Influence of Achievement Motivation and Parent-Child Relationship on Ego Identity in Korean Nursing Students

Article information

Trans Abstract

Purpose

This study was conducted to characterize the influence of achievement motivation and the parent-child relationship on ego identity in Korean nursing students.

Methods

The participants were 217 Korean nursing students in the first and fourth year of university. Data were collected through self-report questionnaires composed of items assessing ego identity, achievement motivation, the parent-child relationship, and demographic characteristics. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, one-way analysis of variance, the x2 test, and multinomial logistic regression analysis.

Results

Ego identity was related to achievement motivation; moreover, the achievement motivation of students with moratorium and achieved identity status was significantly higher than that of students with low-profile moratorium and diffused identity statuses. Ego identity was not related to the mother-child relationship, but the father-child relationship of students in foreclosure was significantly higher than that of students with diffused identity status. The factors influencing achieved identity compared to diffused identity were achievement motivation, year in school, satisfaction with school, and having religious beliefs.

Conclusion

These findings indicate that nursing students’ ego identity attainment was more influenced by achievement motivation than by the parent-child relationship. It emphasizes that highly motivated students can develop their own identities regardless of the parent-child relationship.

INTRODUCTION

Nursing students who understand their own abilities, dispositions, and values are able to have a clear concept of themselves and their nursing careers [1]. This can be possible owing to the formation of ego identity. Ego identity is the view of one’s own self; it refers to an awareness of individual uniqueness, a sense of continuity of personal character, and maintenance of binding with a group’s ideals [2].

Identity formation is known to be a developmental task in the period of adolescence and early adulthood [2-4]. Many researchers have suggested that individuals form ego identity during their time at university, as that is the transitional period between adolescence and adulthood [5,6]. University students experience sudden situational changes, and are confused by new responsibilities, but struggle to make resolutions [5,7].

Antecedent studies reported that young people who achieved their own identities were inclined to pursue career development [6,8-10], but youths who did not figure out their identities could not gain good results in either education or work [11]. Hence, identity formation was reported to be a precious personal resource to become a professional [9]. Therefore, ego identity achievement is important for nursing students to be professional nurses who understand their own abilities and make efforts to develop their careers [6].

Many researchers presented that ego identity developed with progressive changes [4,5]. Erikson [2] proposed that youths tried to move beyond diffused identity for achieved identity. Marcia [7] added two intermediate statuses (foreclosure and moratorium) to Erikson’s polar identity statuses (diffused identity and achieved identity) [2]. Marcia [7] used the two dimensions of exploration and commitment to distinguish four identity statuses, including diffused identity, foreclosure, moratorium, and achieved identity. Diffused identity is characterized by low in exploration and lack of commitment, therefore individuals with diffused identity have no interest in choosing among alternatives and don’t make commitments [12]. Foreclosure is featured as being low in exploration but strong in commitment, thus foreclosed individuals don’t experience exploration, and subsequently accept the decisions of their parents and significant others [7]. Moratorium is defined as being high in exploration but unstable in commitment, so individuals with moratorium actively struggle to choose among options, but don’t commit to them [7]. Achieved identity is characterized by strong commitment after sufficient exploration, therefore individuals with achieved identity commit to a determined option after experiencing crisis while exploring options [12]. Marcia [7] proposed that individuals be faced with the two dimensions of exploration and commitment in two areas of ideology and occupation.

The formation of ego identity is a continuously dynamic process that is greatly based on sociocultural context [13]. Family support is an important and powerful contextual factor. The effect of parental relationship on adolescents’ identity formation has been supported [14]. Parental involvement and warmth was positively correlated with career development, but authoritarian parenting was negatively related to career development [15]. Moreover, parental influence on vocational identity formation in college students could vary by cultural context, especially for individuals in collectivist cultures including South Korea, who tend to prioritize family needs and parental values over personal preferences [16]. Therefore, research into the influence of the parent-child relationship on ego identity in Korean nursing students is needed to verify that family support affects ego identity development in Korean youths.

Ego identity development has been shown to be influenced by intrapersonal characteristics [3]. Adaptive behaviors or well-established concepts seem to be driven by not only environmental conditions but personal factors, including intentions to achieve and advance [17]. This driving force is called ‘achievement motivation’, and stimulates a person to action toward a goal; accordingly, it is important for goal attainment and task fulfillment [18]. Achievement motivation is known to have several characteristics composed of wholehearted devotion to doing work, hope to succeed, taking risks, and the belief in one’s competence [19]. Personal intrinsic motivation in the decision making process was important to forming an adequate identity, because individuals can attain their ego identity when they try to act toward an outcome, for example, choosing alternatives and committing to a decision. It was suggested that personal intrinsic motivation had an essential role in vocational identity development of college students [16]. Furthermore, students with valuable intrinsic characteristics such as motivation could advance their vocational identities in spite of poor family relations [16]. For this reason, this study investigated the influence of achievement motivation on ego identity formation in Korean nursing students.

Studies on ego identity reported that women had more advanced identity than did men [5,20], and senior students had more advanced identity than did students in lower grades [4,6]. Moreover, research showed that identity development was related to socioeconomic status, including family income and parents’ educational level [6,13].

Thus, this study was conducted to characterize the influence of achievement motivation and the parent-child relationship on ego identity in Korean nursing students. Specifically, the first purpose of this study was to investigate ego identity in connection with achievement motivation and the parentchild relationship. The second purpose was to look over ego identity in regard to demographic characteristics. The third purpose was to investigate factors influencing ego identity of Korean nursing students.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional descriptive study to determine the influence of achievement motivation and the parent-child relationship on ego identity in Korean nursing students.

2. Setting and Samples

This study was conducted in D city, South Korea on a convenience sample of nursing students who attended one nursing school and voluntarily gave written permission to participate. The participants were 217 nursing students in the first and fourth year of university. The sample size for multinomial logistic regression was calculated as 210 using the G*Power 3.1.9 program to attain a significance level of .05, a power of .80, and a medium effect size (odds ratio) of 1.5 [21]. The investigation was done with 230 nursing students considering a potential dropout rate of 10%. Of the 225 nursing students who returned questionnaires (response rate 97.8%), eight students were excluded because four students did not answer both items of the mother-child relationship and the father-child relationship, and four students did not answer completely, so 217 students were included in the data analysis.

3. Measurements

1) Ego identity

Ego identity was measured using the Korean version [22] of the Extended Objective Measure of Ego Identity Status II (EOM-EIS II) [23]. The EOM-EIS II was translated into Korean, and provided acceptable reliability and validity in Korean university students [22].

The scale includes 64 items consisting of two areas divided into 32 ideological items and 32 interpersonal items. Ideological items include four subjects divided into occupation, religion, politics, and philosophical lifestyle, which have eight items each. Interpersonal items include four subjects divided into friendship, dating, sex roles, and recreation, which also have eight items each. Each of the ideological and interpersonal subjects consists of four dimensions divided into diffused identity, foreclosure, moratorium, and achieved identity, which have two items each. Each item is scored on a 6 point Likert type scale (1=strongly disagree, 6=strongly agree).

Scores of the four dimensions (diffused identity, foreclosure, moratorium, and achieved identity) are summed in all of ideological and interpersonal subjects, and then means and standard deviations of each of those four dimensions are calculated. Cutoff points for each of the four dimensions are computed by adding the mean to 0.5 of a standard deviation according to revised classification criteria [24]. Therefore, students scoring beyond a higher cutoff point on a single dimension were grouped into a status of that dimension. However, students scoring beyond higher cutoff points on two or more dimensions were grouped into a less developed status (diffused identity, foreclosure, and moratorium). Additionally, students scoring at lower cutoff points on all dimensions were grouped into the low-profile moratorium.

The Cronbach’s α values for diffused identity, foreclosure, moratorium, and achieved identity in Shin’s study [22] were .76, .87, .70, and .79, respectively. The Cronbach’s α values for diffused identity, foreclosure, moratorium, and achieved identity in this study were .73, .85, .69, and .80, respectively.

2) Achievement motivation

Achievement motivation was measured using the Achievement Motivation Scale for university students and adults, and provided acceptable reliability and validity in Korean university students [19].

The scale includes 28 items consisting of four dimensions divided into passion (11 items), hope (7 items), adventure (6 items), and self-confidence (4 items). The items of the passion dimension express wholehearted devotion to doing work, and the items of the hope dimension indicate that desire will be realized, or needs will be fulfilled [19]. The items of the adventure dimension present taking risks in the expectation of good results, and the items of the self-confidence dimension indicate the belief in one’s own ability, or strong feelings of trust in one’s competence for work [19]. Each item is scored on a 5 point Likert type scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree), and total scores range from 28 to 140. Higher scores mean that a person is deeply motivated to achieve tasks.

In Lim and Kang’s study [19], the Cronbach’s α for total items was .93, and the Cronbach’s α values for each of the four dimension (passion, hope, adventure, and self-confidence) were .87, .83, .81, and .77, respectively. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for total items was .94, and the Cronbach’s α values for passion, hope, adventure, and self-confidence dimension were .87, .88, .76, and .82, respectively.

3) The parent-child relationship

The scale for the parent-child relationship was the Parent-Child Relationship Scale for university students and adults, and provided acceptable reliability and validity in Korean university students [25].

The scale includes 40 items consisting of two areas divided into 20 mother-child relationship items and 20 father-child relationship items. The two areas include four dimensions divided into closeness (7 items), devotion (6 items), respect (4 items), and strictness (3 items). The items of the closeness dimension express feeling an affinity for parents, or belonging together, and the items of the devotion dimension indicate the recognition of parents’ concern and self-sacrifice for their children [25]. The items of the respect dimension express an admiration for parents, or feeling high regard for their parents, and the items of the strictness dimension present that parents demand accurate attention to rules, or impose rigorous discipline on their children [25]. Each item is scored on a 6 point Likert type scale (1=strongly disagree, 6=strongly agree), and total scores of each area range from 20 to 120. Higher scores mean that the characteristic of each dimension is higher.

In Choi’s study [25], the Cronbach’s α for total items of the mother-child relationship was .91, and the Cronbach’s α values for each dimension (closeness, devotion, respect, and strictness) were .88, .83, .77, and .70, respectively, while the Cronbach’s α for total items of the father-child relationship was .93, and the Cronbach’s α values for closeness, devotion, respect, and strictness were .89, .87, .83, and .74, respectively. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for total items of the mother-child relationship was .82, and the Cronbach’s α values for closeness, devotion, respect, and strictness were .88, .83, .77, and .71, respectively, while the Cronbach’s α for total items of the father-child relationship was .87, and the Cronbach’s α values for closeness, devotion, respect, and strictness were .90, .88, .84, and .79, respectively.

4. Data collection

Data were collected from May 11th to May 20th, 2016. After gaining approval from the chair of a nursing school, the survey was conducted with 225 nursing students, who willingly agreed to take part in this study. Participants were requested to fill out a questionnaire composed of items assessing ego identity, achievement motivation, the parent-child relationship, and demographic characteristics. The average response time of participants was approximately 30 minutes.

5. Ethical considerations

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (CUIRB-2016-0029). Participants were given explanations about the purpose and intent of this study. In addition, participants were informed that their responses would be dealt with anonymously and confidentially, and that they could withdraw from this study whenever they wished to do so. Participants voluntarily gave written permission to participate.

6. Data analysis

The data were analyzed with SPSS version 19.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL, USA). Ego identity, achievement motivation, the parent-child relationship, and demographic characteristics of students were analyzed with descriptive statistics. The differences in achievement motivation and the parent-child relationship according to ego identity were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance. The relationship between ego identity and demographic characteristics were analyzed with the x2 test. Factors influencing ego identity of students were determined using multinomial logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS

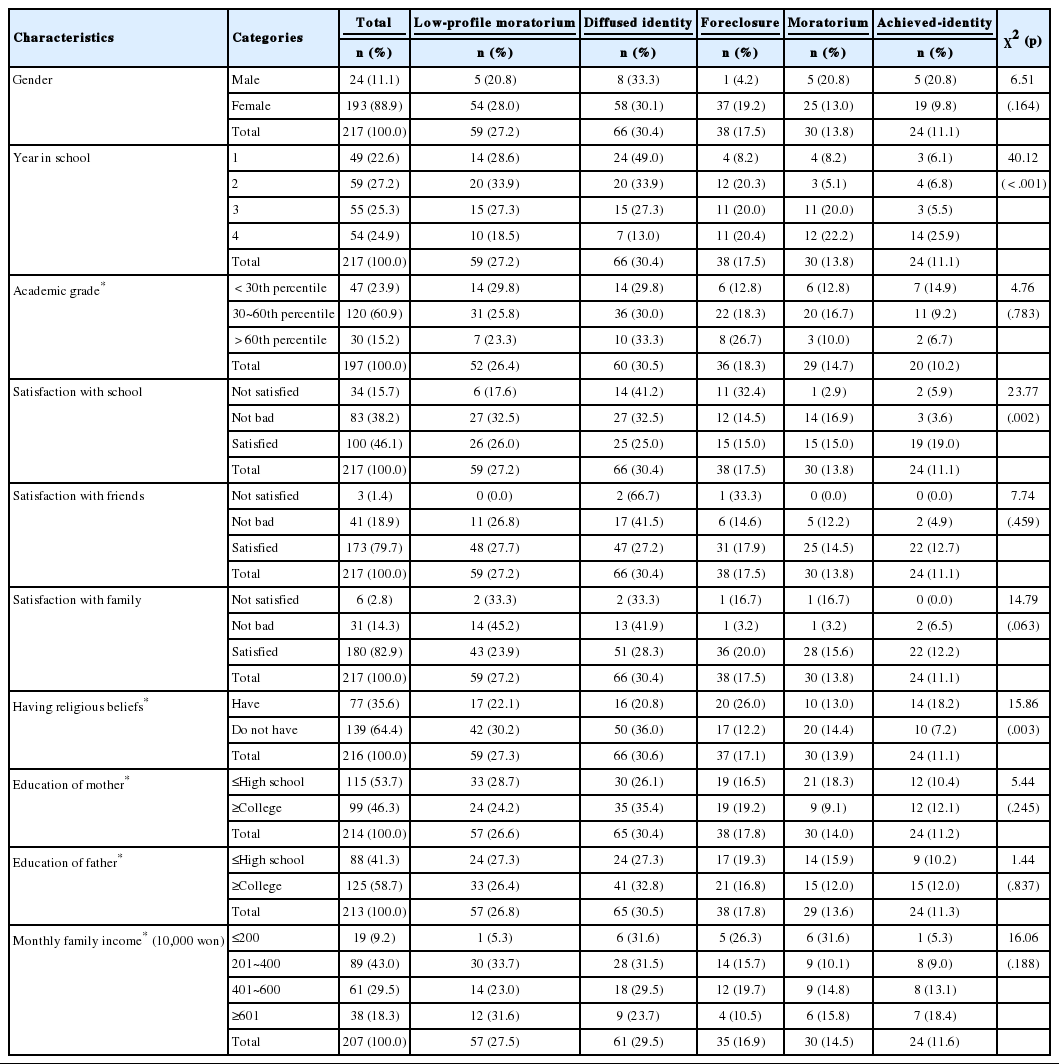

1. Demographic Characteristics and Ego Identity

The nursing students were 193 females and 24 males between 18 and 30 years of age (M=20.5, SD=1.9 years). And 22.6% were freshmen, 27.2% were sophomores, 25.3% were juniors, and 24.9% were seniors, while 60.9% of students answered being ranked between the 30th and 60th percentile. In addition, 46.1% of students reported being satisfied with school, 79.7% were satisfied with friends, and 82.9% were satisfied with family. Additionally, 35.6% of students professed a religion, and 46.3% of students’ mothers and 58.7% of students’ fathers had graduated from college. Forty-three percent of students’ families earned between 2,010,000 and 4,000,000 won monthly.

The means and standard deviations of the four dimensions (diffused identity, foreclosure, moratorium, and achieved identity) were 48.68±9.21, 37.61±9.58, 52.73±8.02, and 59.59 ±9.71, respectively. As well, cutoff points for diffused identity, foreclosure, moratorium, and achieved identity were computed at 53.29, 42.40, 56.74, and 64.45, respectively.

According to revised classification criteria [23], students were grouped into five ego identity statuses; 30.4% were diffused identity, 17.5% were foreclosure, 13.8% were moratorium, 11.1% were achieved identity, and 27.2% were low-profile moratorium.

2. Achievement motivation according to ego identity

Achievement motivation according to ego identity is presented in Table 1. Achievement motivation of students with moratorium and achieved identity was significantly higher than that of students with low-profile moratorium and diffused identity (F=9.58, p<.001). Particularly, both passion and hope dimensions among students with moratorium and achieved identity were higher than those of students with low-profile moratorium and diffused identity (F=9.27, p<.001; F=7.90, p<.001). In addition, the adventure dimension of students with moratorium and achieved identity was higher than that of students with low-profile moratorium (F=5.92, p<.001). Moreover, the self-confidence dimension of students with achieved identity was higher than that of students with low-profile moratorium and diffused identity (F=4.98, p=.001).

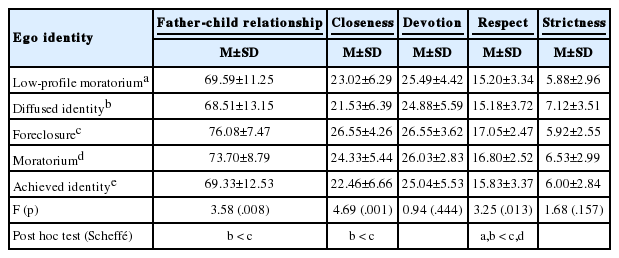

3. The parent-child relationship according to ego identity

The mother-child relationship according to ego identity is presented in Table 2. The mother-child relationship among students was not different according to ego identity, and dimensions of closeness, devotion, and strictness among students were not different according to ego identity. However, the respect dimension of students in foreclosure was higher than that of students with low-profile moratorium (F=3.11, p=.016).

The father-child relationship according to ego identity is presented in Table 3. The father-child relationship of students in foreclosure was significantly higher than that of students with diffused identity (F=3.58, p=.008). Specifically, the closeness dimension of students in foreclosure was higher than that of students with diffused identity (F=4.69, p=.001). Additionally, the respect dimension of students in foreclosure and moratorium was higher than that of students with low-profile moratorium and diffused identity (F=3.25, p=.013).

4. Relationship between ego identity and demographic characteristics

Relationship between ego identity and demographic characteristics are presented in Table 4. Ego identity of students was related to year in school, particularly, seniors were more with achieved identity, while freshmen and sophomores were more with low-profile moratorium and diffused identity (x2=40.12, p<.001). Ego identity of students was related to satisfaction with school, specifically, students who were satisfied with school were more with achieved identity, while students who were not satisfied were more in foreclosure and diffused identity (x2=23.77, p=.002). Ego identity of students was related to having religious beliefs, in particular, students who professed being religious were more in foreclosure, while students who did not were more with low-profile moratorium and diffused identity (x2=15.86, p=.003).

5. Factors influencing ego identity

To determine factors influencing ego identity of nursing students, multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed using the diffused identity as a standard dependent, while achievement motivation and the father-child relationship were included as covariates, and year in school, satisfaction with school, and having religious beliefs were inputted as factors.

Factors influencing ego identity are presented in Table 5. Factors influencing foreclosure compared to diffused identity were the father-child relationship (OR=1.09, p=.001) and year in school (freshmen) (OR=0.05, p<.001). Factors influencing moratorium compared to diffused identity were achievement motivation (OR=1.08, p=.001), the father-child relationship (OR=1.06, p=.043), year in school (freshmen) (OR=0.04, p<.001), and year in school (sophomores) (OR=0.08, p=.003). Factors influencing achieved identity compared to diffused identity were achievement motivation (OR=1.07, p=.003), year in school (freshmen) (OR=0.04, p<.001), year in school (sophomores) (OR=0.12, p=.010), year in school (juniors) (OR=0.12, p=.015), satisfaction with school (not bad) (OR=0.18, p=.027), and having religious beliefs (have)(OR=3.57, p=.032).

DISCUSSION

The proportions of achieved identity and moratorium in this study were 11.1% and 13.8%, respectively. These low ratios of achieved identity and moratorium were similar to 10.3 % and 13.0% in the study using the Korean version of EOMEIS II [22], as well 11.3% and 14.8% of a recent study using the same scale [6]. Less than a quarter of students were with achieved identity status and moratorium, which means that just a few students explored alternatives, while more than three quarters of students did not take risks to choose various options.

However, the proportions of diffused identity and low-profile moratorium in this study were 30.4% and 27.2%, respectively. These high ratios of diffused identity and low-profile moratorium were similar to 31.5% and 28.3% in the study of Korean students [6]. More than half of students were with diffused identity and low-profile moratorium statuses, which indicates that the greater part of students did not explore alternatives, moreover did not engage in any option. Many university students living in complex competitive societies don’t want to test alternatives nor commit to a decided option, but rather prefer to accomplish practical goals including earning certificates in certain skills and upgrading their academic scores [6].

This is because exploring alternatives in breadth and in depth has been known to be accompanied by stress [13]. Hence, individuals with moratorium feel chaotic and unstable while evaluating many options and opportunities [26]. However, individuals need to test new values and roles as well as engage in a decided option to achieve their own identities [12]. In other words, university students should submit to experiencing new tasks and responsibilities, at the same time, they should try to find answers for ego identity formation [5]. Therefore, nursing educators should support students to look at alternative beliefs and roles, and help them to test options during a stage of crisis. Specifically, guidance and counseling should be given to nursing students who are faced with struggles to explore various options and make decisions. In addition, systemic consideration and effective education programs are needed to encourage students to develop their ego identity.

As anticipated, ego identity of nursing students was related to achievement motivation. Achievement motivation among students with moratorium and achieved identity status was higher than that among students with low-profile moratorium and diffused identity status. It means that students who were deeply motivated to achieve tasks explored alternatives, and some of them reached the status of achieved identity through moratorium. Because achievement motivation stimulates students toward goal attainment and task fulfillment [18], highly motivated students could take risks of exploring new tasks, and finally could make decisions. In particular, the level of passion, hope, and self-confidence dimension among students with achieved identity status were higher than that of students with diffused identity status. In other words, nursing students could get out of diffused identity to reach achieved identity when they were devoted to doing work, hoped their desires would be realized, and believed in their own abilities.

The findings differed from an expectation that ego identity of nursing students was not related to the mother-child relationship. Nevertheless, the respect dimension in the mother-child relationship of students in foreclosure was higher than that of students with low-profile moratorium status. As well, the father-child relationship of students with achieved identity status was not different from students with other statuses; rather, the father-child relationship of students in foreclosure was higher than that of students with diffused identity status. It indicates that students who highly regarded their parents tended to accept the values of their parents.

Parental support did not affect much more in the time from adolescence to early adulthood than before [27]. It is known that late adolescents’ relationships with their parents become more bidirectional than early adolescents’ relationships [14]. Thus, nursing educators should consider the changing process of the parent-child relationship in students, and help them to alter dependent relationship into interdependent relationship.

As expected, seniors were more with achieved identity status, while freshmen and sophomores were more with diffused identity status, which was similar to the findings of the study in Korean nursing students [6]. It has been insisted that the number of individuals with diffused identity and foreclosure statuses decrease, though the number of individuals with achieved identity status increase over time [4,12]. Therefore, this study verified the progression to achieved identity from diffused identity.

Along the same lines, students unsatisfied with school were more in foreclosure and diffused identity statuses. Nursing students share their values and beliefs with peer students, as well, construct their identities during educational process [1]. Consequently, students need to be supported to adapt to their university lives, and at the same time, to have enough experiences to be involved in diverse university activities.

Additionally, students who professed a religion were more in foreclosure. Ego identity was supposed to be related to having religious beliefs, because individuals in foreclosure accept the opinions and values of authorities, including religious doctrines or religious leaders [12].

Factors influencing achieved identity compared to diffused identity were achievement motivation, year in school, satisfaction with school, and having religious beliefs. As anticipated, nursing students reached the status of achieved identity when highly motivated to accomplish tasks. Strongly motivated students are those who trust in their capability for work, and take risks in the expectation of good results [19]. Every student might have a different level of achievement motivation because of different experiences [28]. Considering that students can learn their capabilities through experiencing accomplishments and failures [28], nursing educators should encourage students to experience success and failure, and guide them to learn lessons.

In this study, an interesting point to note was that the father-child relationship was the factor influencing moratorium and foreclosure compared to diffused identity, but it did not influence achieved identity. It was supposed that parental support did not give the effect so much during the transitional period from adolescence to adulthood [27]. Accordingly, it is recommended that parents should try to change their parental roles from direct protection to secondary support when children’s desire for independence and autonomy increase [29]. Above all, this study revealed that achievement motivation of students influenced attainment of ego identity more than did the parent-child relationship. Furthermore, these findings supported the results of a previous study [16] that students who had strong intrinsic motivation to accomplish desired goals could attain their identities despite poor family relations.

As expected, year in school and satisfaction with school were related to achieved identity. Ego identity progressed from diffused identity to achieved identity through foreclosure and moratorium over time [26]; therefore, seniors were more with achieved identity status, while freshmen were more with diffused identity status. Nursing students share their opinions with peers, and observe occupational roles of nurses during educational programs [1]. Especially, clinical training is essential for nursing students to form their identities as nurses [30]. Owing to this reason, seniors who more experienced learning contexts and clinical practices had more chances to achieve their identities. In the same vein, students who were satisfied with their university lives could progress in achieved identity.

In addition, having religious beliefs was related to achieved identity. Ego identity is composed of occupation and ideology areas including having a religion [7]. For this reason, an individual who professed a religion experienced a process of thinking and choosing alternative values or beliefs, and finally decided to commit to a preferred value.

This study emphasizes that ego identity of Korean nursing students is more affected by achievement motivation than by the parent-child relationship. It indicates that students deeply motivated to attain tasks could achieve their ego identities regardless of the parent-child relationship. Moreover, it means that personal intrinsic factors, for example achievement motivation, are more important to develop ego identity than are extrinsic environmental factors, including the parent-child relationship.

In this study, a causal relationship was not derived because of the cross-sectional descriptive study design. Additionally, generalization of these findings may be limited because of convenience sampling. Furthermore, all the factors that could influence ego identity were not included. Regarding these limitations, future research should consider longitudinal study design to identify the causality between identity achievement and related factors. Also, further research needs to be done using random sampling, and should include other factors such as personality type, communication skill, and relationship with significant others.

CONCLUSION

This study was conducted to characterize the influence of achievement motivation and the parent-child relationship on ego identity in Korean nursing students. In this study, factors influencing achieved identity compared to diffused identity were achievement motivation, year in school, satisfaction with school, and having religious beliefs. The results revealed that the achievement motivation of nursing students influenced ego identity attainment more than the parent-child relationship. Nurse educators should support students to progress in ego identity attainment and develop a procedure to improve the achievement motivation of students.

Notes

No potential or any existing conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.