First-time fathers' experiences during their transition to parenthood: A study of Korean fathers

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study was conducted to explore first-time fathers' experiences during their transition to parenthood in South Korea.

Methods

Data were collected from September 2019 to February 2020 through in-depth interviews that were conducted individually with 12 participants. First-time fathers with children under 2 months of age were recruited. Verbatim transcripts were analyzed using Colaizzi's phenomenological method.

Results

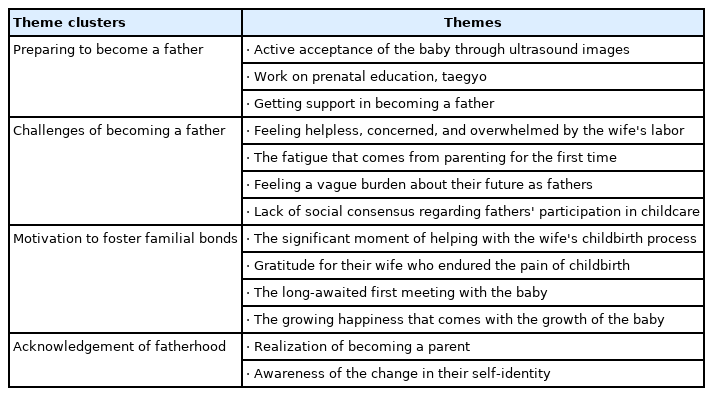

Four theme clusters were identified: Preparing to become a father, challenges of becoming a father, motivation to foster familial bonds, and acknowledgement of fatherhood.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that Korean first-time fathers prepared to practice parenthood through prenatal education, taegyo, and feeling bonds with their new baby. They recognized their identity as fathers and experienced self-growth. These results would be beneficial for health professionals in developing perinatal care programs, and the results provide basic data for studies on fathers and families during the transition to parenthood.

INTRODUCTION

While becoming a parent is generally a rewarding life experience, parents need to be well-prepared to welcome their new baby, and there are many challenges that follow. During the transition to parenthood, there are critical changes in the stages of life, and stress levels consequently increase, with a significant impact on the mental well-being of both the mother and the father [1,2]. A father's mental well-being and adaptation to the paternal role in the transitional period to parenthood are crucial not only for the father himself, but also for the family's health, including the wife's health and child's development [1,2].

In modern society, as the role of women in the workforce continues to grow and nuclear families become commonplace, the role of fathers in families is expanding, as they are no longer merely wage earners, but also co-parents and caregivers [3]. It is now easy to find fathers who attend prenatal care centers with their wives to take prenatal classes together, and the widespread family-centered childbirth culture has led to an increase in fathers' participation in childbirth. Fathers in the current generation tend to place their families at the center of their lives and value establishing a rapport with their children, taking part in parenting more actively [4]. According to the statistics from the Ministry of Employment and Labor in 2020, the use of childcare leave by South Korean (hereafter, Korean) men is steadily increasing, with numbers escalating from 1,790 in 2012 to 22,297 in 2019 [5]. The Ministry of Health and Welfare runs an official community named "A Hundred Fathers" to encourage new fathers to participate in childcare, and local governments are actively operating classes for fathers through Healthy Family Support Centers.

Concomitantly with recent changes in the role of fathers and the recognition of fathers' importance, research on fathers has been increasing. The expectant father begins to form a relationship with the coming baby by experiencing the wife's adjustment stages of pregnancy [6,7]. The extent of paternal-fetal attachment affects parenting stress and the relationship between the child and the father [6,7]. Research on first-time fathers' experiences has illustrated that fatherhood gradually develops from the process of adjusting to fatherhood, to developing the role of a father and then actively practicing fatherhood [8]. It has been reported that the active participation of fathers in parenting has a positive impact on children's social development [9], and beneficial interactions between fathers and children are closely related to a reduction in children's externalization of problematic behavior [10]. When fathers actively play with their children, it impacts child development more in terms of quality than quantity [11]. Additionally, active paternal participation in parenting contributes to an amicable marital relationship and reduces mothers' parenting stress levels [9]. The study of fathers' participation in parenting began to be addressed in earnest in Korea in the 1990s, with a significant expansion of research since 2011 [12]. Studies have mostly dealt with the effects of fathers' participation in parenting on children's social and emotional development, or on the quality of the marital relationship or mother's parenting stress, as well as quantitative analyses of the relevant variables that influence father's participation in childcare [9,11,12]. Although some studies have investigated paternal experiences among expectant fathers or fathers of infants, there is a gap in the literature in terms of qualitative studies that comprehensively cover experiences of paternal parenthood transition from early pregnancy to childbirth and parenting. The transitional period to parenthood is a new turning point for parents and an important starting point for the development of the child [13]. For healthy family dynamics during the transition to parenthood, qualitative research on both mothers and fathers should be actively conducted. In order to establish a theoretical framework for studying the paternal parenthood transition and seek ways to improve the health of fathers and families, efforts to understand fathers' own experiences during this stage should be prioritized.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Data, Korea's total fertility rate in 2019 stood at 0.92, the lowest birth rate among OECD countries [14]. While there may be various causes for the very low birth rate in Korea, it is difficult to disregard the changing trends of the younger generation who prioritize an independent lifestyle and choose to avoid getting married or having children for economic reasons [15]. Alternatively, it is also important to recognize circumstances in which married couples simply cannot have children due to issues of infertility. Within the current Korean status quo, extensive qualitative research exploring the parental experiences of first-time fathers, including the periods of pregnancy, childbirth, and childcare, are vital for gaining an exhaustive understanding of fathers' perspectives. Furthermore, this study will provide an opportunity to explore changes in societal perceptions and find ways to become childcare-friendly by understanding first-time fathers' experiences and perceptions of childbirth.

This study aimed to explore the transitional experiences to parenthood of first-time fathers and to provide basic data for the development of perinatal education and nursing interventions.

METHODS

Ethics statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cha University (No. 1044308-201907-HR-044-02). Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

1. Study Design

This qualitative study was intended to gain an in-depth understanding and descriptions of first-time fathers' experiences during their transition to parenthood, using phenomenological methodology. Phenomenological research allows a comprehensive understanding of the essence and semantic structure of an experience by revealing its existential meaning through the vivid experiences of research participants [16].

2. Participants

Among biological fathers whose first baby was born within 2 months, those who were willing to participate were selected as participants. The exclusion criteria consisted of those who had severe illnesses, those who had a wife or baby that was being treated for severe illnesses, and those who were either divorced or living separately due to serious marital problems.

The participants' demographic details are shown in Table 1. The participants had a collective average age of 33.5 years. Eleven of the participants had fathered one child, while one participant had fathered twins. Nine of the participants' wives had spontaneous deliveries, and three had undergone cesarean sections. Out of the 12 participants, 11 of their wives had given birth in hospitals, while one wife gave birth in a midwifery birthing center.

3. Ethical Considerations and Data Collection

The study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Cha University (IRB No. 1044308-201907-HR-044-02). The participants were recruited from hospitals or midwifery birthing centers in Gyeonggi Province, and the researcher explained the purpose and procedures of the study to the staff of each organization prior to obtaining permission to recruit participants. Doctors, nurses, or midwives then introduced participants who expressed interest in taking part in the study. Some participants' interviews were conducted in an outpatient clinic room provided by the hospital during their wives' postpartum checkups, while other participants' interviews were conducted at a cafe near their home. For ethical protection, the participants were given a detailed explanation about the purpose of the study, guaranteed anonymity and secrecy, asked for consent to record the interview, and informed of the storage and destruction method of the study data. The participants all provided written consent to voluntarily participate in the study. After completing the interview, each research participant was given a small gift.

Data were collected from September 2019 to February 2020 through in-depth interviews with the research participants. The interview questions were structured based on previous papers and related data. Each interview began with the main question: "Could you tell me about what you experienced during your transition to parenthood?" Subsequently, the researcher further proceeded with supplementary questions. The questions were asked in the order of the wife's pregnancy, delivery, and post-birth period, which was explained to the participants in advance. The supporting questions were as follows: "When did you feel most strongly that you had become a father during your wife's pregnancy, and could you elaborate on your thoughts and emotions at the time?", "How was your experience during your wife's pregnancy?", "How was your experience during your wife's childbirth?", "Could you tell me about the changes in your daily life after childbirth?", and "What has your parenting experience as a father been like?" The interview took approximately an hour and a half to two hours and was held once for each participant. During the interview, notable responses and characteristics of the participants were recorded in field notes. Data were collected until there was no more new information and the responses started to become redundant. Numbers were assigned to collected data, and transcripts were accessed with a two-step identification process with a password to ensure confidentiality.

4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was executed using the phenomenological method of Colaizzi [17]. First, the researcher listened to recorded interviews and the transcripts, including the field notes, which were then thoroughly reviewed to gain a general impression of the participant's experiences and make sense out of them. Second, meaningful statements were extracted from each participant's interviews, organized, and transferred to an Excel file. Third, a more general and abstract meaning was constructed from the extracted phrases without distorting the original meaning. Fourth, the significant aspects of the participants' described experiences were grouped together under a main theme. Fifth, similar themes were classified into theme clusters. Sixth, the transcript was examined once more to confirm that the research results accurately reflected the participants' experiences. Furthermore, the findings were presented to two participants themselves to confirm that the results reflected their experiences properly, and the fundamental structure of the findings was reviewed by a nursing professor whose feedback was reflected in the results. Seventh, the topics derived from the analysis were described and incorporated into clear statements by relating them with the phenomena of interest.

5. Ensuring Trustworthiness and the Researcher's Qualifications

This study was evaluated according to the criteria presented by Guba and Lincoln [18] to establish the validity and precision of the qualitative research results. First, to ensure credibility, participants who could clearly and fluently express their thoughts about the research phenomenon were selected, and semi-structural questions were asked to help participants describe their experiences precisely. The researcher actively listened to the participants' statements in a neutral manner. All interviews proceeded until there were no more new data, and what the participants said was exactly transcribed. The validity of the analysis was ensured by conducting a review process and examining the results with one nursing professor who has extensive experience in qualitative research. Second, in order to ensure fittingness, specific information such as the demographic characteristics of participants was defined, data collection procedures were presented, and rich descriptions of research phenomena were made. Third, in order to secure auditability, Colaizzi's analytic method [17] was followed, and the entire process of the study was delineated in detail. Fourth, in order to ensure confirmability, by keeping standards of reliability, fitness, and auditability, the researcher's bias was minimized as much as possible and neutrality was ensured.

The researcher conducted scale development research among expectant fathers by analyzing interviews through qualitative research methodology and has reviewed a number of qualitative research papers while participating in related seminars. The researcher has high research accessibility when it comes to conducting the study as she has numerous experiences of educating and nursing couples in the perinatal period while working as a nurse in the delivery room for several years.

RESULTS

Forty-eight meaningful statements, 13 themes, and four theme clusters that characterized first-time fathers' experiences during their transition to parenthood were extracted. The four overarching theme clusters were as follows: "preparing to become a father", "challenges of becoming a father", "motivation to foster familial bonds", and "acknowledgement of fatherhood". The results are presented in Table 2.

1. Preparing to Become a Father

1) Active acceptance of the baby through ultrasound images

Participants confirmed the baby's existence through ultrasound images and realized that they would become a father. The couple named the baby based on their desires and love. In a case where a couple had difficulties getting pregnant, the name was given to reflect the meaning of not having a miscarriage, with imagery evoking attachment to the mother's womb like sticky rice cake until she becomes fully pregnant. By giving their baby a name in the womb, fathers were able to actively accept the baby's existence.

My wife and I wanted to conceive a child naturally, but eventually went to a hospital. We had a hard time trying to conceive for a year. I always accompanied my wife to prenatal checkups. I strongly felt that I was becoming a father when I saw the baby in the ultrasound image. Because I could see something! The baby's birth name was Chaltteok (sticky rice cake). We named it that for the fetus to be attached to the mother's womb. (Participant 5)

I went to the hospital with my wife, and the doctor showed us the fetal ultrasound images. I saw a very small gestational sac and cried thinking that the baby was really there. The baby's birth name was Dalkong (something very small and cute like a bean). We named it soon after the prenatal checkup. (Participant 9)

2) Work on prenatal education, taegyo

Upon recognizing the baby's existence as real, participants made a commitment to take care of their health and live an upright life. Taegyo (traditional prenatal education) for the baby became a common interest for couples, and participants talked and read books to the baby. Participants also sang with their hands on the mothers' belly, calling out the birth name and sensing fetal movement, which the mothers very much appreciated. Participants tried predicting their babies' dispositions by observing fetal movement.

The doctor allowed us to hear the baby's heartbeat during the prenatal examination. 'Lub dub lub dub,' What a strong force! I promised to live a healthy and upright life as a father. I became careful about my words and actions. When the baby wiggled, I called out her birth name, putting my hands on my wife's belly. It felt like the baby was softly kicking the belly, so I wondered if she understood me. (Participant 8)

My wife solved math problems, sewed, and listened to music for the baby to be born. My wife talked to the baby often. I also called out my baby's birth name, read books, and sang often. The brisk fetal movement made me think that the baby would have a lively personality and enjoy exercising. I always put my hand on my wife's belly and stroked it. My wife loved when I did it and we used to laugh together. (Participant 10)

3) Getting support in becoming a father

Participants searched for information about the health of their wife and fetus through books and online sources. Prenatal education was helpful for participants to get ready to become a father. Participants made efforts to obtain knowledge about pregnancy and childbirth through prenatal education and were determined to guide their wife through this process as a father. Participants learned specific ways of becoming parents through taegyo activities such as talking to the baby and reading books to the baby, and prenatal education that dealt with topics such as prenatal care, helpful exercises and postures during pregnancy, postpartum breastfeeding, and postnatal care of the baby.

My midwife taught me taegyo activities such as talking to the baby, reading books to the baby, and postnatal care of the baby. Childbirth rehearsal helped the most. I learned the attitude I should have towards childbirth and watched the birth process through videos. It's amazing and impressive. I thought, 'This is how babies also suffer!' and made a firm determination to do well. (Participant 1)

I looked into books and online sources about pregnancy and childbirth. I took prenatal classes hosted by the nurses and doctors at the hospital my wife goes to. Prenatal education was helpful as it taught pregnant women's exercises, helpful postures during childbirth, and symptoms before childbirth. I also took taegyo classes. They taught us the importance of taegyo and how to do it. (Participant 8)

2. Challenges of Becoming a Father

1) Feeling helpless, concerned, and overwhelmed by the wife's labor

Most of the participants accessed information on childbirth, but it was difficult to distinguish the signs of upcoming childbirth in reality. The wife's labor time was longer than participants expected, and they felt sorry, helpless, and concerned that there was no way to help in an exhausting situation as the delivery progressed. They also stayed by their wife's side as they were worried that something bad might happen to their wife and baby during the delivery process.

My wife went through labor pains mostly at home. When we went to the delivery room, I was so shocked to hear that it was just the beginning of the process (sigh). I had learned about labor during my childbirth rehearsal, but as it was my first time, I was not able to tell if my wife was beginning the real labor process or not. As the labor process got more and more severe, I felt really helpless as there seemed to be nothing I could do for her (sigh). She was up all night and exhausted, so I was scared she might not have the strength to give birth, how the childbirth was progressing. (Participant 1)

There was no way to help her while she was in labor, and I was also stressed. I was sorry and uneasy, having mixed emotions. I remembered the things that I had done wrong to my wife, and I didn't know how time went by, but I just wanted the baby to come out as soon as possible. It took quite a while to take care of my wife after birth, but I wasn't hungry at all. Childbirth was over, and we returned to the hospital room, and only then did I realize that I was exhausted. (Participant 4)

2) The fatigue that comes from parenting for the first time

Although participants received prenatal education, they were relatively unprepared for how to care for their babies after birth. After the baby was born, they learned how to hold a baby, how to feed formula, and how to bathe a baby. They mostly learned to take care of their babies from their wives. They were unfamiliar with caring for babies, and it was difficult, so sometimes they had a hard time understanding why the baby looked uncomfortable. They felt a lot of physical fatigue while taking care of the baby; furthermore, it was difficult for them to have their own personal time and they were not able to rest.

I was so focused on pregnancy and childbirth that I neglected learning about childcare after birth. After the baby was born, I learned childcare skills from my wife such as holding, feeding, and bathing the baby. Now I can tell if the baby is hungry or hot when he cries, but sometimes the baby gets irritated, and we can't figure out why. When this happens, I really don't know what to do with the baby. (Participant 6)

My life changed completely after the baby was born. It's been about a month since my baby was born, and it's so hard. I can't rest after work. Now I have to take care of the baby when I come back from work. The baby doesn't sleep long so I don't have any personal time anymore. (Participant 9)

3) Feeling a vague burden about their future as fathers

Participants felt that their mindset changed as they became fathers. They felt a strong sense of responsibility and a financial burden that they had never experienced before. They recognized the importance of financial stability and thought about their ability to support their family and even more, their retirement age. They also tried to reduce household expenditures. They felt vague apprehension and burdens about the future.

I feel more responsible than when I lived with just my wife. My wife and I used to think about where to go and what to eat, but now I think twice before spending money. (Participant 7)

When I lived with my wife, I didn't think much about the future, such as working until retirement age, because my income was enough for both of us to live. However, I changed my mindset after having a child because I feel the burden of becoming a father. Thoughts of potential challenges and conflicts make me concerned. (Participant 10)

4) Lack of social consensus regarding fathers' participation in childcare

Participants knew that childcare leave policies are officially encouraged in Korea, but it was difficult for them to take childcare leave. Participants took paternity leave after their wife's childbirth but they did not dare use childcare leave due to financial burdens, job insecurity, and lack of awareness in the company. Participants felt a lack of social support regarding this issue, thought that the social awareness of fathers' participation in childcare was insufficient, and considered that a social consensus had not yet developed.

I got 10 days of paternity leave after my wife's childbirth. I also wanted to take childcare leave, but it's hard to do that because I'm walking on eggshells at my company. There's a lot of talk behind the scenes, and the company doesn't view taking childcare leave favorably. (Participant 4)

I used paternity leave after my wife's childbirth, but it's hard to take childcare leave. It's not easy to secure my place in the office. I could only take childcare leave if I were to risk losing my job (laughs). (Participant 10)

3. Motivation to Foster Familial Bonds

1) The significant moment of helping with the wife's childbirth process

While their wives went into labor, participants stayed by their sides. They held their wives' hands and helped them with their breathing and pushing. It was difficult watching their wives in pain, but they still helped with their childbirth. The participants felt proud as they helped their loved ones to endure pain while giving birth.

I wiped the sweat off my wife's face and helped her to the bathroom. I also gave her a massage. When my wife was pushing, I offered her hands even though there were handles on the bed. She held my hands so tight that after birth, my hand ended up swollen and bruised. My wife said that I was the only one she could rely on at the moment. I think I had been at least some help. (Participant 10)

The nurse helped my wife with how to push while giving birth. When my wife was pushing, I supported her upper body. The only thing I could think of was 'please come out quickly and healthy. Don't make it difficult for your mommy.' My wife said that at the end of labor all her strength was focused on the lower half of her body. So I realized it was coming to an end. They put a monitor on her belly so each contraction could be monitored. I kept track of the monitor, and when the contraction eased a bit, I told her to relax. When a contraction started again, I told her to push. (Participant 8)

2) Gratitude for their wife who endured the pain of childbirth

After their wives' long labor, participants were able to see the moment of childbirth. Participants experienced confusion and difficulties, but they became more grateful for their wives by watching the delivery process and were able to better relate to their wives.

I am grateful to my wife for putting so much effort into giving birth to our baby. My wife spent a prolonged, arduous time giving birth, but it was a precious time for us as a couple. I couldn't share my wife's labor pain, but I've come to understand childbirth by participating in it. I wouldn't have been able to empathize with my wife if I had missed it. (Participant 1)

After suffering with my wife in the delivery room, I was able to feel gratitude towards her and realized the preciousness of her. I thought I should help my wife well. Even if it only lasts a few days, I decided to change my attitude for her sake. (Participant 4)

3) The long-awaited first meeting with the baby

Participants were struck by the wonder of the birth of a new life and shed tears thinking about how much the baby must have suffered. Participants were able to cut the umbilical cord right after the baby was born and hug the baby themselves. Participants were able to sense the baby's warm body temperature through their first contact with the baby and feel their 9-month-long affection for the baby.

I cried the first time I saw the baby. It was touching to see the baby crying after struggling to come out. I wondered how hard it must have been for the baby to come out of that narrow opening. After the baby was born, I cut the umbilical cord and hugged the baby wrapped in cloth. Has it been about 10 seconds? The warmth of holding the baby was significantly different from looking at the baby's face. I had a special feeling about the baby. (Participant 8)

I first held the baby after cutting the umbilical cord. I was trembling and felt overflowed with emotions. Tears were in my eyes. I think it was because I recalled my wife enduring the process and I was excited to see my baby. She was not at all unfamiliar. (Participant 5)

4) The growing happiness that comes with the growth of the baby

As participants took care of the baby, the baby's appearance and behavior became a new source of happiness in their daily lives. It was amazing to see the baby growing up every day, and they observed the baby's smile and facial expressions and made eye contact. Participants thought that the presence of the baby gave them joy in their daily lives. While taking care of the baby, fathers became more intimate with their wives and helped each other.

I feel good taking care of my daughter, and she is gorgeous. She eats and pees really often, so it's wondrous how much more she will grow. When I'm with my baby girl, I observe her expressions and it's great joy to see her smile. It's a new happiness in my life. She makes eye contact with me and turns her head when I call. I love these moments because my baby recognizes me. (Participant 12)

It's hard to take care of a baby, but I smile with my wife while looking at the baby and this is our pleasure. It's also fascinating. There are feelings we wouldn't have known without our child. My wife and I didn't think about having a baby after marriage, but we made a decision to try, and now I'm really glad about that decision of having a baby. (Participant 8)

4. Acknowledgement of Fatherhood

1) Realization of becoming a parent

Through childbirth, participants had the opportunity to look back on how their parents must have felt and the difficulties they must have faced during the participants' childhood. They came to feel grateful about their parents and the importance of their roles in continuing the next generation.

After the baby was born, I called my mother first. She liked it a lot. My father passed away in middle school, so I don't have many memories of him, but while taking care of my babies, I think of my parents and realize that it must have been hard for them to raise me. (Participant 7)

I called my father as soon as the baby was born, and I felt emotional. When I told him the news, I said "thank you!" without realizing it. I came to care more about my parents after the birth of my child. (Participant 5)

2) Awareness of the change in their self-identity

During the transition to parenthood, participants became aware of their identity as fathers. They appreciated their babies and realized the meaning of family with their children. As new fathers, participants initially had a hard time parenting. However, as they continued to engage in childcare, they were able to realize that they were becoming a father, and this enabled them to gain confidence in parenting. They wanted to share good experiences with a new member of the family. As the participants recalled their own fathers, they reflected on their roles to their newborn babies and desired to become friendly, exemplary fathers. As fathers, they had opportunities for self-growth.

My wife and I often thank the baby for coming into our life. Raising a child is a great happiness. Our child is more precious because we had trouble getting pregnant. As I raise my child, I feel like I have grown up and I really like the feeling of being together. My father was very considerate of me. We held a lot of conversations, and he wasn't particularly strict towards me either. I don't want to raise my child in a fixed mold. Instead, I want to be able to properly guide him along whatever path he plans to take. My hope is that I will be able to help my child take on endeavors of his own choosing rather than feel pressured to meet my own expectations. I want to be a role model for my child. (Participant 11)

I didn't know anything about childcare but as I do this little by little, I feel like I am becoming a father. When I'm taking care of my baby, I always try to think positively and that I can do it. Even though I am not doing good, I think I'm getting better as I tell myself that I am doing a good job with childcare. I think being a parent is the process of becoming an adult. Marriage does not change who we are. It is the perspective toward the world and myself that changes after the birth of a child. My father is a very brusque person and doesn't express his emotions outwardly, but I want to talk a lot with my child and be a friendly father. (Participant 4)

DISCUSSION

This study applied phenomenological methodology to deeply understand the experiences of first-time fathers' parenthood transition in the sociocultural context of Korea.

The first theme cluster, "preparing to become a father," contains experiences related to participants' mindset and behavior, which changed due to the presence of a baby. According to a previous study, expectant fathers were able to acknowledge the baby's presence by attending prenatal ultrasound appointments, speculating about the baby's personality, and naming the baby [19], similar to the results of this study. Providing expectant fathers an opportunity to recognize the fetus through ultrasound images is very important as it becomes the basis for attachment to the child [6,7]. Expectant fathers performed practical activities such as letting the fetus hear their voices, touching their wife's belly, and sensing fetal movement as the pregnancy progressed [19]. Participants in this study tended to value not only interactions with the baby, but also their mindset towards the baby in their daily lives. They made a commitment to live an upright life and prudently chose their words and actions. They also actively practiced interacting with the baby to be born, such as talking to their baby, singing and reading books for the baby. Taegyo was a common interest for couples, and they worked hard on it together. This illustrates that the Korean tradition of taegyo is naturally inherited by modern couples. Taegyo refers to prenatal education and care for the fetus, and in Korea, paternal taegyo as well as maternal taegyo is emphasized to couples during pregnancy [20]. This tradition developed from a general framework providing guidance on living and proper mindsets to a specific prenatal education method [20]. Utilizing various forms of prenatal education, taegyo programs are highly beneficial for developing parental-fetal attachment in first-time parents [21]. These programs are significant as they encourage fathers' active participation in their wives' childbirth and childcare. Tailored taegyo-focused prenatal programs in Korea that encourage fetal attachment among expectant parents should be promoted. Moreover, most participants joined prenatal education programs operated by their local hospital intended for first-time parents. However, to stimulate novice fathers to engage in childcare to a greater extent, more initiatives should be taken on a national level (e.g., through public health centers) to facilitate these social support systems.

The second theme cluster in this study, "challenges of becoming a father," includes the difficulties of participating in childbirth and childcare as a father. Participants were flustered by the birth process as it was different from what they had expected, and they experienced negative emotions such as helplessness, anxiety, and fear. This is similar to a previous study [22]. Since spousal participation in childbirth has become common, it is necessary to promote childbirth preparation nursing intervention programs that also include the husbands of pregnant women. Through prenatal education, expectant fathers should prepare psychologically and gain the necessary skills to support their wives' childbirth. This will allow both parents to experience a desirable childbirth process, which will consequently lay the foundations for a secure father-child relationship. The interviews in this study were conducted within 2 months after childbirth during the postpartum period, when participants' wives faced severe sleep deprivation and fatigue due to night feeding and childcare. It was very difficult for fathers to take part in childcare during this period. First-time fathers had many difficulties in taking care of babies due to their lack of preparation for childcare skills [23]. Since the focus of most prenatal education is mainly on mothers and babies, there are insufficient opportunities for expectant fathers to learn childcare skills [23]. Although the participants of this study also took prenatal classes, they were only able to learn specific practical childcare skills from their wives after childbirth. In order to encourage expectant fathers to actively engage in parenting education and acquire the appropriate childcare skills from the prenatal stage, it is necessary to develop and administer education programs planned by health professionals specifically for fathers. Fathers in the new generation can easily access information online through advances in information technology, so it is important to develop smartphone apps or online nursing intervention programs and apply them in real life. Through the Seoul Maternal Early Childhood Sustained Home-Visiting Program, the Seoul metropolitan government has been providing mothers with opportunities to learn about parenting skills after childbirth [24]. These programs should not be limited only to mothers; instead, health professionals should also include fathers in childcare education. Participants knew that childcare leave policies are officially encouraged in Korea, but it was difficult for them to take childcare leave in reality. Article 18-2 of the current Act on Equal Employment Opportunity and WorkFamily Balance Assistance guarantees 10 days of paid paternity leave when a spouse gives birth, Article 19 of the same Act stipulates that men can apply for childcare leave, and Article 20 provides institutionalized support from the state for workers' childcare leave benefits [25]. Men's use of 10-day paternity leave after his spouse's childbirth is common, but in reality, the current childcare leave system still has problems because it has a low rate of use by male workers due to reductions in household income, continued instability in working relations, and a lack of widespread awareness about male childcare leave. It has also been suggested that a "father quota" system, which allocates a period of childcare leave to fathers in Nordic countries, should be introduced, and the income replacement rate of childcare leave benefits should increase [26]. Studies have also shown that the participation rate in childcare was higher among fathers who worked in family-supportive workplaces with flexible work [27]. Given the reality of Korea's low birth rate, realistic social support and improved awareness among employers, supervisors, and coworkers will be necessary for childcare-friendly measures.

The third theme cluster in this study, "motivation to foster familial bonds," encompasses the emotions felt by fathers as they faced changes in family relationships after the baby's birth. Participants felt bonds with the baby through cuddling and cutting the umbilical cord immediately after birth. They also had time for skin-to-skin contact with the baby, and they described this experience positively, which is similar to a previous study [28]. The emotions that the participants felt during the initial parenting process after welcoming their new family member became the basis for forming familial bonds. As they watched the delivery process, participants felt deep gratitude for their wives who gave birth. They recognized the importance of fathers' supportive role in childbirth and evaluated their caring behaviors positively, as in a previous study [28]. Husbands' participation has become common in spontaneous deliveries, but it is still difficult in cesarean deliveries. Even in this study, if the wife had a cesarean delivery, the paternal experience gained during childbirth was inevitably limited. Paternal participation in cesarean deliveries should become more prevalent except in cases of emergency surgery. Participants found it challenging to take care of the baby, but they and their wives were able to help each other and share happiness. According to a previous study, skin contact between the baby and the father during childcare helped to reduce stress and promote interactions between the baby and father [29]. Furthermore, fathers' active participation in childcare is not only beneficial for the couple's amicable marital relationship, but also provides a basis for adapting to the paternal role [30]. Thus, encouraging fathers to participate in parenting should be encouraged.

The fourth theme cluster of the study, "acknowledgement of fatherhood," includes changes in the participants' mindset, lifestyle, and self-identity that occurred in the process of becoming a father. Influenced by the birth of their child, participants ruminated on the importance of family and their own parents. Furthermore, as they took care of the babies, they had the opportunity to reflect upon their parents' difficulties and feel gratitude towards them. In this process, they were able to become aware of their identity as fathers and experience self-growth [13,30]. Whereas the previous generation of fathers stressed authority and discipline over their children, fathers in the current generation report a desire for a more progressive position in their children's lives, one that is more approachable and affectionate than that of the past [4]. Since fathers' experiences during their transition to parenthood have a lasting impact on the formation of father-child relationships and the health of the family, prenatal education programs in clinical settings and childcare education and support systems operated by health professionals targeting fathers in the postpartum stage should be implemented and promoted. In addition, to increase fathers' participation in childrearing, it is necessary to improve the quality and convenience of education programs by deploying social support systems through local governments, social welfare centers, and public health centers.

Qualitative studies of the paternal parenthood transition can provide evidence-based data for appropriate information and support for health managers and nurses responsible for perinatal health care. This study presents the need to develop and implement a nursing intervention program for fathers before and after childbirth, which could be used as a foundation for father and family research. Moreover, unlike the factors that have contributed to Korea's low fertility rate, the participants' experiences and determination to become full-fledged parents will be the impetus for the rediscovery of the meaning of parenting and the emergence of social interest in the value of childbirth and parenting.

This study has certain limitations. First, an attempt was made to include more cases where participants' wives gave birth in birthing centers such as midwifery birthing centers in addition to hospitals, but there were difficulties in recruiting participants. Future studies should be conducted among fathers who have experienced childbirth in various delivery places. Additionally, most participants in the study were people who actively practiced attachment to the fetus from the start of pregnancy and proactively participated in childcare; therefore, the generalizability of these results to all fathers is limited. Factors affecting fathers' participation in parenting include their level of education, whether the child is a twin, the presence of someone to help with parenting, and dual-income status [11]; however, the children of the participants had been born within 2 months of this study, which is a relatively short period, meaning that there is a limit in the degree to which those factors were revealed. The majority of the wives of participants gave birth in hospitals, and a gynecologic postnatal checkup after childbirth is usually conducted at 1 to 2 months postpartum. Many of the interviews were conducted at the time of these checkups. This inevitably meant that a single interview encompassed questions on all the stages from pregnancy to childbirth. In future studies, more data will be obtained if additional interviews are conducted online or through phone calls. Furthermore, participants' opinions on perinatal education and complaints regarding the medical environment during the delivery process were not sufficiently addressed in this study, so future studies will need to investigate fathers' satisfaction and requests for nursing intervention during their wife's pregnancy, childbirth, and postnatal care.

CONCLUSION

This study was conducted to gain an in-depth understanding of first-time fathers' transitional experiences to parenthood in Korea. Data were collected in in-depth interviews and were analyzed using the phenomenological method. The following theme clusters were identified: "preparing to become a father", "challenges of becoming a father", "motivation to foster familial bonds", and "acknowledgement of fatherhood". First-time fathers developed a healthy mindset after their wife's pregnancy. They started forming attachments through taegyo activities for the baby. Participation in childbirth was stressful, but participants became more grateful for their wives' hard work and experienced special moments with their new babies. As novice fathers, they found it challenging to take care of their babies, but they experienced the joy of everyday life and intimacy with their wives. Furthermore, they became aware of their identity as fathers and experienced self-growth. By reflecting on participants' needs and the sociocultural context of Korea, it can be concluded that psychological parenting programs and systematic prenatal education for first-time fathers should be actively conducted.

Notes

Authors' contribution

Conceptualization: Nan Iee Noh; Data collection, Formal analysis: Nan Iee Noh; Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing: Nan Iee Noh; Final approval of published version: Nan Iee Noh

Conflict of interest

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

Acknowledgements

None.