Development of a violence prevention educational program for elementary school children using empathy (VPEP-E)

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study describes the development of a violence prevention educational program for elementary school children using empathy (VPEP-E) that teachers can use during class.

Methods

Hoffman’s theory of empathy and Seels and Richey’s (1994) ADDIE model were applied to develop this program.

Results

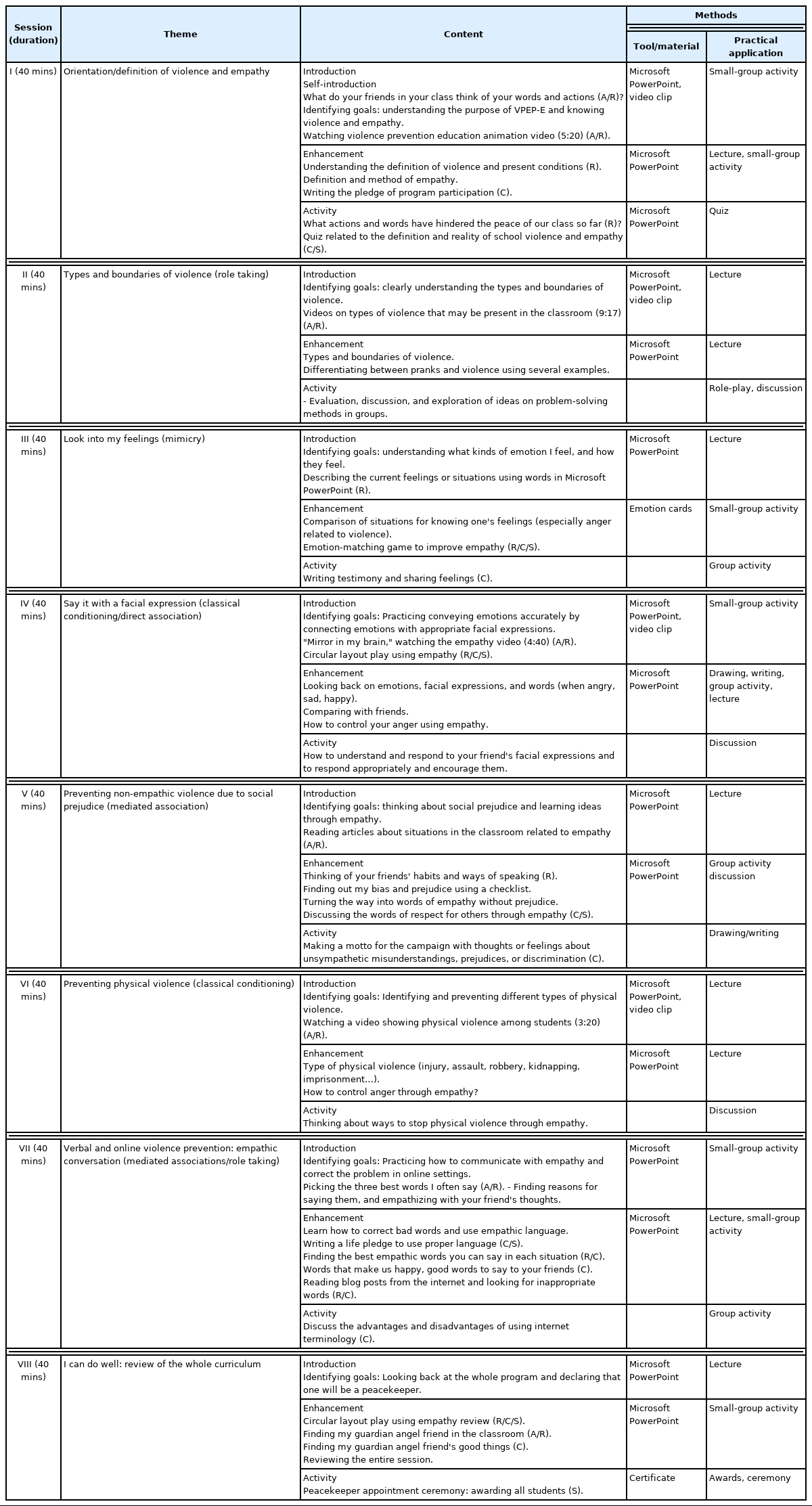

The developed program consisted of eight sessions: Orientation/definition of violence and empathy, types and boundaries of violence, look into my feelings, say it with a facial expression, preventing non-empathic violence due to social prejudice, preventing physical violence, verbal and online violence prevention: empathic conversation, and I can do well: review of the whole curriculum. The program was evaluated by 15 elementary school teachers, who considered it to be easily accessible to elementary school students. The final VPEP-E, which will be provided in eight times for 40 minutes each for fifth-grade students, will provide a basis for preventing violence by fostering empathy.

Conclusion

We expect the developed educational program to be effective in preventing violence among elementary school students. However, further research involving children from various age groups is needed.

INTRODUCTION

1. Need for Study

Violence refers to the use of force, such as fists, feet, or sticks and other weapons, to subdue others through the exercise of power that causes injury or destruction [1]. There are many kinds of violence, including physical, verbal, sexual, and emotional. Although there is no inherent limitation on where violence can take place, it commonly occurs at home, school, work, street, or cyberspace [2].

As violence manifests through examples of cruel collective behavior, effective strategies are needed to prevent further incidents of violence [3,4]. Violence among school children is a serious and persistent social problem in South Korea, where it occurs at an early age and with problematic severity [3]. The 2019 school violence survey conducted by the Korean Ministry of Education revealed that students in elementary schools (aged 9 to 11 years) experienced more violence than those in middle and high schools [5]. Furthermore, the ways in which students are victimized by violent behavior are complex. The survey showed that 41.4% of the students who experienced group bullying also experienced verbal abuse, and 27.0% of those who experienced verbal abuse also experienced group bullying [5].

Although school years are critical for children’s development, many children are exposed to violence during this period in their lives [6–8]. According to a 2019 report on school violence, most violence starts in elementary school [7], and violence most commonly occurs in the form of verbal abuse and harassment or bullying by classmates through text messages and social media [6,7]. As more young children have an access to mobile phones and computers, they can also access information on crime and violence more easily on the internet and social media; there has been an increase in their attempts at imitating such behavior [3]. Group bullying is becoming more common as students can easily communicate with each other through online messaging applications, and their actions are becoming more vicious as they share pictures and videos on social media, knowing how information spreads like wildfire on the internet [3,6]. Experiencing these forms of victimization, such as verbal abuse, group bullying, and cyberbullying, negatively impacts children’s growth and interferes with their healthy social development [6,9].

School violence is not a one-time incident; instead, it is a pattern of consistent and systematic behavior [6]. In elementary schools, it occurs among emotionally insecure school children who are strongly dependent on their peers [6]. This behavior therefore takes on a strongly collective character and sometimes causes bullying to evolve into cruel and criminal behavior [10,11]. Although bullying negatively impacts the victim’s academic performance and physical, mental, and emotional health, perpetrators often do not feel guilty [8,10, 11]. According to Olweus [12], the most common characteristic of perpetrators is that they empathize little with others and are inconsiderate. They feel an urge to dominate others [12]. They show no sympathy and ignore the rights and emotions of others. However, the experiences of the victims of violence and the perpetrators of violence tend to be cyclical, and anyone can become a victim or a perpetrator [10]. Since students who are severely victimized may become perpetrators in the future, when dealing with violence, one must first approach the situation by tackling students’ attitudes and thoughts regarding violence and their empathic abilities, rather than approaching the victim and the perpetrator separately [13].

Currently, elementary schools in South Korea operate a school violence prevention education program as part of character-building education to solve these problems [5]. Previous studies have shown that violence prevention education in elementary schools not only reduces various types of violence and acts of violence, but also prevents future violence [11,14]. However, there is a limit to the persistency and effectiveness of this program because it is operated autonomously, with variation depending on the school and the teacher conducting it [11]. Therefore, a systematic and ongoing effort to prevent school violence is needed to help students become defenders instead of panicking when they encounter violence and to encourage perpetrators to empathize with victims and feel remorse for their behavior.

Empathy can be understood as a vicarious experience of the feelings or thoughts of another person and an affective response more appropriate to someone else’s situation than one’s own [15]. In addition to its importance in counseling and treatment, it is also a key element of interpersonal relationships [10]. According to a study by Im and Oh [11] targeting elementary school children, improvement in one’s ability to empathize helps one to understand one’s own and others’ desires and to become more considerate. Since empathy is an essential virtue for the well-being of society, education must aim at improving empathy in every student to prevent violence [12,13]. When a person lacks empathy, they may ignore someone who is in trouble and worsen relationships by responding aggressively to conflicts [10].

According to previous studies, depending on a person’s capacity to empathize, one may become a bystander or a defender of a victim [15]. Koc’s study [16] reported that there was a significant negative correlation between tendency to violence and empathic ability. Therefore, violence can be reduced by improving empathy among all elementary school students, including the victims, perpetrators, and bystanders [10,11]. Additionally, enhancing a child’s ability to sense and understand other people’s feelings will positively affect his or her psychological and emotional development, creating a foundation for social interactions and moral development. Since empathy has beneficial results in terms of reducing violence [11,13,17,18], fostering empathy is of vital importance in preventing and solving various types of violence.

However, studies on violence in South Korea have mostly focused on adolescents [4,10,13,17], elementary school student bystanders [11], teachers [18], and parents [19]. Thus, there is a lack of research on violence prevention education programs that aim to improve empathy in school children. To address this gap, it is necessary to develop a violence prevention education program that uses empathy to prevent violence effectively. A program of this type may provide practical guidelines to improve children’s psychosocial health by preventing and reducing violence among elementary school children.

2. Purpose

This study developed a violence prevention educational program using empathy (VPEP-E) for elementary school children that provides basic guidelines on preventing violence and can be used by teachers and health teachers can utilize it in fieldwork.

3. Theoretical Framework

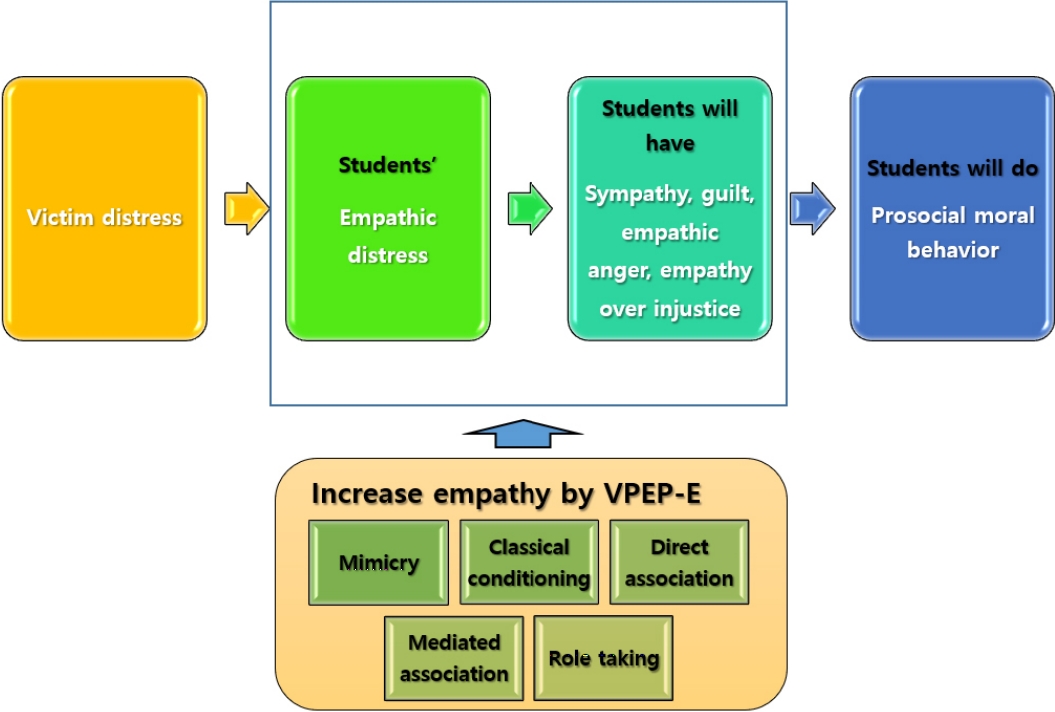

Hoffman’s Empathy Theory [15] was employed as the theoretical framework of this study. Empathy is a resource that causes prosocial moral behavior through sympathy, guilt, empathic anger, and empathy over injustice [15]. Hoffman’s theory describes five arousal patterns of empathy: mimicry, classical conditioning, direct association, mediated association, and role taking [15].

Mimicry refers to the process of imitating the emotional expressions of the victim’s face, voice, and posture, through afferent feedback with emotions consistent with those of the victim. Classical conditioning describes how a child forms the basis of an empathic response by generalizing conditioned stimuli through expressions and behaviors in encounters with others and the resulting feelings. Direct association refers to feeling the emotions appropriate to the victim’s situation based on reminders of one’s past experiences through clues, such as facial expressions, behavior, and language, seen in the victim’s situation. Mediated association involves a reminder of one’s past experiences by looking at clues arising from the verbal mediation of information about the victim. Role taking is a way of empathizing by “thinking about someone else’s position” and considering “what other people are feeling”.

Based on this, the VPEP-E included five empathy-arousing components. Elementary school students who develop empathy after participating in the VPEP-E are expected to experience empathic distress related to the victim’s distress and to engage in pro-social moral behavior after experiencing sympathy, guilt, empathic anger, and empathy over injustice (Figure 1).

METHODS

1. Study Design

This methodological study provided basic data for implementation in the field by developing a program for preventing violence among elementary school children using empathy.

2. Study Procedure

1) Instructional systems design and educational strategy

The goal of this study was to develop an educational program using empathy to prevent violence, ultimately promoting the health of elementary school children. Accordingly, the phases of analysis, design, and development in the ADDIE (analysis, design, development, implementation, evaluation) model proposed by Seels and Richey [20] were applied as the framework for developing an instructional system (Figure 2). The ADDIE model was suitable for this study as it helps to develop a program by setting goals, analyzing the existing literature, and analyzing the educational needs of students and teachers. Then, developers reflect on these issues based on evaluation and feedback from a group of field experts, ensuring that each step is mutually recognized and elaborated. As a widely-used teaching design model, the ADDIE model is regarded as a system that promotes organic interactions among learners, teachers, class materials, and learning environments to facilitate learning.

The process of this study according to ADDIE. VPE, violence prevention education; VPEP-E, violence prevention education program using empathy.

The teaching strategies of the ARCS theory [21]-attention (A), relevance (R), confidence (C), and satisfaction (S)-were used as educational strategies in this program. During the design phase, the aim was to imbue the introduction of every session with motivation (A), and the content was related to actual experiences to induce interest and increase the effectiveness of education (R). At the stage of group activities after learning, students were provided with activities that could be easily carried out and checked to make them feel confident and satisfied about doing well (C and S). Of particular note, the ADDIE model requires an appropriate strategy for the design phase [20]; for this reason, the ARCS theory was utilized in this study.

3. Procedures and Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board (HIRB-2020-EX004) of Hallym University after submitting a research proposal for the purpose, contents, and methods of the study. It was evaluated as having no ethical issues during the entire study process. The program development was conducted from July to August 2020 according to the procedure presented in the study results.

1) Analysis phase

To analyze educational needs, learners, and the environment, we conducted preliminary research among 195 elementary school students in fifth and sixth grades to identify content related to violence prevention in the upper grades of elementary school [22]. First, 74.9% of the participants stated that violence prevention education was necessary, indicating that upper-grade elementary school students wanted to receive education on this topic. Students’ level of empathy and awareness of violence were higher than the median values, and their attitude toward violence was lower than the median values for permissive and bystander attitudes. Empathy had a significant negative correlation with both permissive and bystander attitudes toward violence. According to the results of a previous study [22], it was thought that increasing children’s level of empathy could prevent violence by promoting the understanding the victim’s position in a violent situation and discouraging children from standing by while violence is carried out. Therefore, it seemed necessary to emphasize education on empathy in violence prevention education for children in the upper grades of elementary school.

A literature review related to empathy and violence prevention education programs was conducted. We searched for studies published from the earliest available date until August 2020 that described the application of programs related to “violence” and “empathy” for children. We shared the references identified in the literature review with the panel 1 week before meeting for the first discussion. Four in-depth discussions, lasting for over 2 hours, were conducted with an expert panel that included two elementary school teachers, one health teacher, and three professors in the nursing department. In the first discussion, all the panel members reviewed the literature. Then, in the second discussion, the current status of the study was reviewed. In the third discussion, key words relating to violence prevention education for elementary school students were extracted, and in the fourth discussion, these terms were organized into content categories to help fifth-graders understand the relevant concepts by using empathy, and all of the panel members reached a consensus. Based on the literature review and expert opinions, the content categories of the VPEP-E were summarized as “definition of violence and empathy”, “types and boundaries of violence”, “role taking for empathy”, “mimicry with imitation and feedback”, “conditioning and association in facial expression”, “non-empathic violence due to social prejudice”, “classical conditioning and physical violence”, and “empathic conversation as preventing verbal/online violence”.

2) Design phase

The program was designed to achieve its goals in a way that would make it easy for the students to understand and implement empathy in real life. It had eight sessions, as follows: “Orientation/definition of violence and empathy”, “Types and boundaries of violence” (role taking),”Look into my feelings” (mimicry), “Say it with a facial expression”(classical conditioning/direct association), “preventing non-empathic violence due to social prejudice”(mediated association), “Preventing physical violence”(classical conditioning), “Verbal and online violence prevention: empathic conversation (mediated associations/role taking)”, and “I can do well: review of the whole curriculum”. Each session started with an introduction, followed by an elaboration of the learning points (referred to hereafter as “enhancement”), and ended with an activity. Hoffman’s arousal patterns [15] were used in each session to increase empathy, which induces prosocial behavior, by encouraging participants to feel empathic distress towards the victim’s distress.

We also applied attention (A), relevance (R), confidence (C), and satisfaction (S) from the ARCS theory [21] to the content of the educational strategies. The reason for applying Keller’s ARCS theory [21] was to maximize the effect of violence prevention education by increasing empathy. Therefore, the instructional strategy involved stimulating motivation. The material was designed to be interesting to draw attention (A), and the content was related to participants’ own experiences of violence (R). Problems that students could easily solve were provided to foster their confidence in practicing the relevant skills and to facilitate post-learning evaluation (C). Through these measures, students could feel the satisfaction of being able to carry out these skills (S). This program focused on maximizing the effects of violence prevention educational program.

3) Development phase

The main content of the lectures was summarized using Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). The Microsoft PowerPoint slides were created using clear colors, fonts, and font sizes that elementary school students could easily understand and focus on. The text contained simple and easy words in keeping with the sentence-reading ability of elementary school students.

After the development of this program, a group of experts were requested to verify the validity of the content and to further improve the program. As a tool for evaluation, a feasibility questionnaire for experts was constructed by supplementing the instrument for evaluating satisfaction with training programs [23]. The evaluation scale consisted of a total of nine items, including appropriateness, usefulness, helpfulness, effects, satisfaction, intention to recommend the program, willingness to participate as an instructor, willingness to incorporate the program into one’s practice in the field, and suggestions. To verify whether the scale was appropriate to use for this study, the content validity index (CVI) for these nine items was reviewed by experts, including four elementary school teachers, two health teachers, and three nursing department professors using a 4-point Likert scale (1=not relevant, 2=somewhat relevant, 3=quite relevant, 4=highly relevant). The evaluation scale was verified as valid, with item CVIs ranging from .89 to 1.00 and a scale-CVI of .99, which indicated that it was a suitable measurement for evaluating the developed program [24].

4) Formative evaluation

The evaluation process in ADDIE is conducted in two stages: formative in the development phase and summative in the evaluation phase [20]. The program evaluation of this study was a formative evaluation, which includes obtaining appropriate information and using this information as a groundwork for further development [20].

The program was evaluated by 15 elementary school teachers after developing and verifying it. We created a program book that included the content of all eight sessions of the program and sent it to them by mail. After reviewing the content of the program book, they filled out the enclosed paper-based questionnaire and wrote down comments on directions for further improvement. To reflect their suggestions, the order of role play was adjusted to two sessions, and the terms were changed to reflect the groups used by elementary school students. Ultimately, the total satisfaction level of the 15 elementary school teachers was high, at 3.64±0.29 for the eight items (Table 1).

RESULTS

This program was developed by applying Hoffman’s Empathy Theory [15] and the ARCS theory [21] through the ADDIE model [20]. The final content of the program, as supplemented by the implementation and evaluation of 15 teachers, is described below (Table 2).

In the first session, “Orientation/definition of violence and empathy”, the goal is to understand the purpose of VPEP-E and acquire knowledge of violence and empathy. In the introduction, students are given time to think about their friends in the class, their words and actions, and watch the related videos (for attention and relevance). In the enhancement portion of the session, a lecture is then prepared to improve participants’ understanding of empathy and violence-related knowledge. For the activity, students write the pledge of participation (for confidence). Finally, students think about what actions and words hinder the peace of the class (for relevance) and take a quiz (for confidence and satisfaction).

In second session, “Types and boundaries of violence” (role taking), the goal is to clearly understand the types and boundaries of violence. In the introduction, students watch videos related to violence that may have occurred in the classroom (for attention and relevance). Then, for enhancement, students learn about the types and boundaries of violence and differentiate between pranks and violence through several examples. As an activity, students perform role-plays using actual examples of violence based on what they see in the video (for attention, relevance, and confidence). Finally, they evaluate and discuss ideas on problem-solving methods in groups.

In third session, “Look into my feelings” (mimicry), the goal is to understand the types of emotions that are felt and how they feel. The introduction involves describing current feelings or situations that they are facing (for relevance). Next, for enhancement, they compare situations where one knows one’s feelings (especially anger related to violence) and play an emotion-matching game to improve empathy (for relevance, confidence, and satisfaction). The group activity, writing exercise, and sharing feelings relate to confidence.

In the fourth session, “Say it with a facial expression” (classical conditioning/direct association), the goal is to practice conveying emotions accurately by connecting emotions with appropriate facial expressions. In the introduction, students watch an empathy-related video from the Korean Educational Broadcasting System (EBS) (“Mirror in my brain” [4:40], for attention and relevance) and engage in circular layout play using empathy (relevance, confidence, and satisfaction). Next, for enhancement, students practice looking back at emotions, facial expressions, and words (when angry, sad, and happy) and compare their experiences with those of their friends as a small-group activity involving drawing and writing, and a lecture is given on how to control one’s anger through empathy. For the activity, a discussion about how to understand and respond to a friend’s facial expressions and how to respond appropriately in an encouraging manner is planned.

In the fifth session, “Preventing non-empathic violence due to social prejudice” (mediated association), the goal is to think about social prejudice and learn ideas through empathy. In the introduction, a text about situations in the classroom related to empathy (for attention and relevance) is read. Next, for enhancement, a lecture addresses the topics of thinking about a friend’s habits and ways of speaking (for relevance), identifying one’s biases and prejudices using a checklist, and using words to express empathy without prejudice, followed by a group activity. Subsequently, respectful words for others through empathy (for confidence and satisfaction) are discussed. As the activity, students create a motto for a campaign designed to address thoughts or feelings about unsympathetic misunderstandings, prejudices, or discrimination (for confidence).

In the sixth session, “Preventing physical violence” (classical conditioning), the goal is to identify and prevent different types of physical violence. For the introduction, a video dealing with physical violence among students is provided (for attention and relevance). Then, for enhancement, a lecture on types of physical violence and how to control anger through empathy is delivered using Microsoft PowerPoint. The activity involves a discussion on ways to stop physical violence among students through empathy.

In the seventh session, “Verbal and online violence prevention: empathic conversation”(mediated associations/role taking), the goal is to practice communicating with empathy and to rectify problems in online settings. The introduction involves a small-group activity where students pick the three best words that they often use (attention and relevance), find reasons to use them, and practice empathizing with a friend’s thoughts. Next, for enhancement, a lecture and small-group activity deal with how to correct hurtful words and use empathic language, writing a life pledge to use proper language (confidence and satisfaction), finding the most empathic words that one can say in each situation (for relevance and confidence), words that make one happy, and good words to say to friends (for confidence). Finally, blog posts from the internet are read and inappropriate words are identified to strengthen previous activities (relevance and confidence). The group activity includes a discussion about the advantages and disadvantages of using internet terminology (confidence).

In the eighth session, “I can do well: review of the whole curriculum”, the final goal is to look back at the entire program and declare one’s intention to be a peacekeeper. After repeating the circular layout play using empathy (for relevance, confidence, and satisfaction), students find a guardian angel friend in the classroom (attention and relevance) and identify the guardian angel friend’s good qualities (confidence). The instructor reviews all sessions again with a Microsoft PowerPoint lecture. The final activity is the Peacekeeper Appointment Ceremony, where all students receive an award (satisfaction).

Regarding the formative evaluation, the developed VPEP-E was considered appropriate to educate fifth-grade elementary school children by 15 school teachers. The final VPEP-E will be provided in eight times of 40-minute sessions to a class of fifth-grade elementary school students in the classroom by the authors. Thus, the significance of this study is that it verified that VPEP-E can provide a foundation for preventing violence by promoting empathy among elementary school students, and the effectiveness of the program was improved through class-oriented activities and audio-visual educational methods.

DISCUSSION

The seriousness of the problem of violence due to the failure of overall respect for human rights has recently been pointed out in Korea. The necessity of approaching this problem from a human rights perspective, including human dignity and educational equality, has been emphasized [25]. To solve this problem, it is conceivable that Korean children need education to prevent violence. Educational programs were found to foster empathy and help children to prevent violence. By cultivating empathy in children, children react to the feelings of others and cooperate instead of engaging in violence [16]. Therefore, this study developed an educational program to prevent violence using empathy that can be directly implemented in the field and helps teachers educate elementary school students in the context of the persistent problem of childhood violence. This eight-session violence prevention program had the goal of contributing to the safety and health of children.

In this study, we developed VPEP-E using the analysis, design, and development phase of the ADDIE model. A literature review was conducted, expert opinions were incorporated into the program, and the theory of empathy was applied in each of the eight sessions. The formative evaluation comprehensively checked the effectiveness and efficiency of the training materials developed in the analysis, design, and development process, in addition to finding and correcting problems. In most previous studies on the prevention of violence against children, objective measurements of satisfaction were omitted, and only a comprehensive evaluation of the entire program was conducted [10,17]. Instead, this program developed in this study, which measured the satisfaction of elementary school teachers and actively reflected on the requirements of the program based on these findings, can be considered stable enough for future intervention studies.

As an educational strategy, Keller’s ARCS theory [21] was used to help learners prepare for the optimal psychological state in relation to past experiences. In addition, various methods were applied to maximize the learning effect. Attention was used by informing the students of the goal and using activities other than lectures, such as watching video clips. Relevance was applied by providing examples from elementary school students’ experiences or encouraging the students to think of examples themselves. Confidence makes learners believe that success is under their control. Activities that could be performed by the students themselves, such as quizzes, were applied to increase their confidence. Satisfaction reinforces the motivation for achievement through rewards. We therefore tried to improve satisfaction through games, encouraging students to express their opinions in discussions, and giving out peacekeeper awards. Therefore, the significance of this study is that it developed a variety of educational methods to prevent violence against elementary school students and found an appropriate method through verification.

In this study, Hoffman’s Empathy Theory [15] was used as a framework for preventing violence. The arousal patterns of empathy cause empathic distress and help a person to perceive others’ pain and respond empathically. Developing the ability to empathize with others’ difficulties helps prevent violence [26]. Mimicry was applied in the third session of this program to help students understand, distinguish, and express emotions through imitation and feedback. In the fourth and sixth sessions, classical conditioning and direct association were applied to provide students with an opportunity to practice reminding and empathizing with past experiences through clues, such as behavior and language. Mediated association, a reminder of one’s past experience by looking at clues arising from verbal mediation of information about the victim, was applied in the fifth and seventh sessions. Role taking was applied in the second and seventh sessions so that students could gain insights into others’ circumstances and think about how to solve problems as bystanders.

It is well known that empathy appears during the first 3 years of life and thereafter remains stable or develops gradually. Therefore, during the elementary school years, empathy may increase along with education. Lim and Kim [27] reported that young children’s sociality was promoted through an 8-week education program based on empathic understanding. Choi and Lee [17] described a violence education program targeting adolescents using empathy and found that their recognition and attitudes toward violence changed positively. Similar results were also shown in studies conducted in other countries. Koc’s study [16] revealed a significant negative correlation between tendency to violence and empathic ability. A study conducted among 62 Iranian sixth-grade elementary school students showed that a training program on empathy had a positive effect on reducing aggressiveness and increasing compatibility [28]. These results showed that enhancing students’ empathic ability can help them establish attitudes toward violence and prevent violence.

According to previous studies dealing with the relationship between empathy and violence, the effects of various types of empathy can be confirmed. specifically, since empathy motivates prosocial behavior and inhibits aggression, it may prevent violence [29]. Empathy facilitates altruistic behavior and a positive relationship with cooperative sociality, thereby leading to decreased aggression or antisocial behavior [15]. Therefore, the Korean Ministry of Education [5] proposed education that emphasize empathy as a fundamental countermeasure against violence. In a situation where there is a possibility of violence, it was found that if people have a high level of empathy, they support the victim by curbing the perpetrator’s behavior instead of being bystanders in a violent situation. In other words, it has been reported that the level of empathy determines behavior that prevents violence. Since empathy is effective in preventing violence, it is expected that the VPEP-E developed herein will also be effective.

Since the program developed in this study may be helpful for preventing violence among children, we hope to make it available to the target audience and make efforts to disseminate it in schools. Although this study focused on elementary school students, it is expected that violence prevention programs using empathy for children at various developmental stages will be developed based on this study. Additionally, since the content and methods of violence prevention change according to the times and social needs, efforts should be made to continue developing educational materials that can attract the interest of elementary school students and to disseminate the developed materials. Violence prevention education using empathy will be more effective if supported by legal and institutional support, such as mandating a longer duration of violence prevention education or establishing integrated educational methods.

This methodological study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. To develop the program, we used the three phases of the ADDIE model instead of conducting preliminary testing targeting the elementary school children. Of particular note, because the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, it was not possible to investigate students face-to-face or to hold in-person meetings. In addition, although this study proposes a new education program for preventing violence among children, it cannot be generalized because it was evaluated by a small number of elementary school teachers. Therefore, to address the limitations of the study, the effectiveness of this program should be evaluated through continuing interventional research among numerous elementary students across in regions. Children’s violence prevention programs using empathy should be expanded for various developmental stages of children or to provide differentiated education according to gender.

CONCLUSION

This study developed a violence prevention education program for elementary school students using empathy (VPEP-E), which is considered useful for elementary school students as it offers basic guidelines. Its reliability and feasibility were evaluated by experts. Therefore, we expect that it may contribute to preventing violence among elementary school students. Further research to measure the effectiveness of the VPEP-E is needed to generalize its reliability and validity. We also suggest that violence prevention programs using empathy should be expanded to include children in various developmental stages.

Notes

Conflict of interest

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.