysis in the social sciences, enabling lawyers to read and analyze legal decisions more systematically through a series of coded cases [14]. This methodology has led to an enhanced understanding of case law and an improved ability to evaluate unique cases in their legal context. This method was chosen because it enables consistent and systematic analyses of the collected precedents of cases involving nurses caring for children. The content analysis was conducted in three steps: 1) selecting cases, 2) coding cases, and 3) analyzing the case coding.

3. Literature Search

The study cases included the rulings of district courts, high courts, and the Supreme Court on criminal trial cases of involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professionally negligent pediatric nursing care that were adjudicated from 2000 to 2020. For the case search, we used the Supreme Court General Law Information Portal (online system), Supreme Court Decisions Retrieval System (online system), LAWnB (online system and paid service), and Case Notes (online system and free service), using the keywords.

4. Data Collection and Selection Process

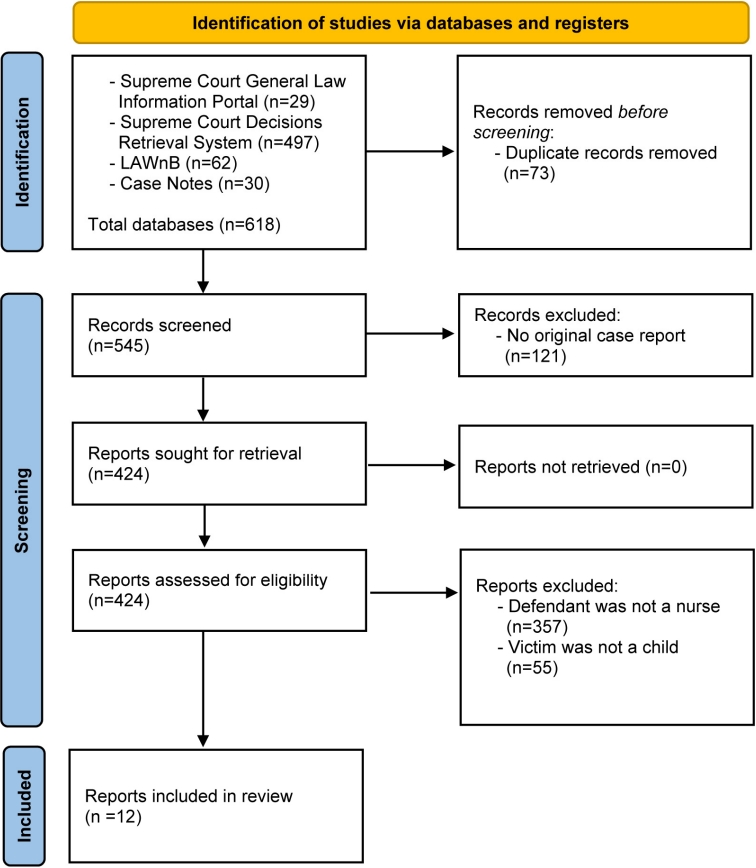

The data collection period was from August 1, 2020, to August 30, 2020. Using the keywords “nurse”, “involuntary manslaughter”, “professional negligence leading to death”, “professional negligence leading to injury”, “criminal case”, “newborns”, and “children and adolescents”, we retrieved 29 cases from the Supreme Court General Law Information Portal, 497 cases from the Supreme Court Decisions Retrieval System, 62 cases from LAWnB, and 30 cases from Case Notes. We requested permission from each court to access the case records and received files with anonymized court rulings by email. After removing duplicates (n=73) and records with no original case reports (n=121), 424 cases were reviewed. Next, 357 cases in which the defendants were not nurses and 55 cases in which the victims were not children were excluded. Twelve cases remained that involved involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence by pediatric nurses. Figure 1 shows the literature search process.

5. Data Analysis

To identify the characteristics of the court rulings on involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence by pediatric nurses, we extracted information on case number, the type of violation according to Austin’s classification, charge, disposition, a brief summary, Tatbestand for nursing negligence (breach of duty of care, outcome, causation), illegality, liability, and foreseeability into an Excel spreadsheet. Additionally, we classified the nursing activities eligible for legal protection into seven categories as proposed in Austin’s standard classification [15] of legal tips for nursing practice: a) administer medications properly, b) monitor for and report deterioration, c) communicate effectively, d) delegate responsibly, e) document in an accurate and timely manner, f) know and follow facility policies and procedures, and g) use equipment properly. We then searched for cases that did not follow or violated these legal standards [15].

Next, we focused on the requirements for the crime of involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence; that is, the constituent elements of the crime (hereinafter the “Tatbestand”) consisting of 1) illegal activities (breach of duty of care), 2) its harmful outcome (outcome), and 3) the causal connection (causation) between the first two elements. Tatbestand is a German word adopted in English and widely used in legal contexts. Article 14 of the Criminal Act defines “negligence” as an “act performed through ignorance of the facts which comprise the constituents of a crime by the neglect of normal attention” [11]. That is, negligence is an involuntary act constituting a crime [11]. A punishable crime that causes a result consistent with the Tatbestand by violating the duty of care is a crime of negligence. For the Tatbestand to be established, there must be evidence of an illegal act, a harmful outcome, and a causal connection between the act and the outcome [11]. We examined the cases of involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence, in which the victims were children, to identify the Tatbestand (i.e., breach of duty of care, confirmation of harmful consequences, and causal connection). We also investigated whether the Tatbestand was associated with the duties of foreseeability, illegality, liability, and avoidability.

6. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted after receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Gangneung-Wonju National University located in Wonju, Korea (No. GWNUIRB2021-38). The court rulings, which are the subjects of this study, are all documents open to the public. All documents were anonymized by the court, which precluded the collection of personal information. Accordingly, with a minimal risk level (level I), this study was exempted from the requirement to obtain consent from the subjects.

RESULTS

1. Selecting Cases

The 12 court rulings consisted of 10 district court decisions, 1 high court decision, and 1 Supreme Court decision. The highest frequency of incidents was found from 2005 to 2009 (n=7, 58.5%). Nurses were the sole defendants in six cases (50.0%) and doctors were accomplices in six cases (50.0%). Seven cases (58.3%) involved the crime of involuntary manslaughter (two cases were excluded as the high court and Supreme Court also ruled on the same cases) and five cases (41.7%) of professional negligence resulting in injury. The most frequent penalty imposed on nurses was a fine (n=8, 58.3%), and newborns were the most frequent victims (n=7, 58.3%) (Table 1).

2. Coding Cases and Analysis

For involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence to meet the requirements for a crime, the act of nursing negligence should satisfy the Tatbestand for a crime of negligence and be accompanied by illegality and liability. We classified the nursing activities eligible for legal protection into seven categories as proposed by Austin’s standard classification of legal tips for nursing practice [15]: 1) administer medications properly, 2) monitor for and report deterioration, 3) communicate effectively, 4) delegate responsibly, 5) document in an accurate and timely manner, 6) know and follow facility policies and procedures, and 7) use equipment properly, and then searched for cases that did not follow or violated the legal standards. The case numbers and details of the cases are shown in Table 2. Twelve cases were coded and analyzed, but only 10 cases were included in the content analysis because Case 9 included precedents from the first trial, the second trial, and the Supreme Court.

1) Failure to administer medications properly

Administering injections is a typical activity delegated to nurses and is a medical task within the scope of their clinical practice, whereas diagnosis and treatment are the tasks of doctors. Doctors prescribe the injection, but nurses perform the rest of the injection process, from preparing the injection agent to administering the injection itself. In principle, this can be interpreted as meaning that the work is to be done by a doctor, but a nurse can do it when required by the situation [3]. In Case 1, a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) nurse who was responsible for accurate medication administration and medication management (according to medication management guidelines), dispensed SMOFlipid (a lipid nutrient) in a place accessible to many hospital employees, rather than in an aseptic environment, and the injection was administered by a different person. In addition, although SMOFlipid was to be used for one person, it was dispensed into multiple-use doses, and the nurse, violating the instruction to use it immediately after opening it, left it at room temperature for more than 5 hours before administering it. As a result, the nurse was convicted of involuntary manslaughter.

In Case 3, a pediatric nurse had the professional duty of care to inject the prescribed antibiotic only after confirming that the patient showed no reaction to the antibiotic skin test. Nevertheless, the nurse did not pay attention to the information transmitted to her that the skin test result for the antibiotic (cefotaxime) was positive and administered an intravenous (IV) injection, causing anaphylactic shock that led to the death of a 2-year-old boy who had been hospitalized with laryngitis. In Case 5, a nurse working in the pediatric department was using scissors to remove a band-aid attached to the infusion needle on the right hand of a 6-month-old infant hospitalized with a high fever. The nurse had the professional duty of care to take measures to prevent injuries from the scissor blade, even if the victim moved his hand when freed from the band-aid, by making sure that the blade of the scissors would not touch the hand. As a result of neglecting this duty, the nurse was convicted of involuntary manslaughter.

Case 9 involves a failure to provide follow-up observation after administering valium, a high-risk medication. The patient was transferred to a tertiary hospital for treatment, where he died. In Case 10, a 14-month-old girl with respiratory distress symptoms due to pneumonia and asthma died due to a failure to conduct proper testing and administer timely therapy such as mechanical ventilation, even though inhalation therapy and drug treatment with epinephrine/aminophylline were found to be ineffective. In this case, apart from the doctor’s inappropriate treatment approaches, the nurse was also prosecuted and convicted for a breach of duty of care by not observing and reporting on the patient with respiratory distress.

Nursing behaviors classified as errors in medication administration were primarily cases in which the correct administration method was not followed or side effects related to a specific drug were not identified. However, Case 5, in which an accident occurred when the needle was removed, was also categorized as a dosing error.

2) Failure to monitor for and report deterioration

The second category of nursing error is a lack or delay in monitoring and reporting. A nurse’s duty of care to provide follow-up observation is regarded as an overlap of dependent and independent nursing activities. Dependent nursing activities are those that require a doctor’s instructions and supervision and the doctor’s instructions are an essential element of the work [3]. As presented in the first error classification,

Cases 3 and 5 were also cases where quick monitoring and reporting were omitted. Case 7 involved involuntary manslaughter due to professional negligence. A neonatal room nurse, was taking care of 12 newborns entrusted to the postpartum care center and 6 newborns admitted to the obstetrics and gynecology department at the same time. A breach of the nurse’s duty of care resulted in the suffocation of one newborn due to airway obstruction because the nurse neglected to observe for vomiting after feeding or to check for other abnormalities.

In Case 8, a nurse working in a postpartum care center was fined 3,000,000 won (2,500 USD) for involuntary manslaughter leading to the death of a newborn from suffocation due to airway obstruction caused by inhaling vomit. The nurse had tried to stop the newborn (26 days old) from crying heavily by increasing the feeding interval to 20 minutes. The nurse should have known that close feeding intervals are likely to trigger regurgitation of the upper-layer substances in the stomach. The additional feeding, as well as the weak digestion of a newborn, increases the likelihood of vomiting, which may obstruct the airway and lead to suffocation. The nurse’s duty of care to take measures against incessant crying by finding out its cause while controlling the volume of feeding was neglected.

Nursing errors in reporting and monitoring generally involved cases where the time to report an emergency to the doctor was delayed. The emergency was either not recognized instantly or the emergency was perceived or confirmed but reporting was delayed, both situations leading to fatal outcomes for the patient. In addition, there were two neonatal room cases in which dangerous situations led to post-feeding suffocation, but the incidents were not immediately recognized or confirmed even after the death of the child.

3) Failure to communicate effectively

The third type of nursing error is a lack of effective communication. Communication is a very important intervention in nursing care settings. Communication between medical teams, as well as communication with patients and caregivers, is important for effectively carrying out nursing activities [15]. The following cases are examples of insufficient communication.

In Case 1, a nurse in the NICU arbitrarily administered SMOFlipid twice without confirming the doctor’s unclear prescription. The head nurse working in the NICU was also liable for neglecting or condoning the dispensation of the liquid nutrient into multiple-use doses, as well as the delayed administration practice of the nurses. The head nurse did not provide proper education for the staff nurses on managing medication in a way that prevents infection, preparing injection agents, and on taking proper sanitation and infection measures. Education was also insufficient on properly reporting infection observation results transmitted from the infection management unit, or on preventing recurrence of medication errors.

In Case 3, proper shift-change communication did not take place. The nurse who took over received a note that the patient showed a positive skin reaction test to the antibiotic (cefotaxime), but she did not notice it, and this resulted in the anaphylactic shock and death of a 2-year-old child.

The nurse in Case 6 did not notice the report given by the caregiver and did not report it to the attending physician for 7 minutes, even though the nurse confirmed that the heart rate and oxygen saturation were abnormal. Due to this communication error, the patient did not receive emergency measures to secure the airway, which resulted in grade 1 encephalopathy.

In Case 10, the failure to communicate the ineffective inhalation therapy and drug treatments (epinephrine/aminophylline) and failure to suggest an alternative measure for airway maintenance can be considered an error of insufficient communication.

4) Delegate responsibly

To meet patients’ needs, nurses with appropriate skills and abilities should be able to delegate work appropriately to a co-worker. Accurate judgment regarding the right person to perform the work, the right type of work, in the right environment, with the right direction and the right supervision, is important for performing safe nursing [15].

In Case 2, the newborn's bath or hygiene could have been delegated to a nursing assistant or caregiver, but the nurse, who had the authority to delegate, did not do so and caused a fracture by dropping the newborn.

The nurse in Case 6 did not delegate tasks or provide instructions to the child's mother in a situation where the nurse could not directly observe the child for vomiting or other symptoms after administering antipyretics. The nurses in Cases 9 and 10 did not provide appropriate instructions or supervision for parents and neglected to observe or respond quickly to the side effects and subsequent symptoms of dangerous drugs administered to their children in the emergency room.

5) Failure to know and follow facility policies and procedures

The NICU nurse in Case 1 was responsible for accurate medication administration and medication management according to the hospital’s medication management guidelines. However, regarding the additional dose of SMOFlipid, she did not confirm the unclear prescription with the doctor and arbitrarily administered the injection twice. The nurse also dispensed this lipid nutrient into multiple-use doses in a room accessible by many hospital employees, not in an aseptic environment, and the injection was given by a nurse other than the nurse who prepared it. In addition, although the SMOFlipid was to be used for one person, it was dispensed into multiple-use doses, and the nurse, violating the instruction to use it immediately after opening it, left it at room temperature for more than 5 hours before administering it. As a result, the nurse was convicted of involuntary manslaughter.

6) Failure to use equipment properly

In Case 4, to prevent accidents in advance, an obstetrics and gynecology nurse had the professional duty of care, as an assistant to a natural delivery procedure, to check all measures for the safety of the newborn before participating in the childbirth. She neglected this duty of care and inflicted second- and third-degree burns to a newborn on the left shoulder blade, trunk, and lower limbs for an unknown number of treatment days by laying the newborn on an electric hot pack placed in the newborn cradle. Although interventions to maintain a newborn’s body temperature are an important and urgent part of nursing practice, the nursing error in this case lay in the failure to use an electric device (hot pack) efficiently and safely.

DISCUSSION

This study presents the results of a systematic review of court cases adjudicated as involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence.

Over the past two decades in Korea, there have been 12 cases of involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence by pediatric nurses, of which 10 cases were first instance (district court) cases, and two cases were appealed (one at a high court and one at the Supreme Court). The highest frequency of incidents occurred from 2005 to 2009 (n=7, 58.5%). Nurses were the sole defendants in six cases (50.0%, excluding the two overlapping cases). Seven cases (58.3%) involved the crime of involuntary manslaughter (excluding the two overlapping cases). Involuntary manslaughter cases outnumbered at-fault injury cases. Newborns represented the highest proportion of the victims.

As the field of nursing expands, along with increasing segmentation among healthcare services, the number of tasks that involve risk also increases. The increased risk of medical accidents related to nursing activities is demonstrated by the increasing number of court cases holding nurses liable for negligence, along with cases in which nurses are sole defendants [1]. Despite the increasing number of cases holding nurses liable for negligence, the standards for the scope or limit of legal liability for nursing are not well defined under the current law [1]. It is therefore necessary to identify the court rulings handed down thus far and to continuously raise issues about cases adjudicated by inaccurate legal standards.

Involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence by pediatric nurses was recognized in all but one of 12 cases. In the analysis of medical malpractice civil litigations, in which children and adolescents were the victims, 94.9% of the defendants lost the case due to a breach of duty of care [10].

Classifying the 12 cases in the present study according to Austin’s standard classification of the seven types of error [15] in terms of legal defense, five cases were prosecuted for inaccurate medication administration. The Korean Medical Service Act stipulates that injections are performed by medical assistants, who are registered nurses [18]. However, according to the precedents for standard of care regarding medication, intramuscular injections and intravenous injections can be performed without the presence of a doctor as per a doctor's prescription, high-risk injections such as intravascular potassium chloride should be injected in a doctor’s presence, and arterial injections must be performed by a physician [19]. Also, in a case of shock death due to a streptomycin injection in 1987 (Supreme Court Decision 86Daka1469, handed down on January 20, 1987), when a tuberculosis patient presented a prescription for a streptomycin injection issued from the community health clinic and asked the community health center to administer the injection, the community center confirmed a negative skin reaction test result and administered the streptomycin intramuscularly. A few hours later, the patient was found dead behind the community health center building. In this case, even with the negative skin test result, the community health center was held liable for negligence by not taking pre-preparation measures for shock prevention and stabilization and not providing follow-up observation of the patient’s post-injection condition [1]. However, this ruling held that the lower court’s decision that there was serious negligence by requiring a medical knowledge level based on a general physician’s level of knowledge misunderstood the legal principle of medical negligence. In Case 3 of our study, the victim was a child who required special attention due to anatomical and physiological vulnerability. When a positive skin test result was confirmed after an antibiotic was prescribed, the medication prescription should have been immediately canceled and a new antibiotic should have been prescribed. Even if the skin test result had been negative, the medical team should have been prepared for an emergency and monitored the post-injection condition for a certain period. Various accident prevention systems are employed in hospitals. The most widely used strategy is based on the electronic medical record (EMR). In this case, if the nurse who confirmed the previous antibiotic skin test had immediately marked it on the EMR and the drug for which the positive reaction was confirmed had been removed from the prescription or marked in red to warn of the risk, the nurse would not have administered the medication as originally prescribed. Medication administration falls within the scope of nurses’ clinical practice. Considering the current clinical practice that doctors prescribe drugs and nurses administer them, medication administration is an act requiring special attention. Based on the Nursing Practice Standard, the administration of medication by nurses includes confirming whether the drug is the same as the one prescribed; the patient is the correct recipient of the medication; the dose, medication time, and administration method are correct; there is written confirmation of oral prescription orders; and inaccurate or incomplete prescriptions are questioned and administration is withheld until questions are resolved [20]. In particular, pediatric nurses should be able to accurately perform medication administration in compliance with these medication administration care standards.

The second type of error is patient harm due to negligent monitoring and a delay in reporting. The duty of follow-up observation is an overlap of dependent and independent nursing activities and behaviors [21]. Dependent nursing activities require a doctor’s instructions and supervision and the doctor’s instructions are an essential element of the work. In Case 3, Case 5, Case 7, and Case 8, the nurse was convicted of involuntary manslaughter because of a failure to provide thorough follow-up observation of the patient’s condition and a failure to immediately report changes to the doctor. In addition, when a patient’s condition worsens into an emergency, nurses must do everything they can to solve the problem. For example, in the case of respiratory distress due to airway obstruction, airway maintenance should have been secured first by inserting an airway and/or repositioning the patient while notifying the doctor at the same time. This can be regarded as an independent nursing activity, and neglecting to carry this out was associated with a fatal outcome for the patient. A similar case of death due to insufficient follow-up observation of a patient admitted to the ICU was brought to the Supreme Court, which ruled that when a patient dies because of the failure of the night-shift nurse to take certain necessary measures, the hospital’s night-shift operation system ascribes the patient’s death to the nurse, but not to the on-call doctor (Supreme Court Decision of September 20, 2007; 2006Do294). Considering this court ruling, Shin [3] noted that the ruling is reasonable because of clinical reality. The similar incident in our study did not occur in the ICU, but in an emergency room and in the holding area waiting for admission, where the nurse-to-patient ratio is higher than in the ICU. In the ICU it is 1:2 or 1:3, but the emergency room does not have that care capacity for patients. In some countries, the ratio of emergency room nurses is also 1:2 [22], but in Korean hospitals the ratio of emergency room nurses at tertiary hospitals is 1:4 and 1:5 [22]. Although it is difficult to make comparisons due to a lack of in-depth research on emergency room nurse staffing levels, only 13.8% of all medical facilities comply with the standard of two nurses in charge of five inpatients as required under the Medical Service Act [22]. Since 86.2% of medical institutions are below grade 3 nurse staffing, the human resources standard for nurses under the Medical Service Act is very unfavorable [22]. In such a situation, the decision to ask nurses to take all the responsibility should be reconsidered because the follow-up observation of critically ill patients is nurses’ independent work.

Communication errors comprise the third type of error. Obtaining information from children through interviews is challenging and it is difficult to secure data. What pediatric patients communicate should be considered taking into account their developmental stage [10] and should be interpreted in the context of communication with their parents. Communication among medical team members is also important input for patient care. Ambiguous and delayed communication among medical team members can have harmful consequences for the patient.

The fourth area of nursing errors is the failure to delegate tasks efficiently. When caring for pediatric patients, the nurse most often delegates tasks to their caregivers. However, such delegation must also consider the “Five Rights:” right person, right task, right circumstances, right directions, and right supervision [15]. Although it was difficult to confirm the characteristics of this type of error among the reviewed cases, it should be emphasized that the role of the nurse is to provide clear instructions and to supervise according to the principles of these “Five Rights” when delegating.

Cases of noncompliance with the policies and procedures of the affiliated institution were mainly associated with neglecting the duty to educate and supervise. In Case 1, for example, the infection control policy was not followed. Lastly, the failure to use a device appropriately was identified in the case in which improper handling of a hot pack caused severe burns to a newborn (Case 4).

In this study, we analyzed court rulings regarding involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence by pediatric nurses. A particularly salient feature of this study is classifying the cases into the seven types of nursing error according to Austin’s nursing practice standards [15]. This legal expert in child health care has consistently established the seven safe nursing steps needed to protect nurses caring for children from legal problems by educating and implementing practical best practices for safe nursing [23].

It has been suggested that nursing associations in South Korea should also hire one or more lawyers to provide evidence and preventive education to minimize the legal problems of pediatric nurses. Cases of involuntary manslaughter or at-fault injury due to professional negligence by nurses caring for children were more frequently recognized as crimes than cases involving adults [10]. This might be explained by the nature of children, the professionals’ duty of care, poor follow-up observation, and the foreseeability of results, which weighed heavily in adjudicating the cases. In addition, death was the outcome in more than 50% of the incidents, and the injuries were mostly fatal injuries. In consideration of these points, pediatric nurses need to increase their awareness of the importance of observation, attention, and follow-up. Education programs are also required to improve the ability to assess children’s symptoms and signs. It is also necessary to recognize the importance of and provide education programs on the legal duties and responsibilities of nurses. Nurses will become more sensitive to the importance of patient care supervision if they recognize that the consequences of poor patient safety management can have fatal consequences for their patients. Nursing leaders and organizations such as the Korea Nursing Association should enact realistic nursing laws along with support for nurses so that nurses do not suffer damage from the blind spots in the law.

Although this study used only data from the legal documents of one country for data analysis, we tried to obtain as many precedents as possible by using as many sites as possible. However, due to institutional problems, some precedents could not be obtained. In addition, since data were classified according to the researchers' judgment for content analysis, there were possible limitations to the objectivity of the data.

CONCLUSION

Nursing errors in children were more often fatal and led to judgments of guilt in the courts than nursing errors in adults. To reduce these nursing errors, nurses need to commit to implementing relevant guidelines in their nursing practice and documenting their nursing activities in detail. In addition, legal awareness should be improved by educating nurses on their legal responsibilities. Nursing administrators should organize the regulations and guidelines related to each area of nursing work and respond sensitively to improve problems in each ward, including environmental and staffing concerns. We will continue to strive to establish a medical system that protects both patients and nurses by analyzing the precedents of cases in which pediatric nurses have been tried for negligence and by continuing education to increase the legal awareness of nurses.

Notes

Authors' contribution

Conceptualization: all authors; Data curation, Formal analysis: all authors; Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing: all authors; Final approval of published version: all authors.

Conflict of interest

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (No. 2021R1A2C1095530).

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

Acknowledgements

None.