Interventions to Reduce the Problems of Abused Children and Adolescents in Residential Facilities in South Korea: An Integrative Review

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to review the literature on intervention studies for abused children and adolescent in residential facilities in South Korea (ACARF-K). The goal was to understand the problems they experience, to evaluate the content and effectiveness of interventions applied to them, and to develop evidence-based nursing intervention programs.

Methods

We used four electronic databases to search for relevant articles. 18 studies according to Whittemore and Knafl's integrative review method to synthesize the literature.

Results

The ACARF-K experienced problems in biophysical, psychological, and sociocultural domains related to attachment impairment. Effective intervention strategies were building trust through empathy and fulfillment of needs, encouraging ACARF-K to express themselves and helping them to clarify emotions in an unthreatening environment, and improving their self-concept through activities in which they experienced achievement.

Conclusion

Interventions are needed to help restore attachment damage among ACARF-K. The interventions in this study utilized emotional, cognitive, relational, and behavioral therapeutic tools to improve their psychological and social capacities. Future intervention programs for ACARF-K should include these key elements.

INTRODUCTION

1. Need for Study

The number of reported cases of child abuse in South Korea almost doubled in 2 years from 11,715 in 2015 to 18,700 in 2016 and 22,367 in 2017 [1]. The number of abused children who die has also more than doubled in 2 years from 16 in 2015 to 36 in 2016 and 38 in 2017; thus, this is an important societal issue for which the government have prepared active countermeasures and ways to protect these children [1].

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines individuals younger than 18 as children and ‘child abuse’ as abuse and neglect of these individuals [2]. This definition of child abuse includes all behavior that exerts actual or potential harm on children's health, survival, development, or dignity, including physical and/or emotional unfair treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence, and commercial and other exploitation [2]. The South Korean Child Welfare Law also defines children as those younger than 18 [3]. Moreover, the law defines child abuse as harm to the health or welfare of children, physical/emotional/sexual violence toward children, as well as abandonment or neglect of children by adult including their caregivers [3].

Children most often experience abuse from their parents at home. According to a national report on child abuse from 2017, 80.4% of cases happened at home, and 76.8% of abusers were parents [1]. According to a national investigation on domestic violence from 2016, 27.6% of parents with children below the age of 18 responded that they abused their children within the past year. If unreported cases were accounted for, the actual rate would be even higher [4].

Care and love from family is vital not only for physical development of children but also for their cognitive and emotional development [5]. Therefore, children who are repeatedly exposed to distorted, dysfunctional interactions in their most intimate relationships experience various psychiatric, psychological, and social threats [6]. These children experience internalizing problems, such as anxiety, depression, and shame, due to unpredictable threats, suppression, and rejection, and they also often show externalizing problems, including anger and aggression [6,7]. These issues become internalized even after the abused children escape from their abusers and may continue into adulthood, adversely influencing their social adaptation [8].

Therefore, when child abuse is identified, various responses and protective measures are employed at the social level, and children are separated from abusive parents are enter child protection services. However, due to the emotional sequelae of abuse and the resulting behavioral issues, it is difficult for abused children to stay at general residential childcare facilities [1,9]. For these reasons, South Korean local governments and the Ministry of Health and Welfare operate residential facilities to protect abused children, such as temporary shelters for abused children and group homes, to protect children who are unable to stay with their caregivers or need to be rescued from abusers [1,9].

According to a report from 2017, approximately 973 abused children stayed at 60 temporary shelters for abused children [1], whereas 2,811 stayed at 533 group homes [9]. Abused children who stay at residential facilities for various reasons often experience serious sequelae of abuse and suffer losses resulting from separation from both parents [10]. In other words, these children are in an environment that is physically, psychologically, and socially different from that of abused children who live at home or those who stay away from abusers at a facility with another caregiver. Therefore, special help is necessary to resolve such difficulties for these children and to prevent issues in the future. For this, deep understanding of specific problems demonstrated by abused children staying at residential facilities without their parents is needed.

Studies that applied interventions for abused children and adolescents in residential facilities in South Korea (ACARF-K) reported positive effects of cognitive, emotional, and social aspects after art therapy [11], interpersonal relationship programs [12], and psychodrama [13]. However, since these studies provided interventions focused on a specific problem of abused children and reported effects of individual programs, they limit overall understanding of the problems experienced by ACARF-K, key aspects of interventions that led to positive changes, and changes resulting from the interventions.

Therefore, this study aims to systematically summarize the effects of various studies that applied intervention for ACARF-K; to this end, the methods of integrative review suggested by Whittemore and Knafl [14] were used. By investigating the problems experienced by ACARF-K, key aspects of effective interventions, and the effects of interventions, the present study aimed to prepare basic data to assist in the development of evidenced-based nursing interventions for ACARF-K.

2. Objectives

The purpose of this study was to integrally review interventional studies on ACARF-K living at child protection services, such as shelters for abused children and group homes.

The present study had the following specific goals.

Evaluate the characteristics and quality of selected studies.

Understand the problems experienced by ACARF-K.

Understand the interventions applied for ACARF-K.

Understand the effects of interventions provided to ACARF-K.

METHODS

1. Study Design

The present study was an integrative literature review of interventional studies on ACARF-K with an aim to understand the problems experienced by ACARF-K, organization of the provided interventions, and changes in ACARF-K observed as a result of interventions. Integrative review is a unique form of literature review that contributes to the production of new knowledge through comprehensive review, critique, and synthesis of literature on a specific theme [14]. In particular, since integrative review analyzes and evaluates various types of mutually exclusive studies, such as qualitative, survey, and experimental studies, and influences theoretical development and application in real life, it is appropriate to gain an overview of a specific theme [14]. The present study was conducted in the 5 stages of integrative review suggested by Whittemore et al. [14]. First, in the problem identification stage, the purpose of the study was clarified. Second, in the literature search stage, the scope of literature search and selection was limited based on the clarified study purpose. Third, in the data evaluation stage, studies that met the study purpose were selected. Fourth, in the data analysis stage, the primary data extracted from individual studies were comparatively analyzed and categorized according to the study purpose. Finally, in the presentation stage, the results were described comprehensively.

2. Study Question

The study question was the following: "What are the problems experienced by ACARF-K, key aspects of interventions that led to changes in ACARF-K, and changes resulting from the interventions?" For the literature search, keywords were selected according to Population (P) Intervention (I), Comparison (C), Outcome (O), and Study design (S) (PICOS), which is an evidence-based clinical criterion. The population (P) was ACARF-K; to include various participants, those between 7 years (about to start formal schooling) and 21 years (late adolescence) of age [15] were selected for this study. The intervention (I) referred to the interventions provided to ACARF-K, and there was no specific exclusion criterion regarding the number of sessions, duration, and type of interventions. There was also no limit on the time point at which the effects and variables were measured. The comparison (C) included experimental design and one group pretest-posttest design. The studies were not limited in the outcome variables (O) and the time at which these variables were measured. Also, Study design (S) was selected without restriction. Of these studies, studies for which the entire manuscript could be obtained in the analysis. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies on abused children living at home; (2) children living at residential facilities with their caregivers; (3) reason for staying at residential facilities is not abuse or unclear; and (4) protocols without results, editor's comments, literature for which the entire manuscript was not published, and review studies.

3. Data Collection

Studies that applied interventions for ACARF-K were collected from four South Korean databases, including DBpia, KISS, NDSL, and RISS, between April and May 2018. The keywords used for search were “abuse”, “abused”, “abandonment”, “neglect”, “domestic violence”, “group home (in Korean)”, “shelter”, “childcare facility”, “children”, and “adolescents”, and these keywords were combined using AND or OR. In order to include data that reflect the rapidly changing socio-cultural aspects and family environment in South Korea, studies published between January 2008 and April 2018 were included.

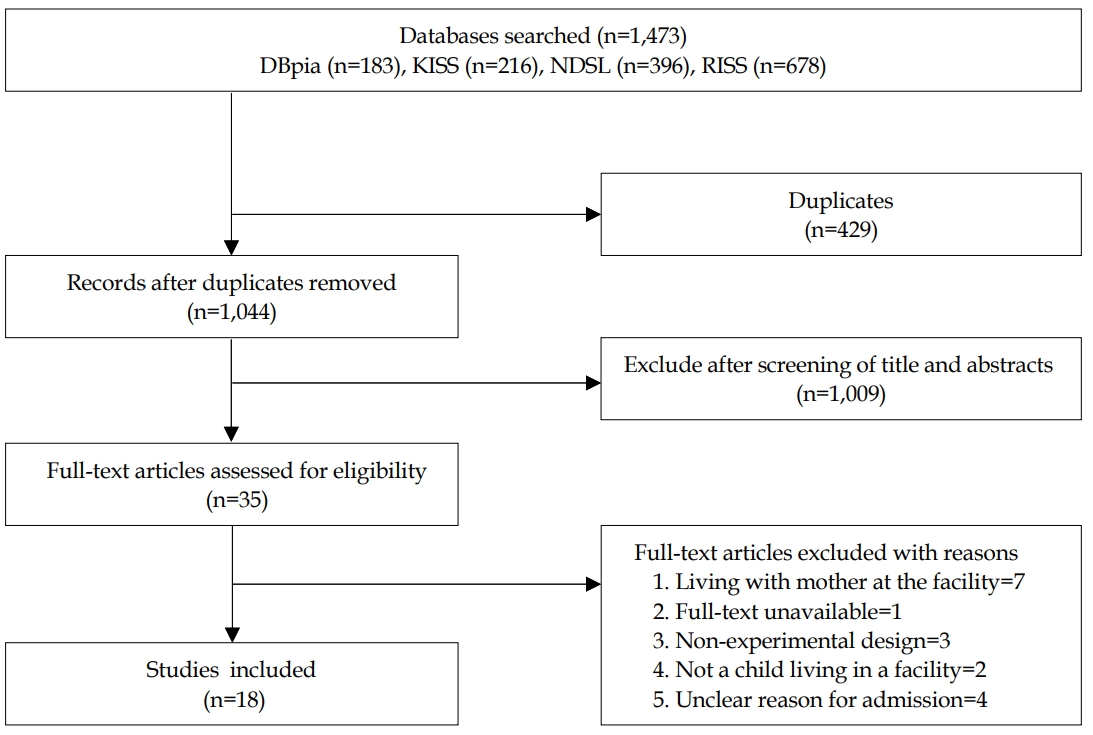

A total of 1,473 studies, including 183 from DBpia, 216 from KISS, 396 from NDSL, and 678 from RISS, were retrieved. Of these, 429 repeats and 1,009 that did not meet the selection criteria based on title and abstract were excluded, and entire manuscripts were obtained for the remaining 35. Of these, seven studies on children and adolescents living in residential facilities with their caregivers, one study for which the original manuscript could not be found, three non-interventional studies, two studies on abused children and adolescents living at home, and four studies where children and adolescents were staying at residential facilities for unclear reasons were excluded. As a result, a total of 18 studies were included for integrative review (Figure 1).

4. Qualitative Evaluation of the Selected Studies

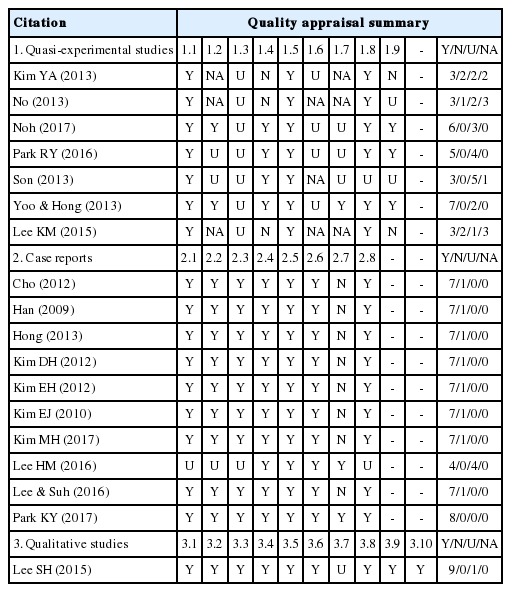

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [16] was used to evaluate the quality of the selected articles, which specified the analysis methods for different research design. Studies with quasiexperimental designs were evaluated through 9 criteria, case reports through 8 criteria, and qualitative studies through the 10 criteria of the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist [16]. Table 1 presents the results of the evaluation of the selected studies as “yes”, “no”, “unclear”, and “not applicable”(Table 1).

5. Data Analysis

The present study conducted the 4th stage of data analysis, suggested by Whittemore et al. [14], as follows. First, to understand the problems experienced by ACARF-K, three researchers investigated the characteristics of the children participating in the selected studies and identified all problems experienced by these children. Second, the identified problems were categorized based on similarity. Last, the categorized problems were labelled and structured as higher-level categories. The collected data were analyzed as explained below to understand the components of interventions applied to ACARF-K. Prior to starting data analysis, an analysis framework to extract five basic pieces of information about interventions-intervention type, intervention structure, key aspects and strategies used in interventions, intervention effects, and tools to measure the effects-was prepared through researcher meetings. Moreover, as supplementary data to aid the understanding of the basic data, study design, characteristics (sex and age) of the participants, and sample size (of the experimental group and control group) were also collected. Here, the Study Design Algorithm for Medical literature of Intervention (DAMI) was used for study design [17]. Based on this analysis framework, the three researchers individually performed primary analysis of the selected studies. Another researcher then performed secondary analysis of the studies, and whether the results of the primary and secondary analysis were consistent was confirmed. Agreement was reached on areas with differing opinions through discussion. For areas where agreement could not be reached, a professor in psychiatric nursing and a professor in pediatric nursing were consulted to obtain a conclusion. The primary and secondary analyses demonstrated that there were five key aspects of interventions: cognitive improvement, emotional regulation, relational improvement, behavioral modification, and provision of knowledge. Therefore, an analysis framework including these key aspects was prepared to comprehensively understand the five basic pieces of information about the interventions used by the selected studies.

RESULTS

1. Qualitative Evaluation of the Selected Studies

Of the 18 selected studies, seven were quasi-experimental studies, 10 were case reports, and one was a qualitative study. There were no randomized experimental studies. Seven or more “yes” answers to each evaluative criterion was considered to indicate “high quality”, four to six “moderate quality”, and three or less “low quality”. Of the seven quasi-experimental studies, one had high quality, two had moderate quality, and four had low quality (Table 1). Almost selected case reports and qualitative studies had high quality. In particular, with regard to the quality of research according to characteristics of studies, all seven quasi-experimental studies clearly presented the causes and results and measured the effects before and after the provision of the interventions. Moreover, one quasi-experimental study had follow-up tests (Table 2). Control groups were used in four out of seven studies; of these four, two confirmed pre-intervention homogeneity across groups, three used appropriate statistical methods. One study clearly indicated that they used identical methods to measure the effects across the groups, and no study provided detailed explanation of participant drop-outs and data treatment. For the 10 selected case reports, all used objective tools to measure emotions and behavior and provided changes before and after the interventions despite the small sample sizes. All 10 case reports clearly described the interventions provided during each session, and the qualitative changes observed as a result of the interventions were also described for each case. Nine case reports provided the general characteristics, past medical history, and current health status of the participants, and one out of these nine also described the unpredicted intervention effects and adverse effects. Although the selected qualitative study did not provide a clear explanation of the interaction between the researchers and participants, explanations of the philosophical view of the study, study questions, purpose, methodology, and data collection were clear and consistent. Furthermore, description of the data, analysis, and interpretation of study effects was consistent with the description of study methodology, and appropriate results representing the participants were deduced (Table 1). According to Whittemore et al. [14], low-quality studies selected for an integrative review are often assigned less significant values rather than being excluded. Based on this, the present study included all 18 studies in the analysis.

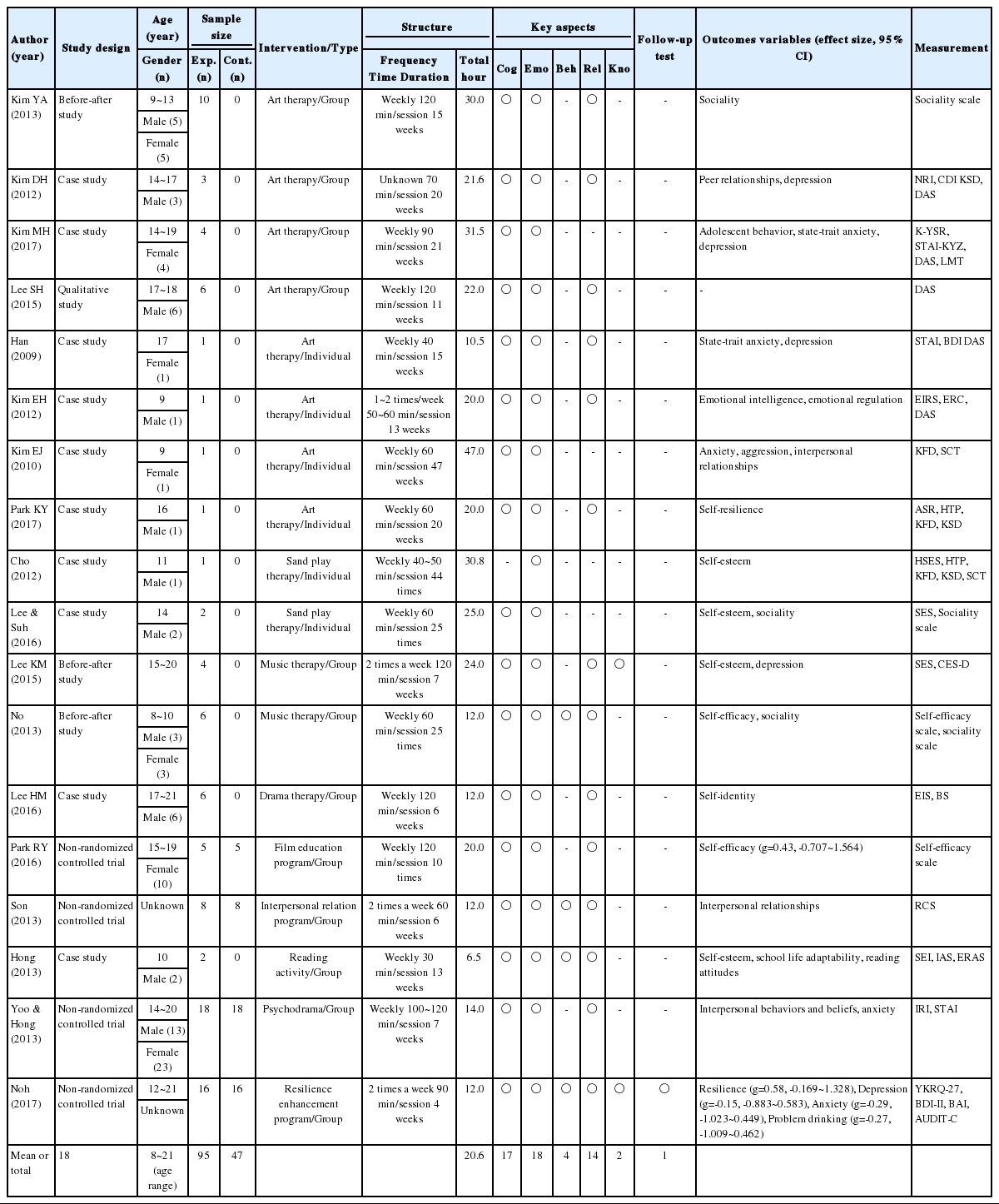

2. Characteristics of the Selected Studies

Two studies were published before 2010 (11.2%), eight between 2011 and 2014 (44.4%), and eight after 2015 (44.4%). Of these, six were published in journals (33.3%), and 10 were master's theses (55.6%). With regard to the researchers' areas of expertise, nine were in art therapy (50.0%), followed by four in social welfare and child welfare (22.2%), and one in nursing (5.6%). In terms of study design, the most common design was case report (n=10, 55.6%); seven were quasi-experimental design (38.8%) and one was qualitative research (5.6%) (Table 3).

A total of 142 ACARF-K participated in the 18 selected studies (95 in the experimental group and 47 in the control group). The age of the participants ranged between 8 and 21. Excluding 2 studies that did not report sex of the participants, of the remaining 94 participants, 47 were male and 47 were female. Seven studies were conducted with elementary school students (38.9%), two with middle school students (11.1%), and three with high school students (16.7%). The remaining six studies (33.3%) included adolescents and children starting formal schooling (Table 2) (Table 3).

3. Problems Experienced by ACARF-K

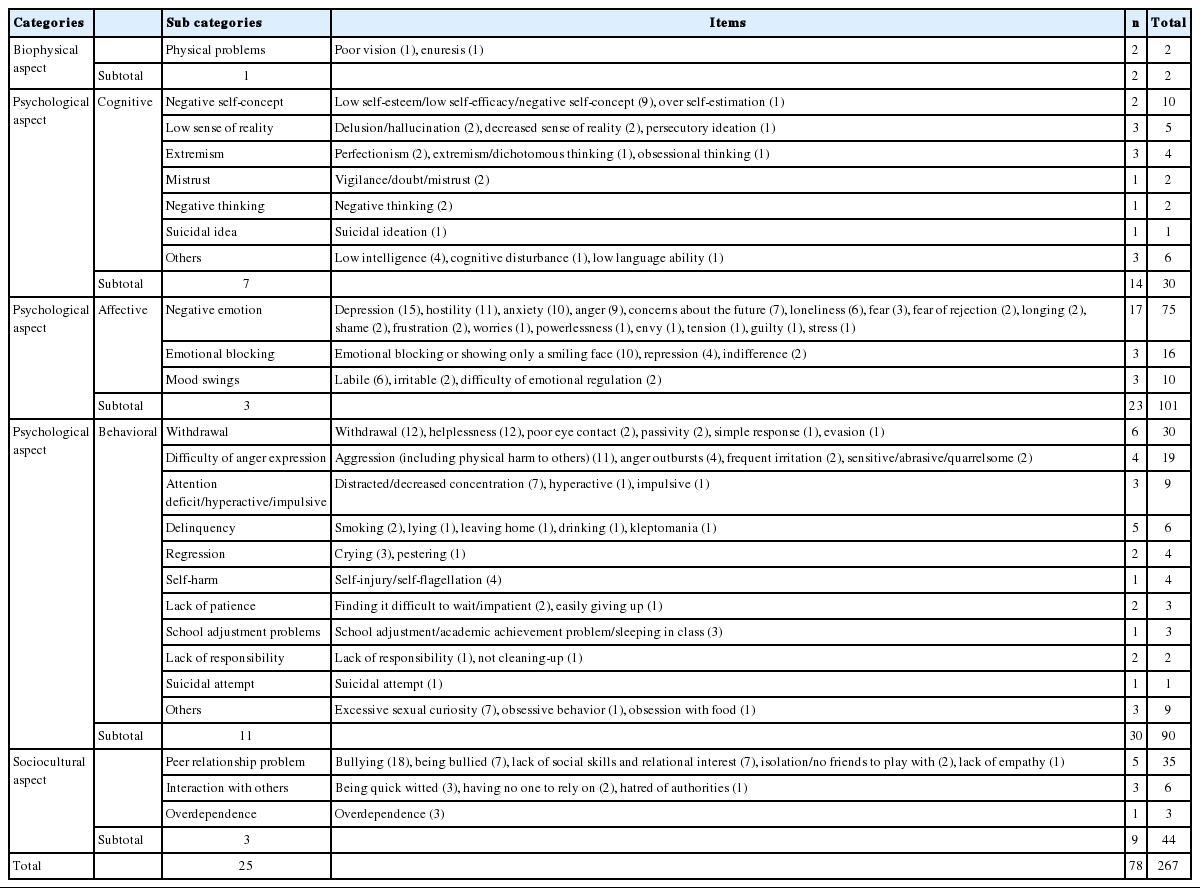

The following results were obtained from the analysis of problems experienced by ACARF-K. All 18 studies described the problems experienced by ACARF-K who were the targets of their interventions. In particular, case reports and qualitative studies provided detailed descriptions of the problems. When all of the described problems were extracted in the first stage, the exact terms used in the studies were used whenever possible, and this yielded a total of 267 problems. Subsequently, similar concepts were combined or grouped into higher-level categories comprising other sub-concepts, yielding a total of 25 categories. These 25 categories were further classified together into the following 3 factors: biophysical; psychological including problems in cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects; and sociocultural including relationship issues. In terms of the 267 problems collected initially, a minimum of one and a maximum of 17 problems were observed per child, with a mean of 4.8 problems per child (Table 4).

Of the 267 problems, only 2 were biophysical, 44 sociocultural, and 221 psychological; the psychological factor comprised a large variety of issues. Of the problems belonging to the psychological factor, 101 were affective issues, 90 were behavioral issues, and 30 were cognitive issues. In particular, affective problems were much more commonly related to negative emotion, including depression, hostility, anxiety, anger, concerns about the future, and loneliness, than to emotional blocking or mood swings. For cognitive problems, most were associated with negative self-concept including self-esteem and, self-efficacy followed by decreased sense of reality including delusions, hallucinations, persecutory ideation, and extremism. The most common behavioral problems were withdrawal and helplessness, and the second most common problem was expression of anger including behaviors that harm others. Other behavioral problems included the following: attention deficit and hyperactivity; delinquency including smoking, lying, and leaving home; regression; and self-harm (Table 4).

4. Interventions Provided to ACARF-K

The following results were obtained when the interventions provided to ACARF-K were analyzed in terms of intervention type, intervention structure, key aspects and strategies, intervention effects, and tools to measure the effects. The analysis included the study design, participant characteristics (age and sex), and sample size (of the experimental and control groups). The results are presented in Table 2.

1) Intervention type

In terms of intervention type, art therapy was the most common, used in eight studies, and two studies each used sand play therapy and music therapy. Six studies (33.3%) provided individualized intervention, and 12 studies (66.7%) used group intervention.

2) Intervention structure

The interventions were characterized by total intervention time, number of sessions, duration, and structure as outlined below. On average, total intervention time was 20.6 hours: 16.9 hours for group interventions and 25.6 hours for individualized interventions. Ten studies (55.6%) offered 11-20 intervention sessions, and 4 studies (22.2%) provided less than 10 sessions. In terms of the interval between intervention sessions, 13 studies (72.2%) provided weekly sessions, and 3 studies (16.7%) provided sessions twice per week. The interventions were provided for 1~3 months in 8 studies (44.4%) and for 4~6 months in 7 studies (38.9%). Each session lasted for less than 1 hour in 9 studies (50.0%) and for over 1 hours in 9 studies (50.0%). Most studies (n=15, 83.3%) used semi-structured interventions where the purpose and contents for each session were prepared in advance but participant activities or programs were carried out freely without a plan. Seven studies (38.9%) classified intervention stages into early, mid, and late, and 6 studies (33.3%) further classified intervention stages into 4 stages (Table 3).

3) Key aspects of interventions

In terms of intervention contents, the key aspects differed for different participant populations. Through primary and secondary analyses, the key aspects were grouped into 5 categories as follows: cognitive improvement, emotional regulation, relational improvement, behavioral modification, and provision of knowledge. These key aspects focused on resolving problems experienced by ACARF-K. Only one study organized their intervention focusing on one key aspect (emotional regulation). Three studies included cognitive improvement and emotional regulation, and 9 studies included cognitive improvement, emotional regulation, and relational improvement.

(1) Cognitive improvement

Cognitive improvement was used as a key aspect of interventions in 17 out of 18 studies. Cognitive improvement specifically includes self-understanding, improvement of self-concept, promotion of positivity, and future planning. First, self-understanding was the most commonly used factor, and methods such as recognition of irrationality, subconsciousness, identification of own problems (self-reflection), and exploration of ways to solve problems and necessary positive resources were used. Second, plays and art creation, which promote concentration, sense of accomplishment, and sense of affiliation, were used to improve self-concept, and these were used to promote confidence, self-esteem, self-identity, self-efficacy, and self-respect. Third, to promote positivity, interventions encouraged the participants to explore positive aspects of themselves and others; through this, the interventions aimed to form positive images of self and others, transform thinking into positive thinking, promote positive energy, and cultivate positive attitudes. Fourth, future planning was achieved through activities that lead to forming positive future images, finding hope, and recognizing future dreams. In addition, cognitive improvement included improvement of sense of accomplishment, attention, responsibility, trust, insight, and willpower, as well as forgiving and therapeutic transference.

(2) Emotional regulation

Emotional regulation was included in all 18 studies. Factors belonging to the emotional regulation category were emotional exploration, emotional expression, fulfilling needs, and finding a safe place. First, emotional exploration is a process during which participants explore their negative affectivity in a safe environment, and it aims to help participants understand negative affectivity, including anxiety and stress, as well as positive affectivity. Plays and group activities were used for individual and group interventions, and the importance of an empathetic, receptive attitude of the intervention provider toward the emotions expressed by ACARF-K was emphasized. Second, emotional expression refers to reflecting on and expressing one’s own emotions, and non-structured play therapy was the most common therapy used for individualized interventions. For group interventions, group projects involving theater plays, emotional thermometer, meditation, and bursting out anger were used often to help participants relieve negative emotions in a non-threatening way. All studies focused on forming trust between the intervention providers and ACARF-K in early stages of the intervention. For this, interesting activities to relax tension were used, including self-introduction through plays (games to open minds), making cheerful slogans, making self-introduction videos, and sharing thoughts. Third, basic needs were assessed and controlled by exploring safe places where ACARF-K would feel psychologically stable, by satisfying hunger, and by finding supporting resources. Even when the participants expressed their own emotions or anger excessively or did not want to participate in a given play, it was emphasized that their wishes were accepted.

(3) Behavioral modification and provision of knowledge

Behavioral modification was used in 4 studies. Behavioral modification included improvement of the ability to control oneself and modification of attitudes toward others. For improvement of the ability to control oneself, trainings were provided to set rules and adhere to them. For modification of attitudes toward others, accepting others' roles, learning about respect and amenability toward others, expressing gratitude, and adapting to rules during school classes were taught. Provision of knowledge was used in two studies; specifically, communicative strategies, such as expressing oneself, and progressive muscle relaxation training were provided.

(4) Relational improvement

Relational improvement was used in 14 studies. Factors belonging to the relational improvement category include understanding others, improving communication, strengthening group cohesiveness, promoting awareness of relationships, and asking for help. First, for understanding others, participants' empathy for others was promoted through increased awareness of others' emotions and needs. Second, for improving communication, education, and training on direct communicative strategies necessary in conversation with others were provided. Third, to strengthen group cohesiveness, activities such as making films and music band activities, which help participants to experience a sense of achievement through cooperation with others, were used, with an aim to improve teamwork, harmony, and thoughtfulness. Fourth, to promote the awareness of relationships, activities such as mapping interpersonal relationships, expressing gratitude, and finding others' good aspects were used to help participants recognize their interpersonal resources. Fifth, for the asking for help factor, activities involved listing ways to ask for help, interpersonal resources, and people who can provide help.

5. Intervention Effects and Tools to Measure the Effects

When the effect sizes were calculated, four of seven experimental studies lacked the necessary data for calculation of effect size, and one study inaccurately described its data. Moreover, two studies where the effect sizes could be calculated had different dependent variables. Table 3 shows the effect sizes calculated from these two studies.

The effects of the interventions were reported by evaluating (observing and measuring) changes in the problems experienced by ACARF-K. Most studies included in the present review evaluated the intervention effects in terms of changes in cognitive improvement, emotional regulation, and improvement of interpersonal relationships. Changes in cognitive improvement were evaluated in nine studies; changes in self-esteem, self-efficacy, and self-identity were evaluated through tools that measure self-concept and resilience. Self-esteem was the most commonly measured intervention effect, and four studies, including two that employed sand play therapy and others using music therapy and reading therapy, confirmed positive changes. Of these, two studies used the self-esteem scale (SES) [18,19]. Significant changes in self-efficacy were reported in two studies employing film education therapy and music therapy, and both studies used the self-efficacy scale [20].

Changes in emotional regulation were measured in seven studies, and the results confirmed that the interventions were effective. Of these seven, six confirmed positive changes in depression and anxiety. Of the studies that measured changes in depression and anxiety, five were case reports employing art therapy. Changes in depression were often measured using the Children’s Depression Inventory [10], and two studies used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [13] to measure anxiety.

A total of eight studies measured changes in relational improvement in terms of changes in sociality, relationship with friends, and interpersonal relationship techniques. Evaluation of interpersonal relationship techniques was the most commonly used evaluation (n=5), and all studies reported positive effects. Various tools, including the Sociality Scale [11] and Relationship Change Scale [12] were used to measure changes in relational improvement, and three studies employing art therapy measured changes in relational improvement.

Case reports using art therapy evaluated the effects of interventions through various projective test tools. Five studies used draw a story (DAS), and three studies used kinetic familial drawing (KFD) and kinetic school drawing (KSD). Two studies used sentence completion test (SCT) and house-tree-person (HTP)[21,22]. Moreover, three studies used DAS, a projective test tool, along with objective measurement tools in order to evaluate changes in depression and anxiety.

DISCUSSION

The significance of the findings of the present review of interventional studies on ACARF-K is discussed below. In terms of the quality of research, four out of seven quasi-experimental studies had low quality with scores of 3 or below. The areas with the lowest score were the establishment of a control group and statistical adequacy. Moreover, only one study observed long-term effects through follow-up tests. In contrast, case reports and qualitative studies had high quality scores in most areas.

The low scores of experimental studies on the establishment of control groups may be attributed to the difficulties in finding large samples, given that many temporary shelters for abused children and group homes are small in scale, with 5-8 individuals living at a place [1,9]. Moreover, since ACARF-K are vulnerable individuals who require protection, access to potential participants may also have been limited. However, to find scientific evidence for interventions provided to ACARF-K, future studies will need to satisfy the following: establishment of control groups, randomized group assignment, evaluation of long-term effects, evidence-based calculation of sample size, and adequacy of statistical analysis.

Interventional studies on ACARF-K were mostly conducted in the realms of art therapy, including fine arts, music, and film education. The acceptance of interventions may have been a reason why the studies most commonly employed art therapy. For instance, symbolization, which is often used in art therapy, is very useful as a mediator that encourages children to transfer and express their emotions toward their parents to other non-threatening subjects; thus, it would have been easy for ACARF-K to accept [10,18]. Nevertheless, considering that ACARF-K experience various complex biophysical, psychological, and sociocultural problems and that long-term measures, including resources in local communities, are necessary to provide effective help, interventional studies for ACARF-K should be conducted in various areas with comprehensive, multi-disciplinary approaches. Effect sizes could be calculated in only two quasi-experimental studies because many studies did not have control groups and described statistical methods without sufficient details or inaccurately. In order to objectively evaluate the effects of interventions, it is helpful to calculate and compare effect sizes. Therefore, researchers should make accurate reports of study results and calculate effect sizes for publication as they have access to the original data.

Affective problems were most common in ACARF-K, followed by behavioral, cognitive, relational, and biophysical problems. Particularly, the primary response to experiences of abuse and separation from parents manifested as affective problems. Of such affective problems, negative emotion such as depression, hostility, anxiety, concern, and loneliness was common, indicating that ACARF-K experience difficulties in regulating their emotions. Such psychological characteristics of ACARF-K are similar to those of reactive attachment disorder, which is characterized by emotional suppression, depression, severe anxiety, and fear [5]. This can be interpreted to represent that ACARF-K experience difficulties due to attachment impairment. In this way, the findings of this study are consistent with those of Jeong [23] who reported that ACARF-K have difficulties in forming secure attachment and often have avoidant attachment as a result of attachment impairment. In other words, since various problems observed in abused children stem from attachment impairment in the relationship with primary caregivers, impaired attachment should be recovered through stable relationships. This is in line with the suggestion of Jeong [23] that abused children often have avoidant attachment and require continued relationships with stable individuals for recovery. Attachment impairment due to abuse has a negative impact on self-concept formation, which adversely affects attachment in adulthood [24]. Therefore, multi-disciplinary approaches as well as social support and interventions for problems arising from attachment impairment are required for abused children.

Within the affective factor, the emotional blocking category was the second most common, indicating that ACARF-K rarely had their negative affectivity accepted or empathized with by others [6,7,23]. When negative emotion cannot be reduced due to a lack of appropriate coping resources to regulate emotions, it becomes more likely that it will suppress rational thinking and lead to behavioral issues [5,7]. Therefore, interventions focused on affective problems identified in this study should be developed and applied, which is in line with the findings of Han [25] who emphasized the need for interventions for emotional regulation of ACARF-K.

In terms of behavioral problems, withdrawal and helplessness were the most common, while other types of problematic behavior such as expression of anger and delinquency were also observed. These findings support the results of Dackis et al. [7] who reported that ACARF-K experience problems in emotional regulation and emotional suppression, as well as behavioral issues such as aggressivity. ACARF-K have lowered self-esteem from abuse and exhibit withdrawal, but they also explode in anger in front of other weaker individuals; this can be explained as aggressive expression of frustration from abuse [6]. In other words, internalizing problems experienced by ACARF-K, such as depression and anxiety, accelerate withdrawal behavior and interfere with social adaptation, while anger increases externalizing problems, such as aggression [6,7]. Therefore, emotional problems should be resolved first to prevent and improve behavioral issues [5-7]. This is in accordance with Schoorl et al. [26] who reported that ACARF-K who show attention deficit and hyperactivity, delinquency, lack of patience, and lack of responsibility are at high risk of progression into psychiatric disorders such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder or conduct disorder, which indicates the need for interventions for emotional and behavioral regulation in ACARF-K.

In the cognitive domain, lowered self-concept was found to be a typical problem experienced by ACARF-K due to psychological withdrawal as a result of chronic, repeated suppression, rejection, and insults from their abuser [6]. Lowered sense of reality, such as delusions, hallucinations, and persecutory ideation, were also reported in the interventional studies in this review, reflecting the severity of problems experienced by ACARF-K. In general, decreases in self-concept and sense of reality, such as delusions, hallucinations, and persecutory ideation, are based on negative affectivity including shame and guilt [5]. Considering this, emotional interventions should also be provided for cognitive recovery.

In terms of relationship issues, the most common issue reported was with regard to relationships with friends. In particular, it is noteworthy that ACARF-K reported to be twice as likely to abuse others than to be abused by others. This is similar to the findings of Dackis et al. [7] that abused children have blunt responses to stressors and suppressed normal responses, which leads to callous unemotional traits that prevent them from paying attention to warning signs, thus increasing the possibility of behavioral problems. This is similar to the callous traits observed in anti-social personality disorder [7] and indicates that behavioral issues of ACARF-K may potentially evolve into societal issues. Accordingly, to develop more social interest and interventions are required for problems experienced by ACARF-K.

Anxiety and concerns about the future were also reported in studies. Considering that ACARF-K are likely to face many difficulties when adapting to society after leaving residential facilities [8], realistic systematic strategies and measures would be required in many areas [12]. Furthermore, rather than temporarily decreasing anxiety and concerns about the future through distraction therapy, children should be helped to explore and plan their future on a realistic basis, as suggested by Kim [11], Park [20], and Worsley et al. [27]. Only two cases of biophysical issues were reported; this seems to have been because most problems reported by ACARF-K or observed in them were emotional-behavioral issues, as well as because biophysical issues were not the interest or focus of the researchers and thus left unreported.

Moreover, affective, cognitive, behavioral, and relational issues were not mutually independent but rather interacted with one another in a circular pattern. Therefore, rather than focusing on a given area, it will be necessary to provide systematic interventions based on deep understanding of various problems experienced by ACARF-K.

When the key aspects of interventions provided to ACARF-K were classified and reviewed in the 5 domains of cognitive improvement, behavioral modification, emotional regulation, provision of knowledge, and relational improvement, cognitive improvement and emotional regulation were the most commonly used key domains. For these, activities promoting self-understanding and emotional expression were most often used, with effective outcomes. The fact that negative affectivity was relieved through self-understanding and emotional expression suggests that ACARF-K learned to reflect on themselves while understanding and exposing their internal conflicts and is in accordance with a previous report [21] that self-understanding and emotional expression are helpful in decreasing negative affectivity. Moreover, the finding can also be explained as follows: when their emotions were accepted by others without criticism, ACARF-K would have experienced relief of negative affectivity [21].

In order to promote social competency, behavioral modification and relational improvement were used. Behavioral modification was often used in group interventions; for example, participants set and adhered to their own group rules, to learn to regulate their own behavior and treat others with respect [12]. This process was designed to improve ACARF-K's social adaptation by helping them to gradually learn socially acceptable behavior [12]. However, of the studies selected for this review, only a few clearly described that behavioral modification was an intervention strategy. This seems to be because the studies focused on emotional regulation and cognitive improvement rather than behavioral modification. Only two studies applied provision of knowledge, and these studies used provision of knowledge as a means of emotional expression and self-presentation rather than as the main focus.

In terms of relational improvement, relief of negative affectivity led to transfer of ACARF-K's interest to other individuals. Here, emotional relief led to psychological relaxation, thus helping ACARF-K to become less self-centered with their thoughts and more oriented toward other individuals [10]. In other words, the finding indicates that overcoming negative affectivity has an important correlation with improvement of social competency. Moreover, group interventions were more common than individualized interventions for older participants, and intimacy and group cohesiveness were increased through group interventions, fulfilling the participants' need to seek sense of affiliation [5,10]. In addition, group interventions were shorter than individualized interventions, and the total number of sessions was also fewer for group interventions. This may have been because of difficulties in managing groups for a long time but more likely because of the characteristics of group interventions where the dynamic environment of a group further promotes the positive effects of interventions.

None of the selected studies set improvement of biophysical problems as a goal of their interventions. However, cultivating physical capacities is also important for balanced growth and development of ACARF-K [5,28]. Since emotional and behavioral problems often manifest as physical or physiological problems in children, interventions for these aspects would also be important [5]. Furthermore, since physical activity helps to release emotions and promotes the secretion of neurotransmitters, thus helping to maintain positive thinking [5,28], various interventions that can improve physical capabilities should also be provided in the future.

Intervention strategies emphasized in interventional studies with ACARF-K can be summarized as follows. First, to help ACARF-K with attachment impairment to form trust with others, the importance of the attitude of the intervention provider as a therapeutic tool was emphasized. The intervention provider should possess an open attitude based on deep understanding and empathy toward the needs of children. Moreover, fulfilling these needs holds an important significance in the early stages of intervention since interventions may be understood to be forceful when demands are not met or declined, as suggested by Kim [21]. Therefore, the intervention provider should understand and mediate the needs of children based on empathy and should be able to place limits on destructive behavior.

Second, safe activities that promote emotional relief should be provided. ACARF-K tend to be shy as they are not used to expressing their emotions [23]. Furthermore, conflicts among participants may be present due to differences in the time at which they entered the residential facilities and their ages [13]. Plays relax tension and allow participants to exhibit creative competency on a level playing field [21]. These findings are also substantiated by the results of Choi and Cho [29], and Cattanach [30] who reported that activities including plays are effective in helping participants to change negative affectivity, accept the intervention provider, learn group rules, and cultivate a sense of affiliation. Moreover, when the intervention provider also participates in plays, it may help to correct negative perceptions of authority figures through therapeutic transference [5]. In this regard, art therapy is a good tool to help abused children safely express their emotions, and is fun for children [21]; therefore, the authors suggest applying art therapy in interventions.

Third, activities where the participants can focus and experience a sense of accomplishment are required [18,20]. Since experiences of living at residential facilities may lead to withdrawal and suppression of personal character due to group environments, abused children may have lower self-esteem [10]. Experiences of successful accomplishment are helpful in improving self-concept, including self-esteem [18]; thus, it is necessary to reflect this in interventions for ACARF-K.

In order to confirm the effects of interventions, changes in cognitive improvement, emotional regulation, and relational improvement in ACARF-K were evaluated in most studies; the tools used for this included objective and projective tools. Level of anxiety was the most commonly used variable to measure changes in emotional regulation. Since ACARF-K may feel anxious due to a lack of trust in others, it seems reasonable that level of anxiety would be used to measure the effects of the interventions in terms of emotional regulation. The STAI developed by Spielberger was the most commonly used scale to measure anxiety.

In terms of changes in cognitive improvement, Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale was used often [19]. No tool was used to evaluate improvement of cognitive issues experienced by ACARF-K. Future studies should evaluate tools that can systematically measure changes in negative self-concept or decreased sense of reality, which are commonly observed.

The DAS was the most commonly used projective tool. Other tools were used as well, presumably because using quantitative tools to evaluate changes in participants would have been limited by the small sample sizes. Moreover, projective tools would have been used to evaluate psychological changes that cannot be evaluated with quantitative tools. However, projective tools are influenced by the subjectivity of the evaluator, and also provide limited scientific evidence. Therefore, future studies should use projective tools in conjunction with objective measurement tools.

Although the present review included grey literature to decrease publication bias, only a few experimental studies were used, and effect sizes could be calculated from only a small number of studies, thus limiting direct comparisons. In addition, only interventional studies on ACARF-K who were currently under protection at residential facilities due to abuse were included in the review, and the type of abuse was not categorized. Therefore, in order to overcome these limitations, the authors make the following suggestions. First, studies should investigate differences in issues experienced by non-abused children, who were excluded from this review, and abused children. Moreover, studies reporting on effective interventions for issues experienced following different types of abuse should be investigated. Further, additional interventional studies with a scientific experimental study design should be conducted to help ACARF-K recover from impaired attachment, improve their relationships with others, and regulate their emotions and behavior.

The present study reviewed various interventional studies with ACARF-K and investigated the issues experienced by ACARF-K and key aspects of interventions that led to changes in ACARF-K. General surveys are not useful to comprehensively understand the issues experienced by ACARF-K. The present study is significant in that it reviewed previous literature on ACARF-K to understand their common issues and collectively presented these issues in terms of biophysical, psychological, and sociocultural factors. In addition, a systematic analysis framework was used to analyze the interventions provided to ACARF-K to prepare basic data to develop interventions for ACARF-K. In particular, since the type and structure of interventions, key aspects of interventions, and measurement tools used to evaluate effects of interventions were presented systematically, the results of this review will be useful in designing interventions and future studies.

CONCLUSION

The present study is an integrative literature review of interventional studies on ACARF-K conducted to understand the problems experienced by ACARF-K and the interventions that led to changes in ACARF-K. The review revealed that ACARF-K experienced attachment impairment as well as various psychological and sociocultural problems. The key aspects of interventions provided to improve psychological and sociocultural functioning of ACARF-K were “cognitive improvement”, “emotional regulation”, “relational improvement”, “behavioral modification”, and “provision of knowledge”. Through these, the interventions led to positive effects in improving negative affectivity, self-concept, and interpersonal relationships of abused children. Moreover, the key aspects of interventions that led to changes in issues experienced by ACARF-K were the following: forming trust based on empathy and acceptance of demands; provision of safe activities that promote emotional relief; and provision of activities where ACARF-K can focus and experience a sense of accomplishment. The role of the intervention provider as a therapeutic tool was also emphasized. Future studies that organize intervention programs for ACARF-K are encouraged to utilize the key aspects and interventional strategies found in the present review.

Notes

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

Appendices

Appendix

Citations for Studies Included in this Study

1. Kim YA. Effects of group art therapy on the sociality of abuse children. Korean Journal of Art Therapy. 2013;20(4):791-809.

2. Kim DH. A case study of group art therapy for improved relationship and reduced depression of dwellers in the youth shelter. The Korean Journal of Arts Therapy. 2012;12(2):37-65.

3. Kim MH. A case study on the group art therapy of adolescent who experienced domestic violence: Impacts of anxiety and depression [master's thesis]. Seoul: Dongguk University; 2017. p. 1-92.

4. Lee SH. Phenomenological study of the experience of group art therapy group home youth [dissertation]. Gyeongsan: Yeungnam University; 2015. p. 1-195.

5. Han S. The effects of Mandara art therapy on abused student anxiety depression. Art and Design Research Institute. 2009;9(2):1-32.

6. Kim EH. The effect of therapy on emotion regulation competence of group home children [master's thesis]. Gyeonggi: Hansei University; 2012. p. 1-116.

7. Kim EJ. The case study of art therapy for families of abused children' Anxiety: On the basis of Kohut's self psychology [master's thesis]. Seoul: Myongji University; 2010. p. 1-73.

8. Park KY. The influence for art therapy on resilience of teenagers living in shelter: A single case study [master's thesis]. Seoul: Ewha Woman University; 2017. p. 1-107.

9. Cho DN. The effect of sandplay therapy on self-esteem of children with abuse and negligence: A case of children living in child group home [master's thesis]. Gyeongsangnam-do: Kaya University; 2012. p. 1-92.

10. Lee M, Suh H. A study of sand play therapy for children exposed to the sex by their parents: Focusing on self-esteem and sociality. Journal of Open Parent Education. 2016;8(2):91-110.

11. Lee KM. Effect of a band activity on the self-esteem and depression for the male adolescents in the youth shelter for mid and long term period [master's thesis]. Seoul: Myongji University; 2015. p. 1-83.

12. No CD. A study on the effectiveness of program to improve the self-efficacy and sociability of group home children: Focusing on music therapy program [master's thesis]. Jeollanam-do: Mokpo University; 2013. p. 1-106.

13. Lee HM. Case study of dramatherapy which affects in identity establishment of youths in youth shelter [master's thesis]. Gyeonggi: Yongin University; 2016. p. 1-101.

14. Park RY. A study on the effect of film education program on self-efficacy of adolescents at risk outside the home: Focusing on youth shelters [master's thesis]. Seoul: Sejong University; 2016. p. 1-81.

15. Son KS. Development of program and its assessment for improving interpersonal relationship of children hurt by domestic violence. Journal of Future Social Work Research. 2013;4(1):5-42.

16. Hong SM. Case study on the changes of self-esteem and school adjustment of group home primary school children through picture book reading [master's thesis]. Chungcheongbuk-do: Chungbuk University; 2013. p. 1-112.

17. Yoo HA, Hong HY. A study of psychodrama effect on interpersonal relationship and anxiety for adolescents in the youth shelter for mid and long term period. Korean Journal of Youth Studies. 2013;20(4):97-124.

18. Noh D. Development and evaluation of a resilience enhancement program for shelter-residing female youth [dissertations]. Seoul: Yonsei University; 2017. p. 1-90.